People of color are being fleeced by law enforcement and the criminal justice system. The public began to pay more attention to the practice in places such as Ferguson, Missouri, where the courts and police preyed upon Black residents through court fines and fees. The exploitative system became a substantial revenue generator for the municipality, and a major source of anger for the poor, Black residents of the city who were targeted for racial profiling stops by police. Now, the latest scandal is that of civil asset forfeiture in Oklahoma.

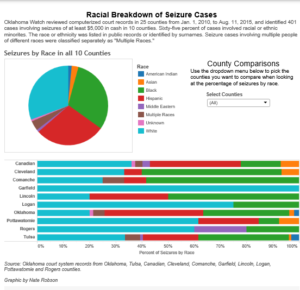

Almost two-thirds of cash seizures by police in Oklahoma come from Blacks, Latinos and other racial and ethnic groups, according to a report from Oklahoma Watch. The analysis of big-dollar forfeiture cases in 10 Oklahoma counties demonstrates that law enforcement relies on racial profiling, even if subconsciously, to determine which vehicles to search and whose money to seize.

The study used court records to analyze forfeiture cases involving seizures of at least $5,000 in cash between 2010 and 2015. Out of the 401 cases, 65 percent involved Hispanics, Blacks, American Indians, Asians or other minorities. Blacks were represented the most, with 31 percent of cases, and Latinos with 29 percent. In Oklahoma County, three-quarters of cases involved people of color, including 38 percent involving Latinos, and 33 percent involving Blacks. In addition, in Tulsa County, Blacks comprised 35 percent of forfeiture cases, and Hispanics comprised 21 percent. Whites were merely over a third of such cases.

However, Oklahoma County Assistant District Attorney Scott Rowland denied that people of color are the targets of forfeitures, arguing, “I don’t believe these officers are racially profiling. Number one, it’s illegal, it’s unconstitutional. And number two, frankly, I don’t think it’s effective.”

The scale of the problem of civil asset forfeitures is national, as the U.S. Sentencing Commission has found that 80 percent of those convicted of drug trafficking in federal court are racial and ethnic minorities. While law enforcement will deny they are racially profiling people, and claim that this is because Latinos are targeted by Mexican drug cartels, civil liberties and advocacy groups are drawing attention to the practice, which they say allows police to take citizens’ property without a charge or conviction, thereby violating their civil rights.

According to the ACLU, the abuse of civil asset forfeiture laws—which allow police to seize, keep and sell any property they allege is involved in a crime, “has shaken has shaken our nation’s conscience.” Further, a person need not ever be arrested or convicted for their vehicle, cash or even house to be seized by the government, never to be seen again, as reclaiming such property is notoriously difficult and expensive, with costs sometimes exceeding the value of the property itself.

“Forfeiture was originally presented as a way to cripple large-scale criminal enterprises by diverting their resources,” the organization says on its website. “But today, aided by deeply flawed federal and state laws, many police departments use forfeiture to benefit their bottom lines, making seizures motivated by profit rather than crime-fighting.”

In September 2014, the Washington Post shed light on the scale of this policing for profit scheme. According to the Post report, following 9/11, local police, county deputies and state troopers, with millions of dollars in training from the departments of Homeland Security and Justice, were encouraged to more aggressively search for drugs, contraband and suspicious people. This fact has led to the growth of an aggressive type of policing that has resulted in the seizure of hundreds of millions of dollars from thousands of motorists and others who were charged with no crimes.

“A thriving subculture of road officers on the network now competes to see who can seize the most cash and contraband, describing their exploits in the network’s chat rooms and sharing ‘trophy shots’ of money and drugs,” the report revealed.

Some police promote the concept of highway interdiction as a means of generating revenue for cash-strapped municipalities. Nationwide, law enforcement agencies routinely purchase vehicles and weapons with this seized cash.

Moreover, a barely known cottage industry has developed in which private police-training firms teach the techniques of “highway interdiction” to police departments across the country. One of these firms, Black Asphalt Electronic Networking & Notification System, created a private intelligence network that allowed police to share detailed reports on motorists nationwide, including social security information, addresses, identifying tattoos and suggestions on which people to stop.

These abusive techniques have a disproportionate impact on Blacks, Latinos and others. In 2012, the Philadelphia City Paper made a parallel between civil asset forfeiture and the controversial “stop-and-frisk” policy, given that both target young Black and Latino men.

“Call it ‘stop and seize,’ a legal dragnet that catches the innocent, guilty and unaccused alike,” the City Paper wrote.