Former President Barack Obama said during an episode of a podcast released on Dec. 17 that he believes college athletes should be paid.

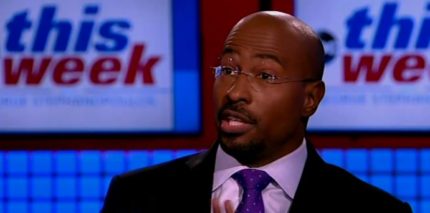

On an episode of “The Bill Simmons Podcast” with host Bill Simmons and CNN political analyst Bakari Sellers, Obama expressed support for the proposition that college athletes should be able to earn money from their on-field exploits.

When Sellers asked Obama if he believed college athletes should be paid, the 44th president expressed his support for the idea.

“Yes. I think that the amount of money that is being made at the college level, the risks that, let’s say, college football players are being subjected to, and the fact that for many of these colleges, what these young people are doing are subsidizing athletic director salaries, coach salaries. All of that argues for a better economic arrangement for them, and I think there is a way of doing that that doesn’t completely eliminate the traditions and the love we all have for college sports.”

A 61-page legislation called the “College Athletes Bill of Rights” concerned with college athletes’ ability to make money from their names and image was introduced by Democrat in the Senate last week.

“The bill is the result of growing outrage with a failure to protect athletes’ health and safety and treat them fairly financially,” Sen. Richard Blumenthal told USA TODAY Sports. “Literal blood, sweat and tears of athletes have fueled a $14 billion industry with very little benefit to them — and a lot of harm.”

The NCAA Board of Governors said in April that it was supportive of rule changes that would enable athletes to receive compensation from third-party endorsements related and unrelated to athletics. Student-athletes would not be permitted to use school or conference logos in advertisements.

However, the NCAA is set to argue before the Supreme Court in 2021 that athletes’ education-related compensation should be limited. The high court has agreed for the first time since 1984 to rule on a case involving the NCAA by reviewing a lower court’s ruling in an antitrust case. The NCAA claims the lower court’s decision in the case blurs “the line between student-athletes and professionals,” by removing caps on the amount of education-related compensation college athletes can receive.

The 9th U.S. Circuit Court ruled in May in a case brought by former West Virginia football player Shawne Alston and others that the NCAA could not cap that king of compensation for student athletes in Division I football and men’s and women’s basketball programs.

The NCAA, in its appeal to the high court, has characterized that ruling as “blurring the traditional line between college and professional athletes,” but the players’ attorneys say that’s an exaggeration. The ruling apples “only to NCAA restrictions on education-related benefits that schools may offer Division I basketball and FBS football players benefits such as computers, science equipment, musical instruments, postgraduate scholarships, tutoring, study abroad, academic awards, and internships,” and does not amount to “so-called pay for play.”

A decision from the Supreme Court is expected by the end of June.

Collegiate football and basketball generate upwards of $1 billion for the NCAA each year, and top coaches are often paid seven-figure salaries.

“The whole myth of student-athletes really evolved in part because early on football players who are being brought in as ringers on these teams were getting hurt and then suing for workers’ comp and suddenly the colleges figured out if we form this association and create this ideal of student-athletes that we’ll protect our pocketbooks,” Obama said on the podcast, which was recorded in late November. “So, yes, we should make some changes there.”

In 2018, 56 percent of Division I men’s college basketball players and 48 percent of football student-athletes were Black, according to the NCAA.