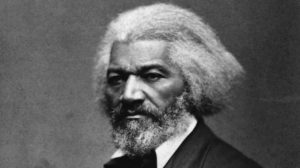

Abolitionist and escaped slave Frederick Douglass died in 1895.

During a week when the president’s new immigration restrictions incited global protests and condemnation, Donald Trump attempted to demonstrate a moment of nuance and inclusion. FOX 32 Chicago reported the president christened “February 2017 as National African American History Month.” After consorting with “respectable” African-Americans, President Trump “came to a consensus that the term ‘Black’ was outdated and that the more appropriate way to refer to the community was ‘African American.'” The new president milked every Kumbaya-drop of the commencement, declaring the White House bust of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. “one of [his] favorite things” and awkwardly praising abolitionist Frederick Douglass. Trump stated, “Frederick Douglass is an example of somebody who’s done an amazing job that is being recognized more and more, I notice.” Speaking as if Douglass were alive and able to help make 2017 America great again.

This incident parallels many productions of Black History Month: Brief, superficial and a colossal affront to generations of Black genius, suffering and scholarship. Dr. Tommy J. Curry, a Texas A&M University professor and author of “The Man-Not: Race, Class, Gender and the Dilemmas of Black Manhood,” often highlights the predictably inadequate February homages to Black achievement. In an interview with Atlanta Black Star, Curry details Carter G. Woodson’s motivation for establishing the recognition of Black history, which began as a week, not a month. Curry says Woodson “intended to solidify the Negro’s future through his understanding the lessons of the past.” A historian and author of “The Mis-Education of the Negro,” Woodson warned, “If a race has no history, if it has no worthwhile tradition, it becomes a negligible factor in the thought of the world and it stands in danger of being exterminated.” Curry stresses that instead of Woodson’s “Black History Month being a glorification of Blacks within America’s empire, it was meant to be the curricula by which Black Americans could cultivate Black civilization.”

Diminishing the accomplishments and breadth of Black ancestors deliberately malnourishes Black futures. Atlanta Black Star asked Curry to explain the problem with February’s slender emphasis on minuscule portions of the legacies of Dr. King and Montgomery, Alabama, bus boycott leader Rosa Parks. He described how this focus “unjustifiably emphasizes the peaceful protests and Christian ethos of the civil rights movement over the persistent struggles everyday Black communities undertook against white supremacy.” World War II veteran and NAACP leader Medgar Evers and Jimmie Lee Jackson, whose death was dramatized in Ava DuVernay’s “Selma” and countless other Black people sacrificed their lives to end racism. Professor Curry reminds us that King, Evers and Jackson were “targeted by the racist state apparatus which was often concealed locally.” Draconian surveillance and government-sanctioned repression were designed to ensure that large numbers of petrified Black people were willing to comply with white power.

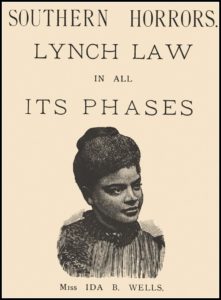

Woodson’s vision of Black history would mandate a vigorous accounting of the enormity of Black resistance. Clichéd Black history presentations, in professor Curry’s view, substantiate the fairy tale that most Black thinkers and activists “believed that integration was and is the best option Blacks have to pursue,” a view staunchly rejected by journalist and anti-lynching crusader Ida B. Wells-Barnett. Curry, who’s written about the iconic freedom fighter, says Wells-Barnett concluded whites were irredeemably devoted to racism and their lynch mobs “could only be stopped by armed self-defense.”

“Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases,” was published by Ida. B. Wells-Barnett in 1892.

In “Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases,” Wells-Barnett makes it plain: “A Winchester rifle should have a place of honor in every black home, and it should be used for that protection which the law refuses to give. When the white man who is always the aggressor knows he runs as great a risk of biting the dust every time his Afro-American victim does, he will have greater respect for Afro-American life. The more the Afro-American yields and cringes and begs, the more he has to do so, the more he is insulted, outraged and lynched.”

Curry charges that Woodson’s vision of Black history would proudly feature Black ministers of self-defense like Wells-Barnett and North Carolina’s Robert F. and Mabel Williams, who headed their local NAACP chapter and wrote “Negroes With Guns.” By redacting Black arms, Curry argues that Woodson’s project is castrated by exclusively exhibiting “a peaceful caricature of Dr. King to socialize Black Americans into believing that peaceful protest, respect for the law and faith in this country are their only alternatives to white racism and the continuing growth of white supremacy.”

“Most Black thinkers never believed white Americans or this society would ever truly include them,” Curry concludes. “To reduce Black History to the ideology of integration is to make the centuries-long struggles of Black people synonymous to the empty rhetoric of a white society committed to the prolonged subjugation of Black people.”

In fact, President Trump’s beloved Frederick Douglass made a number of remarks typically omitted from the February shindigs. On the eve of the Civil War, Douglass stated, “I have little hope of the freedom of the slave by peaceful means. A long course of peaceful slaveholding has placed the slaveholder beyond the reach of moral and humane considerations. … The only penetrable point of a tyrant is the fear of death.” It’s difficult to imagine Trump encouraging his African-American constituents to resurrect Douglass’ unwavering commitment to justice and conquering of tyrants.