Congregation with their pastors at a revival. Getty Images

The church has always played a significant role in the history of Black people. It has been both a pacifier of Black struggle and a leader in resisting racism. Twenty-four hours after confessed white supremacist and convicted mass killer Dylann Roof slaughtered nine Black worshipers in Charleston, South Carolina’s historic Mother Emmanuel AME Church, general and child psychiatrist Dr. Frances Cress Welsing accurately predicted the events in the next day’s court proceedings, where grieving relatives of the Emanuel 9 extended Christian-prescribed forgiveness to the radicalized white man who desecrated their sanctuary and murdered their loved ones. Many Black people saw the pardoning of a racist ambush as the latest illustration of Christianity’s everlasting damage to Black people.

On the other hand, founder and senior pastor of Philadelphia’s Epiphany Fellowship Dr. Eric Mason insists, “Black Christian churches have provided unparalleled nourishment for Black people. And, in many instances, these houses of worship have been the vanguard of Black rebellion.”

There’s much to substantiate his claim.

Black people have used the church to serve our spiritual craving for justice. In “Black Religion and Black Radicalism,” Gayraud Wilmore shares the observations of a 1722 enslaver in colonial North America. “Sunday was a favorite day on which the slaves often planned outbreaks, because it was easy to get together on Sunday,” which, the colonizer continues, led many plantation owners to conclude “religious services were the great incubators where slave insurrections were hatched.” White slave owners were became so wary of “their property” using Christian teachings to foment uprisings moved to decree that all religious practice, aside from individual prayer, would now be allowed.

Former President Barack Obama highlighted this tradition of Black Christian insurrection during his 2015 eulogy for Rev. Clementa Pinckney, a former state senator and pastor of Mother Emmanuel before being assassinated by Roof. The first Black president listed how Black churches served as “rest stops for the weary along the Underground Railroad; bunkers for the foot soldiers of the Civil Rights Movement.”

The Black civil rights movement of the 1950s and ’60s, which served as counter-terrorism campaigns, lived in Black Christian churches. The late Coretta Scott King describes church as “an escape and a sanctuary” from the daily onslaught of racism, which includes the assassination of her husband, a Black Christian minister. The pooling of resources, networking and organizational structure of Black places of worship allowed for sustained attacks like the 1950s Montgomery Bus Boycott, shepherded by King and Rosa Parks, both Christians.

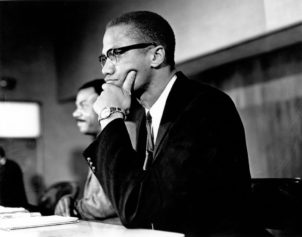

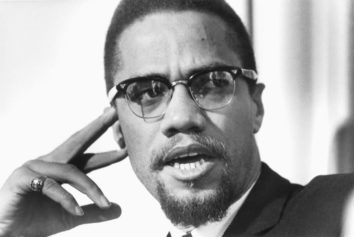

Although not as well known as Parks and King, Black ministers like Detroit’s Bishop Albert Cleage and Harlem’s Adam Clayton Powell Jr. were equally committed to Black spiritual and political self-determination. Incubated during the civil rights era, Cleage’s Shrine of the Black Madonna was founded explicitly to combat racism. Influencing Detroit politics for decades, Cleage demonstrated practical political application of his Sunday sermons. Rev. Powell did the same in Harlem. Splitting time between the Abyssinian Baptist Church pulpit and the U.S. House of Representatives, the Black Christian congressman hobnobbed openly with Malcolm X and invested much of his life challenging the political repression of Black people.

Mason accepts criticism that current ministries have strayed from this history of Christian activism. He concedes that, despite the reputation of “megachurches,” many congregations have dwindled in number over the past 50 years, which has syphoned their political vitality. The Black youths who were frequently the frontline of civil rights boycotts and sit-ins are often absent from Sunday pews. These are legitimate concerns about the 21st-century longevity and relevance of Black Christian ministries.

But, even this has not stopped multitudes of churches from continuing their mission to serve Black spiritual and practical needs. Mason cites the 2016 Alfred Street Baptist Church college festival in Virginia, which awarded $2.1 million in scholarships to students attending historically Black colleges and universities. For 15 years, the church has organized this festival to reaffirm its commitment to Black academic empowerment. In March of this year, Chicago’s Harztell Memorial United Methodist Church hosted seminars on the health impacts of racism on Black families. Like generations of Black churches, they make time to examine the mechanics of racism and how their ministry can help solve the problem.

Acknowledging that religion has been used to promote “violence, death and destruction, and systemic institutional racism,” Mason asks us to think of Christianity as a tool, like a knife or medication, which can promote harm or healing. He submits that Black Christian soldiers have a healthy body of work to reflect their contribution and commitment to Black liberation.

There’s a reason white terrorists like Dylann Roof continue to target Black sanctuaries. These places of worship have an indisputable record of galvanizing Black masses to fight against white supremacy. This tradition can be resurrected.

Gus T. Renegade hosts “The Context of White Supremacy” radio program, a platform designed to dissect and counter racism. For nearly a decade, he has interviewed and studied authors, filmmakers and scholars from around the globe.