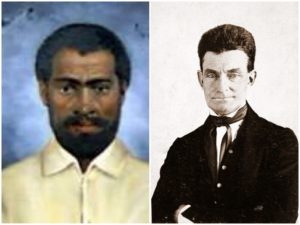

Nat Turner and John Brown (Wikipedia Commons)

During a 2011 interview, funnyman, author and civil rights activist Dick Gregory vehemently rejected a comparison between John Brown and Nat Turner, a pair of 19th-century rebels who killed and died to end slavery.

“John Brown was a white man,” said Gregory. Emphasizing that Brown had nothing to gain, yet forfeited both he and his children’s lives in their failed 1859 raid on Virginia’s Harper’s Ferry, Gregory asked rhetorically, “Do you know what Harriet Tubman said on her deathbed? ‘My only regret in life [is] that I wasn’t there to die with John Brown.'”

Dick Gregory and generations of Black people have been inundated with hymns and propaganda praising Brown or any white person who’s alleged to have lent a hand to end racism. Frequently, these helpful whites garner greater attention than the Harriet Tubmans, Nat Turners and thousands of Black counter-terrorists who invested their complete existence in Black liberation.

W.E.B. DuBois, historian, sociologist and co-founder of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, wrote a biography in reverence to Brown. In the introduction to the 2010 edition, historian David Roediger explains how DuBois’s original subject was Virginia freedom fighter Nat Turner, but whites “refused approval of the Turner biography.” A Black patriot demanding liberty or death could not be lionized.

This orchestrated and disproportionate focus on the handful of John Browns (who actually set a high bar for white anti-racist by organizing armed resistance against the enslavement of Black people) is designed to promote Black glorification of and immense gratitude for “good white people.” From Brown to contemporary “woke” whites who name-call President Trump or name drop (insert popular Black author), appreciation for white allies exponentially exceeds white will to permanently eradicate Black suffering.

“They came with their bright ideas, but they also came with their racism,” said Lorne Cress Love when asked to describe the 1964 whites who spent their summer interning for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee’s Mississippi Campaign. Cress Love, who volunteered for SNCC, remembers how white students “were greeted by Black people who were so glad to see a white person who was not kicking their butts that they just adored these white people.”

Emphasizing that a half-century has not weakened these memories, Cress Love remembers the conclusion of a SNCC meeting where a Black preacher prayed unequally for the white and Black volunteers. “This minister [thanked] God for these wonderful white people who have come down here to help us. And I really got incensed,” Cress Love said.

Providing context for her remarks, she underscores that in 1960s Mississippi, Black SNCC volunteers and apolitical citizens alike were victims of terrorism. As a result of decades of economic plunder, Cress Love and other Black activists were financially deprived in comparison to their white counterparts. Responding to the minister’s special prayer for the “wonderful whites,” Cress Love stated, “They made a little sacrifice, but he could not see the sacrifices that Black people were making.”

Victims of racism typically overestimate both white commitment to justice and the bravery of so-called white allies. Rev. James Reeb and Viola Liuzzo are common references for the mortal danger confronting whites who reject their duties to white supremacy. In 1965, both made fatal pilgrimages to Alabama to aid Black civil rights campaigns. Ava DuVernay’s acclaimed film “Selma” includes Liuzzo and the graphic murder of Rev. Reeb.

Even though whites who’ve traded their lives to stop racism are as rare, these aberrations are used to evidence the astounding risk taken and courage demanded of so-called white allies.

Educator and activist Jane Elliot scolds this notion. The creator of the celebrated blue eyes/brown eyes exercise, which helps demonstrate how racism works, Elliot admits to being racist and being groomed from childhood to carry out racism. During a 2010 interview, she revealed that because of her critiques of whites, she’s been assaulted and had her life and the lives of her children threatened. After all that, she declared emphatically, “It doesn’t take courage to do what I do.” With candor, Elliot explained that no one demonstrates more bravery than Black people who rise daily to endure and oppose racial terrorism.

Fellow white activist Mab Segrest uses her autobiography to warn readers that even whites who devote years to an armed interracial crusade can easily relapse, return to being white. In “Memoir of a Race Traitor,” Segrest details the life of post-Civil War Georgia politician Tom Watson. A leading figure in radical politics at the end of the 19th century, Watson campaigned openly against racism at a time when public castration and lynching of Black people was routine. Watson’s Georgia compatriots denounced lynching and rallied arms to stop a fellow Black party member from being hung.

But interracial harmony proved too challenging. In less than a decade, Watson reneged on his commitment to brotherhood and, writes Segrest, “turned racist and campaigned in 1906 on … a platform of ‘Negrophobia.’”

Loosely translated, “Negrophobia” means “Black people are scary; don’t help them.”

And most often, whites collectively don’t.

Most whites didn’t help end the enslavement of Black people. Most whites didn’t help Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. march. Most white voters didn’t help Barack Obama win either presidential election. John Brown and Jane Elliot are infrequent anomalies that obscure the common and enduring white devotion to ‘Negrophobia.”

In a 2010 interview, Rhodes College professor Zachary Casey explained that, “The need for good white people is felt by both white people and people of color.” Casey branded this “white lie” an obstruction to justice, saying, “This idea that it’s ‘not all white people’ … prevents us from actually dismantling” white supremacy. Searching for and highlighting whites who’ve authentically assisted Black people flagrantly obscures collective and consistent white opposition to Black independence and progress.

Casey’s assessment echoes the diagnosis of late author and psychologist Bobby E. Wright: “The greatest pathology in the world is for people to believe in something just because they wish it to be so.”

—————————————————————————————————

Gus T. Renegade hosts “The Context of White Supremacy” radio program, a platform designed to dissect and counter racism. For nearly a decade, he has interviewed and studied authors, filmmakers and scholars from around the globe.