More than 160 years after being denied the opportunity to practice law in Maryland, a campaign has been launched to get one Black man admitted to the Old Line State’s bar.

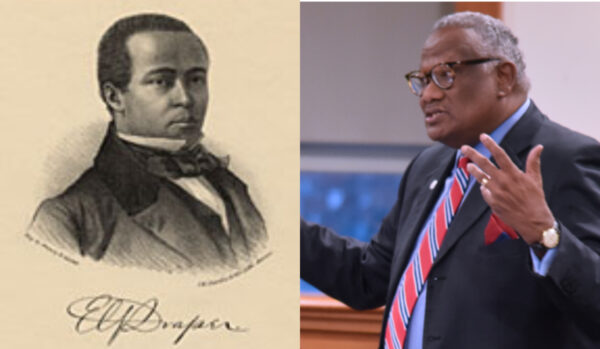

Thanks to several attorneys familiar with his story, Edward Garrison Draper’s legacy will no longer have an asterisk next to it.

On Thursday, Feb. 16, a panel of scholars and historians gathered at the University of Baltimore to discuss Draper and how race and slavery stopped him from being the first Black man to be a lawyer in the state of Maryland.

Led by José F. Anderson, the Dean Joseph Curtis Professor of Law at the University of Baltimore School of Law, the symposium featured historian, Texas lawyer, and retired justice John G. Browning and Maryland attorney Domonique Flowers. They believe that they can develop a strategy to right the great wrong that kept Draper from practicing law in the United States.

Browning, who has been researching Draper’s life for years, said, “Justice doesn’t have an expiration date,” according to the Daily Record, and has joined Flowers in his effort to have the man posthumously admitted to the bar and recognized as a lawyer in the state.

Draper’s qualifications are vast, all three scholars noted, with Browning sharing that although Draper was amply qualified, Superior Court Judge Zachaeus Collins Lee, a first cousin of Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee, concluded that the Black man was not a “free white citizen of this state,” and he could not gain entry to the bar.

Lee actually conducted Draper’s oral exam and issued him a certificate establishing his qualifications so that Draper could practice elsewhere — in Liberia, where many emancipated or free Black Americans emigrated in the mid-1800s. Draper, a Dartmouth graduate, succumbed to tuberculosis on Dec. 18, 1858, after living in Africa for one year.

Anderson, in an exclusive interview with Atlanta Black Star, spoke about the petition to have Draper recognized as a lawyer in the United States.

“A group of lawyers, led by Maryland Attorney and legal historian Dominique Flowers, is planning to file a petition to the Maryland Supreme Court to grant Draper Posthumous admission to the Maryland Bar,” he told Atlanta Black Star.

The dean shared details about Draper’s extraordinary life and how race and racism played a part in impeding his domestic success.

Draper was the only child of a free Black business owner in Baltimore and received his degree from the New Hampshire Ivy League 10 years before the 13th Amendment abolished slavery in the United States, Anderson shared.

“At this juncture in American history, only a handful of Black Americans had become lawyers, beginning with Macon Bolling Allen in 1844. In those days, Maryland (like most states) did not require a college degree or law school education for admission to the bar, and there was no formal bar examination,” the professor added.

To be a lawyer in Maryland at the time, he shared, one only had to be over 21, “a citizen of Maryland, of good moral character, and had to have engaged in the study of law for at least two years – usually by ‘reading the law’ under the tutelage of an older lawyer or judge.”

Draper was 24 years old when he presented himself before Lee. He had apprenticed and studied for more than two years under respected Baltimore lawyer Charles Gilman and “spent several months in Boston with prominent attorney Charles Storey observing courtroom proceedings.”

Lee remarked at the young African-American’s brilliance, saying he was “most intelligent and well informed in his answers to the questions proposed by me, and qualified in all respect to be admitted to the bar in Maryland if he was a free white citizen of this state.”

The group of lawyers is currently exploring the appropriate way to present this petition to the court, examining the best legal path to a successful resolution. Members of the collective have also researched precedent cases of posthumously elevating legal minds and professionals to the status of lawyers.

According to Browning, the United States has granted six other attorneys posthumous bar admissions. Of the six, three were Asian Americans who were also denied admission to their state bars (California and Washington) because of their race. The other three have been Black, in Pennsylvania, New York, and Texas. Those men have different circumstances than Draper. The courts later found that each was wrongfully barred from practicing law but had once been lawyers.

“We hope the petition will be well received and that Maryland’s highest court will help in righting a historic wrong,” Browning said in an email.

As of now, the lawyers are caucusing and working out a plan, though most of their argument is already collected and with the history in hand and precedent met, Anderson believes there is a strong chance the history books will be changed.