“When it comes to the earnings gap between black and white men, we’ve gone all the way back to 1950.”

These are the words of Patrick Bayer, an economist at Duke University who helped co-author new research examining the wage gap between working-class men over the past 75 years. The paper, published in the National Bureau of Economic Research this week, found that the Black-white earnings gap narrowed during the civil rights era but began widening again in the 1970s.

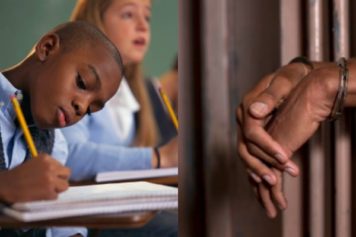

The prospect for economic growth turned much bleaker when researchers examined Black men specifically along educational lines; wage disparities between college-educated Black men and those who are less educated hit an all-time high.

Increased access to higher education and high-skilled professions has fueled growing salaries for Blacks at the top, but authors of the study noted that Black men at the bottom haven’t fared very well, as high incarceration rates and the decline of working-class jobs have ultimately ruined job prospects for those with a high school education or less.

“The broad economic changes we’ve seen since the 1970s have clearly helped people at the top of the ladder,” Bayer said. “But the labor market for low-skilled workers has basically collapsed.”

“Back in 1940, there were plenty of jobs for men with less than a high school degree,” he added. “Now, education is more and more a determinant of who’s working and who’s not.”

The paper, co-authored by economist Kerwin Kofi Charles of the University of Chicago, also revealed that the number of nonworking men overall has grown substantially over the past few decades. The number of white men not working jumped from 8 percent in 1960 to 17 percent in 2014. The numbers were much worse for African-Americans, as 19 percent of Black men were reported as not working in 1960 compared to 35 percent in 2014. These numbers included men who were incarcerated or just couldn’t find work.

Bayer said the stark disparities could have been much worse if Black men, or Black people in general, hadn’t made educational gains over the span of 75 years.

“Strong racial convergence in educational attainment has been counteracted by the rising returns to education in the labor market, which have disproportionately disadvantaged the shrinking but still substantial share of blacks with lower education,” the study reads.

Bayer and Charles’ findings showed that while educational achievement has opened up new doors of opportunity for wealthy, educated Blacks, there needs to be a renewed focus in closing the racial achievement gap and offering new job prospects to lower-skilled and less-educated workers.

“We clearly need to create better job opportunities for everyone in the lower rungs of the economic ladder, where work has become increasingly hard to come by,” Bayer said.