Calhoun College, Yale University

The colleges and universities of America are emerging as a battleground in the fight for racial justice, and the struggle to reclaim history and come to terms with a legacy of oppression. All of America’s institutions were complicit in the enslavement of Africans, and certainly higher education was no exception. Within these halls of learning, leaders were cultivated, society was conditioned and indoctrinated with certain values, and slavery was upheld. Universities exploited Black people and profited from their bondage. And now, at a time when Black Lives Matter, a reckoning with the past is unfolding.

Meanwhile, as these colleges commemorate the Black bodies they once chained up — some even offering apologies — the question that arises is whether additional debts have yet to be paid, and if so, to whom.

Recently, Harvard University unveiled a plaque to commemorate four enslaved Black people who labored in the president’s residence in the 1700s. And at Harvard Law School, student protests led to the removal of the school seal, which was the family seal of slave owner Isaac Royall, who donated his estate to the first law professorship at Harvard. Now, Reclaim HLS — the student group involved in racial justice activism around the Royall seal and the defacing of portraits of Black professors — is demanding an end to tuition:

The effects of HLS’ astronomical tuition fees are racially biased. Due to the legacy of centuries of white supremacy and plunder, people of color are less likely to have amassed wealth in the United States. Therefore, these fees disproportionately burden students of color, not only by creating a barrier to attending HLS, but also by constraining the career choices of those who do attend by saddling them with hundreds of thousands of dollars in debt. How can Harvard Law graduates be expected to advance justice or the well-being of society when they are forced to make career decisions based on paying off this burdensome debt?

For Rena Karefa-Johnson — a third-year student at Harvard Law School — there is a direct link between slavery and the issue of tuition.

“The legacy of slavery ties in with the seal very explicitly. More broadly, the seal was first chosen solely on the grounds that its original owner was the first benefactor of the law school and the wealth he derived from it came from the labor of enslaved Africans,” she told Atlanta Black Star. “Our financial justice campaign is, in part, about returning the benefits of that labor to the descendants of those who actually earned it.”

Reclaim Harvard Law/Facebook

Karefa-Johnson believes that universities such as Harvard owe a great deal to Black people.

“The fact that institutions like Harvard are beginning to recognize their ties and debts to enslaved Africans is an important first step. But recognizing this truth is different from reckoning with it. Reckoning is what these institutions owe Black Americans,” she added.

“This is what Reclaim HLS’s demands are about: reckoning not only with the existence of slavery, but with its legacy. Apologizing for slavery is nice. But what’s crucial is using the lessons of the past to change your way of thinking about the present and the future,” the student-activist noted. “Had the Harvard of yesterday done what we are now asking it to do — listened to the most marginalized students and workers in the Harvard community when they explain how the institution entrenches race, class and gender oppression both within the school and in society — then perhaps that Harvard would have been closer aligned with the abolitionists rather than the slaveholders.”

Craig Steven Wilder, professor of history at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, elaborated on the notion of universities being held accountable to their stakeholders and the Black community for their role in slavery.

“My sense is that these universities first owe themselves, their students and alumni, and their other constituencies the truth about their historical ties to slavery and the slave trade. This means taking institutional responsibility for the work of researching and making public the ways in which they both benefited from and participated in the slave economies,” said Wilder, who is author of “Ebony and Ivy: Race, Slavery, and the Troubled History of America’s Universities.”

At Clemson University, a groundbreaking ceremony to honor its enslaved workers came days after a Black history banner on campus was adorned with bananas. The desecration led to sit-ins, and five students were arrested, as Atlanta Black Star reported. Concerned Clemson students made a list of demands to the school administration, including hiring more faculty and administrators of color, resources for underrepresented students, a multicultural center, and changing the names of offensive buildings such as Tillman Hall — which is named after a white supremacist governor of South Carolina. The students also called for the university to denounce the “Crip’mas Party,” in which white members of the Sigma Alpha Epsilon fraternity members held a gang-themed event in 2014.

#BeingBlackAtClemson means waking up to bananas hanging from a sign in front of the university’s plantation house. pic.twitter.com/zjxQiyTioi

— See The Stripes [CU] (@TigerStripesCU) April 11, 2016

At Yale University, students of color presented the school administration with a list of demands, urging the school to “implement immediate and lasting policies that will reduce the intolerable racism that students of color experience on campus every day.” This included the removal of the title of “master” used for the faculty members who head the residential colleges, according to The Washington Post. Moreover, the students called for the renaming of Calhoun College, a residential community named for John C. Calhoun, a Yale alumnus from South Carolina and a leading supporter of slavery. The students demanded the house to be renamed after a person of color.

In 1838, Georgetown University in Washington, D.C., sold 272 of its slaves to keep the Jesuit institution afloat. As The New York Times reported, the college relied on Jesuit slave plantations in Maryland for revenue to maintain its operations. The sale of African children, women and men — amounting to $3.3 million in today’s dollars — was used to pay off Georgetown’s debts. Student protests led to the removal of the names of the college presidents involved in the sale from campus buildings, and a university working group is charged with finding ways for the institution to acknowledge and repair the damage for its role in slavery.

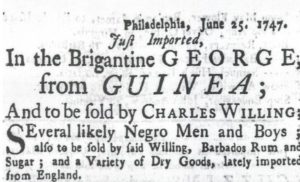

“Ebony and Ivy,” by Mr. Wilder, cites this ad for the sale of slaves by a trustee of the University of Pennsylvania. Credit Pennsylvania Gazette

Wilder believes that such efforts on the part of universities require input from Black people.

“This is also part of the process of addressing these injustices by respecting and acknowledging the humanity of enslaved people. Several universities have debated and implemented steps toward restorative justice, including scholarships, academic programs, faculty hiring, etc.,” Wilder said. “These are reasonable first actions, but I would also urge university administrators to invite Black communities into the discussions of how to respond to this past. We can use this moment to transform ideas about belonging and the structures of decision making on our campuses.”

In 2006, Brown University disclosed its extensive ties to slavery and its involvement in the transatlantic slave trade. Brown formed a Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice, and has pledged $100 million over the next decade to address campus racism and provide a more inclusive environment, according to a report from the president of the institution in February 2016. In addition, the university announced plans to circulate its report publicly, and “sponsor public forums, on campus and off, to allow anyone with an interest in the steering committee’s work to respond to, reflect upon, and criticize the report.”

Jumoke Ifetayo, the National Male Co-Chair of the National Coalition of Blacks for Reparations in America (N’COBRA) told Atlanta Black Star that universities should hold a major conference each year dealing with the issue of reparations, “because that gives academic credibility and almost institutionalizes the conversation.”

Ifetayo said these forums would lead to books, films and journals to educate the public and raise awareness. More education is needed, he believes, as many people, particularly whites, are not taught about Black contributions to history in school.

“All of the students need to learn African history and the role we played in the Revolutionary War and the Civil War, and science and invention,” Ifetayo said. “There is a whole lot of contribution, and people need to have that knowledge base of our contribution. People know about Thomas Edison, but they don’t know about Lewis Latimer,” he added.

Ifetayo supports efforts such as more scholarships for Black students, more African-American professors, speakers on Black issues and initiatives such as those undertaken by Brown University. He noted that while most African-Americans support reparations, there are many misconceptions about reparations.

“People won’t support a check, but they support free education, and learning more about their history,” he said.

However, he rejects any effort to calculate what is owed to Black people solely in terms of free labor.

“Reparations is about repair. If someone steals your car, you say you only want the money for the gas they burned? We don’t want compensation for picking cotton. Our language and culture were stripped from us. Our behaviors today come from seeing our grandfather lynched,” Ifetayo said. “So what is the cost to repair us for what was done?”