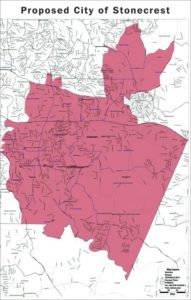

When Jason Lary presented a plan four years ago to create a new city out of unincorporated south DeKalb County — an area that’s 95 percent black — folks had questions.

After all, the story of new cities around Atlanta has been one of white exiles from Atlanta leaving for unincorporated county land, building rich communities with that financial capital, then raising a wall between themselves and Black county political majorities. Why would a bunch of Black people think that’s a good idea?

Property values in the area Lary wanted for a new city had cratered. Homes in south DeKalb were regularly selling for under $30,000 after the housing bust. Stonecrest Mall lay at the center of it, a snakebit commercial complex that never quite got off the ground after the dot-com bubble burst, suffering a second wave of anchor-store departures during the recession.

How do you build a tax base out of this? How could Lary convince people that the creation of a city with city services paid for by additional city taxes on these properties made the most sense for a community of Black people barely hanging on by their fingernails?

Lary, a music promoter and business development executive for Kaiser Permanente, told people then that he personally had lost two-thirds of his own property value, so far. If Stonecrest Mall failed, he said he expected to cut his home value in half again.

His own financial survival depended on policy decisions on crime and zoning and development he had no control over. He had no faith in the state or county’s elected leaders to help solve a problem that was fundamentally local.

“You cannot conquer a people,” he said of convincing voters. “They have to want it.”

Well, they wanted it.

About 60 percent of voters approved the incorporation of Stonecrest in November. The vote shocked almost everyone except the people who actually live there.

“The other cities had stirred the soil for it,” said Jimmy Clanton Jr., a web developer and local activist who is now a candidate for a City Council seat. “Having your boots on the ground and knowing what the people are thinking, I’d heard the rumblings. I think people were disappointed with the government of DeKalb County. And then there’s the hope that things will become better with change.”

Republican leaders bristle at the suggestion that race underpins the incorporation movement in metro Atlanta, but the political effect has been fairly plain — new cities mean white leadership in Black counties.

Sandy Springs voters complained of Fulton County using its affluent exurb as a piggy bank while shortchanging them on services. The Georgia Legislature loosened the rules for creating new cities in 2005 in one of its first acts as a Republican majority. That allowed for the creation of a city of Sandy Springs in Fulton County. The county, home to the city of Atlanta, has a black plurality and is politically dominated by Democrats.

To some degree, the commercial center of Atlanta moved north to places like Sandy Springs and Alpharetta after Black political leaders took power and white voters moved away in post-segregation white flight.

One by one, affluent communities in metro Atlanta’s orbit — Brookhaven, Chattahoochee Hills, Dunwoody, Johns Creek, Milton, Peachtree Corners — began creating cities to handle their own zoning decisions, policing and public services. Of the more than 60 municipal elections in these new cities since then, exactly one Black person has won elected office. One.

If a city can provide a service — say, policing or road maintenance — it can charge a tax in place of the county for the work. With more tax revenue per property, these affluent new cities can often offer the same services at a lower tax rate.

That forces the county to raise taxes or reduce services to make up the difference. It’s a vicious circle for people left in unincorporated county areas. Each new city makes life more expensive for the people left behind, encouraging areas that could be financially self-sustaining to incorporate.

Stonecrest, however, has no interest in being left behind.

To some degree, Stonecrest has been passed over by the most affluent of the recent south-moving Black households, which have favored the employment options of Cobb County or the excellent schools of Gwinnett County. But, the place remains fundamentally middle class. Every census tract there has an average annual household income in the middle 20 percent, between $42,000 and $68,000 a year.

It is not poor. The income is there. The value just doesn’t reflect it.

The foreclosure crisis never really left this community. Today, post-recession, single-family houses still sell in a market conquered by foreclosures that keeps average home values at about $109,000, about 60 percent of the metro average. Prices remain 25 percent below the pre-recession peak, even as home values have completely recovered in most of DeKalb County.

The loss has been a blow to people who view themselves as America’s aspirational Black middle class. Instead of home renovations and business ventures funded from real estate appreciation, they find themselves surrounded by dollar stores and cheap restaurants, even though they have the income to support a better lifestyle. The negative home equity leaves them trapped in place.

Beyond creating a foreclosure registry and some new codes relating to the maintenance of foreclosed property, DeKalb’s county government has done little to address the loss of economic value here, even as the more-affluent communities north of Stonecrest blossom.

“Voters wanted to see the southside be just as important as the north side of the county,” said Mary-Pat Hector, a young political activist with the National Action Network now seeking a City Council seat. “They voted on it to see job growth and economic empowerment, and they wanted to see leadership with a high moral compass.”

The political turmoil in DeKalb’s county government added a sense that the corruption problems made governance difficult. The county’s chief executive officer was appealing a criminal conviction and had been removed from office at the time of the vote in November. For nearly two years, the county commissioner covering the Stonecrest area had been filling in as chief executive, leaving the community with less representation.

“We had a void for so long,” said Eric Hubbard, an activist who was pressing for Stonecrest, and is now a City Council candidate. “They want people who are going to do their job. We can have a strong government or a weak government.”