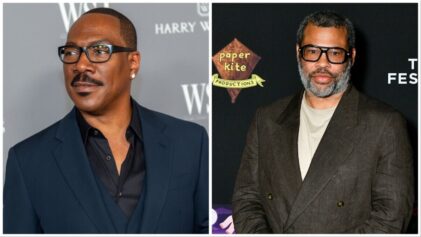

Samuel L. Jackson, Daniel Kaluuya, David Oyelowo

In a year with relatively few bright spots, one small but encouraging trend in 2017 is the rise of the Black auteur and the unambiguous success of films focused on the African-American experience. From “Hidden Figures” grossing over $200 million domestically to the shocking — and totally deserved — triumph of “Moonlight” over “La La Land” for Best Picture at the Academy Awards, the level of respect, attention and, quite frankly, love, that Hollywood has bestowed upon films portraying the African-American experience seems to be at an all-time high. Perhaps, the most shining example of the increased presence of African-Americans in front of and behind the camera is Jordan Peele’s critically acclaimed and commercially successful debut film, “Get Out.”

If you’ve been living under a rock and aren’t familiar with “Get Out,” you might want to run to the nearest AMC and get ready to wait in line because this movie is on fire. Since it premiered on February 24, “Get Out” has managed to sustain a near perfect 99 percent rating on Rotten Tomatoes and has grossed well over $100 million domestically. Those statistics are impressive on their own, but when you add that “Get Out” is a completely original, franchise-less, satirical horror flick from an untested Black director, Peele is quite literally making movie history.

“Get Out” follows Chris, an African-American photographer, as he travels upstate with his white girlfriend, Rose, to meet her family for the first time. What begins as a familiar “meet the parents”-type scenario takes a sinister turn as Chris and the audience learn that Rose and her lily-white family, while seemingly “woke”, are not to be trusted. In his directorial debut, Peele, who broke out as one half of the viral comedy duo Key and Peele, creates a popular horror film with insightful observations about race in American society to create a thoroughly terrifying yet eerily familiar story of what it means be an African-American man living in a society operated by and for white people. As a young, Black man named Chris (I know), I can personally attest that “Get Out” is sharp, scary, hilarious and painfully familiar.

However, a recent controversy has jumped to the forefront in the making of the movie. The star of “Get Out,” Daniel Kaluuya, is, in fact, not African-American at all. He’s British.

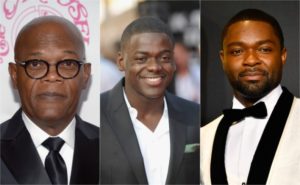

While this distinction might seem like splitting hairs, the decision to cast a Black British actor in a role written as African-American has resurrected a long-simmering debate about representation and opportunity in Hollywood. In an interview with Hot 97, African-American actor Samuel L. Jackson spoke about his disappointment with Kaluuya’s casting, saying “I tend to wonder, what would that movie have been when an American brother, who really feels that and understands that… cuz [sic],I mean, Daniel grew up in a country where, you know, they’ve been interracial dating for a hundred years … What would a brother from America have made of that role?”

It should come as no surprise that Jackson’s remarks were considered controversial in the entertainment industry, prompting some prominent Black British actors to weigh in. John Boyega, one of the stars of the most recent “Star Wars” reboot, quickly took to Twitter to publicly denounce Jackson for his comments, writing “‘Black Brits vs. African Americans’ a stupid ass conflict we don’t have time for.” Kaluuya himself eventually responded to Jackson’s comments, stating, “I resent that I have to prove I’m Black.” Amid the controversy, Jackson himself eventually rolled back his comments about Black British actors, telling the Associated Press, “It was not a slam against them, but it was just a comment about how Hollywood works in an interesting sort of way sometimes.”

However, Jackson isn’t necessarily wrong to question the “interesting sort of way” that Hollywood tends to prefer non-U.S.-born Black actors over their African-American peers. From Nigerian-born Lupita Nyong’o and Englishman Chiwetel Ejiofor’s performances as Patsy and Solomon Northrop in the Academy-Award winning “12 Years a Slave” to the British David Oyelowo and Carmen Ejogo’s respective turns as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and his wife, Coretta Scott King, in “Selma,” there is a distinct history in Hollywood of casting non-U.S.-born Black actors in African-American roles. These roles are typically the most high-profile and awards-bait opportunities for Black actors — serious, nuanced, complicated characters usually based on historical figures. Of the aforementioned actors, four out of four played a dramatic role based on a real person and three out of four received Academy Award nominations for their performances, with Nyong’o going on to win the Oscar for Best Supporting Actress.

Look back at the most recent batch of Oscar nominees and you’ll see a similar trend. Of the six Black acting nominees (the most in Academy history), two of them — Naomie Harris for “Moonlight” and Ruth Negga for “Loving” — were British and played African-American characters. The structural bias that seems to prefer non-U.S. actors of color to American actors is so pervasive that it has become a sort of in-joke within the small community of actors of color. After receiving the Best Supporting Actor Oscar for his turn as Juan in “Moonlight,” African-American actor, Mahershala Ali joked that he was “so fortunate that [British actor] Idris Elba and David Oyelowo left [him] a job.” African-American actor and comedian Larry Owens does a hilarious bit as a Black British actor by the name of “Chuwuwike Onyejiaka” winning an Oscar for playing the founder of Famous Amos cookies, Wally Amos. He keeps accidentally calling the cookies “biscuits.” It slays every time.

The question then becomes how would “Get Out” have turned out if it had starred an African-American actor? How would any of these movies have turned out if African-Americans had played the roles instead of their British peers? Would the movies and performances be better, more deeply felt, more riveting, more personal in some way? Does it even really matter? And furthermore, as an African-American actor myself, can I even objectively analyze the issue at hand?

To answer the last question first, yes I can, and here’s why: Beneath the superficial controversy Jackson reignited about the turf war between Black Brits and African-Americans in Hollywood lies a more profound and philosophical question about the fundamental relationship between authenticity and entertainment. Implied in Jackson’s disappointment about Kaluuya’s casting is the equal but opposite notion that Jackson is actively interested in seeing African-American characters played by actors who have authentically lived the African-American experience in their own personal lives. When we take into consideration an actor’s background in determining whether or not he or she should play a certain part, as Jackson did with Kaluuya, we are discussing the amount to which an actor’s own life outside of the film and the imaginary experiences of the character are supposed to intersect: How thoroughly does the actor’s “authentic self” — her place of origin, her ethnic background, her upbringing, her favorite foods, etc — overlap with what we know about the character she is playing?

The idea that an actor’s authentic self has to overlap with their character in an essential way is a relatively new development in the history of the entertainment industry. Until fairly recently, no one particularly cared about how an actor’s personal life intertwined or dovetailed with the role that they played. There was no public outrage when white actor Lawrence Olivier donned blackface to play “Othello” in the 1965 film, and no one batted an eye when Charlize Theron basically won an Oscar for not wearing makeup, gaining 80 pounds and pretending she was a serial killer instead of a literal supermodel. Other prominent examples of award-winning performances by actors whose “authentic selves” share absolutely nothing in common with the character they are playing are Jared Leto in “Dallas Buyer’s Club” (Leto isn’t a trans woman), Eddie Redmayne in “The Theory of Everything” (Redmayne doesn’t have ALS) and Ben Kingsley in “Ghandi” (Kingsley isn’t Indian), to name a few. The point is clear: For a very long time, people simply didn’t care if the personal life or history of an actor overlapped in any authentic or meaningful way with the character being played.

However, as society has progressed and pressed further into the digital age, questions about authenticity and “who has the right to play what part” have grown louder in the entertainment industry. For starters, previously popular forms of entertainment that fully exploited and made a mockery of the actor’s “authentic self” in relation to the character he was playing — like blackface, for example — are now rightfully deemed as offensive, racist and completely unacceptable. Likewise, with the advent of the Internet, we now have faster access to more information than ever before about the personal lives and stories of the actors and celebrities that grace our movie and television screens. Because of Facebook, Snapchat, Wikipedia, et al., we know too much to completely ignore glaring incongruity and discrepancy between an actor’s personal life and the character they are playing. It’s become more difficult to blur the lines between fact and fiction, real and fake, true and false. In 2017, we have the receipts and we check them, constantly.

And when we check the receipts for “Get Out,” Kaluuya’s casting doesn’t totally add up. If we are to truly believe that the African-American experience is singular and unique, how can someone who hasn’t lived that experience bring the same depth or gravitas to a role as someone who has? How can you ever truly understand what it is like to be a young Black man who grew up in the good ol’ US of A?

The meritocratic, hardworking, industrious part of me thinks, “Shouldn’t talent rule the day?” Jordan Peele cast Kaluuya because he thought he was best person for the role. If Peele chose Kaluuya to be the vessel to tell his story, who are we to judge whether or not Kaluuya’s personal life experiences make him eligible for the role? Anyone who saw Cynthia Erivo’s breathtaking, Tony Award-winning performance as Celie in “The Color Purple” last season on Broadway would be, quite frankly, absolutely insane to say she didn’t deserve the role or wasn’t able to connect and share Celie’s pain and the pain of African-American experience because she’s British. And, if I’m being perfectly honest, I had no idea until after I saw the movie that Kaluuya wasn’t African-American and his British heritage in no way distracted me while watching the movie. Looking at the critical acclaim and commercial success of the movie, I don’t think it’s going out on a limb to say that the vast majority of moviegoers agree with my sentiment.

But, while that’s all true, there is another, perhaps more emotional part of me that, as an African-American, is still tacitly annoyed with Kaluuya’s casting. It stings to see such an amazing opportunity taken away from an African-American actor. After years of bearing witness to minstrelsy, blackface, white-washing and cultural appropriation, I understand the desire to want our African-American characters to be played by authentically African-American people. After all we’ve been through, is that really so much to ask?

The beauty of film as a medium is that it allows us to quite literally see the world through someone else’s eyes. To walk in someone else’s shoes, whether they are 6-inch Louboutins or muddy combat boots. To view the world from behind their camera lens or their aviator shades or from their sunken place. Getting worked up about how an actor’s personal life overlaps with the character they portray, while undeniably fascinating, ultimately distracts us from the art itself and can potentially send us down a dangerous path. If every actor is only allowed to play characters that they have a specific shared history with, no one will ever be forced to grow or experience something new. It leaves actors and audiences alike with nothing new to explore; it stifles the imagination and creativity of everyone involved. And furthermore, just because an actor does overlap with the character they are playing in some essential or authentic way definitely does not mean that they are necessarily going to knock the role out of the park. It’s important to remember that every individual, whether they are African-American, British, Chinese, Latino, Norwegian, has a unique and singular set of experiences and, as such, so does every character. Excluding, say, a whole group of people from having an opportunity because of something as trivial as where they are born doesn’t seem like a great solution to any problem, now does it? Looking at you, Mr. President!!!

Of course, the problem isn’t with Kaluuya or Jackson but with the industry itself. Even with the recent boom in minority-centered films, there are still very few opportunities for marginalized actors in Hollywood. The simple answer is that if there were more quality opportunities for marginalized communities in Hollywood, this would most likely be a moot point; there would be enough roles to go around. But, at the present moment, there are still not enough seats at the table and, as such, it’s forcing minority actors of all races and backgrounds to fight over the scraps. Unfortunately, we still live in a world where Emma Stone can play an Asian-American woman in a major motion picture. Where the cast of “Exodus: Gods and Kings,” a movie set in ancient Egypt, is a veritable who’s who of white movie stars. Where multiple important people in the entertainment industry actively said, “Yeah, that sounds like a great idea!” when someone suggested that Joseph Fiennes should play Michael Jackson on TV.

So, at the end of the day, I stand by Daniel Kaluuya’s casting and his performance in “Get Out.” He did a bloody good job and deserves all the Pimm’s cups and biscuits he will receive as a result of the film’s very deserved success! While I get where Jackson is coming from, I don’t believe that an actor’s authentic self needs to match up 100 percent or 50 percent or even 1 percent with the character he/she is playing. Rather than focus on who’s British or who’s American, what we need to do is give people from marginalized communities the opportunity to tell their own stories. If 2017 is any indication of what happens when we finally start giving a voice to minorities, then truly everyone wins.

—————————————————————————————————

Chris Murphy is an actor, writer, and tutor currently living in New York City. He recently graduated from Princeton University with a degree in English Literature. For more pop culture analysis, you can follow him on Twitter @christress