The last couple of years has created a renewed, more mainstream sense of activism, as Blacks have pulled conversations around race relations, Black lives and systemic racism up the national flagpole, at times provoking conversations in public spaces that haven’t made American society this uncomfortable since the civil rights era. Naturally, there are comparisons between today’s #BlackLivesMatter movement and the civil rights movement, as both have been periods where a congregation of Blacks have thrust racial injustice into the face of the nation via walkouts, marches, speeches and boycotts. As today’s movement continues, it’s unclear who is leading it — or if that matters — but it’s clear that the struggle around rights and resistance to injustice has reached levels not seen since the 1960s in all areas of Black life.

One such realm in resistance has been in sports. In the NFL, these public demonstrations have perhaps been the most persistent; several St. Louis Rams players displayed the “hands up, don’t shoot” gesture popularized coming out of the Ferguson protests, and after a Black Panther-styled Super Bowl halftime show performance by Beyonce’, the league had to contend with the sustained protest embodied by San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick.

In the NBA, the players took a more subdued approach to political commentary on Black lives, with players donning “I Can’t Breath” T-shirts and delivering balanced messages. One such message was given by James, Carmelo Anthony, Chris Paul and Dwyane Wade at last year’s ESPY Awards. The group called for both an end to the killings (“The shoot-to-kill mentality has to stop. Not seeing the value of Black and brown bodies has to stop.”) and also an “NBA Cares” style call to action to their peers (“Let’s use this moment … to educate ourselves, explore these issues … and most importantly, go back to our communities and … help rebuild them.”) that made it clear that they didn’t see the issue as one-sided.

James and company got lauded, and in some corners, criticized, for their comments. Yet, in many ways, a more uncompromising campaign was being waged during the same period by the WNBA, where nearly half the league engaged in public protest to the repeated injustices of systemic racism. Their actions raised the stakes for themselves while raising awareness with their platform; while the league charged teams and players $5000 and $500, respectively, for players wearing Black Lives Matter-themed shirts, the players engaged in a media blackout, holding the line on only answering media questions if the players were asked about the recent police-related murders. The back and forth with the league and the media lasted a significant part of July, eventually not only garnering media awareness but also support from the league; the fines were eventually rescinded and the league president issued a statement of support for the players.

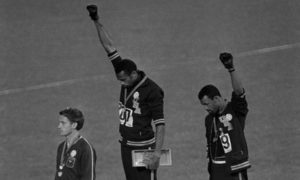

Athletes who protested against racism put their lives and careers in jeopardy. There is the much-told story of Muhammad Ali, who, in 1967, was stripped of his title and his license to box for protesting the Vietnam War. Ali famously stated, “I ain’t got no quarrel with those Viet Cong.” Ali was convicted of draft evasion and sentenced to five years in prison. (He was not imprisoned during that time as his case was being appealed). He was banned for three years and fined $10,000. There are lessor-known stories like John Carlos’, one of the two men who gave the Black Power salute on the medal podium at the 1968 Olympics. Carlos, who won the bronze medal in the 200-meter race — Tommie Smith won the gold — faced a difficult time for nearly a decade after the protest he said “cost him everything.” Loss of his reputation as he was pummeled in the press, a struggle to find work, his children harassed in school, FBI surveillance, and the eventual suicide of his wife. By the late ’70s, however, Carlos was able to recover and lead a good life as a drug counselor. Today’s athletes risk and endure far less than those who came before them, yet their activism pales in comparison.

The everyday citizen has used public stages, too, with varying levels of sacrifice and impact. Shortly after the Ferguson protests, in Oakland and New York City, Black demonstrators interrupted brunches in white-dominant places, reciting the names of victims for four-and-half minutes. In Boston, a dozen Black Lives Matter protesters clogged I-93 by chaining themselves together.

Yet and still, there continues to be a question of what protest and resistance should look like in the early era of Trump. Much of today’s activism has been seen as — and reduced to — “click-activism.” Resistance most appealingly taking the form of social media branding by a rising Black generational base that feels stylistically at odds with the “boots on the ground” resistance of the old days. It’s been hard for many to embrace this new approach, which seems more amassed in media profile pieces, Twitter retweets and Instagram hearts, and less intent on disrupting spaces and cultivating a bench of leadership. For this generation though, there’s also a healthy skepticism about the approaches of old; heavily steeped in a pulpit-style, straight male-dominated, respectability vein that feels outdated today. Where does the answer to move forward come from?

Likely still from the past, and in that regard, the Montgomery bus boycott holds some of the best ideas about how to maintain resistance in this new era. As a 381-day campaign for change that encompassed 40,000 people and held a nation in sway, the boycott is still one of the crowning moments of Black resistance and organizing against American racism in Black history. The ground game on this boycott was strong and coordinated, and in a world where resistance and defiance have come to mean removing your ride-sharing app, its a measure of how far we have drifted in our activism. Seventy-five percent of the city’s bus ridership was Black, but the community accommodated and anticipated that inconvenience. Black taxi drivers severely reduced their fare to 10 cents and carpools coordinated by groups and churches made sure no ground was given.

It resulted in the banishment of bus segregation, a greater investment in hiring Black bus drivers and making something as simple as taking a bus ride more humane. Instead of Blacks being forced to give up their seats to white riders and move to the back of the bus, it instead helped institute” first come, first serve,” a practice so rudimentary that it’s insane to think it had to be litigated.

In her “Good Morning America” interview days after being arrested, Newsome said, “I felt very strongly we needed that moment. We needed that moment to say, ‘Enough is enough. We want an end to the hate.’” It continues to be a complex thing to hold onto the weight of being Black in America. Across the community, people are waxing and waning on how incredulous these times actually are, rolling from feelings of heightened anger and resistance to an exasperation that there is really nothing new here. There is the belief that this administration presents a new threat — or at least a unique one — that the country hasn’t seen in some time. As the Trump presidency digs in its heels — a week ago signing executive orders that the White House blog labels “pro-law enforcement and anti-crime” — many are feeling that what organizers are doing today is just touching the surface of what is needed. The past has many clues from the civil rights work to the the Black Power ideology that needs to be studies and upgraded but not forgotten. Newsome climbed up a pole to remove a symbol of hate and oppression, many feel our resistance is sliding down a pole as the symbols and actions of white supremacy again rises back up.