But with racial tensions simmering over police abuses of African-Americans, the on-court hurdles faced by Cleveland, the team, pale compared to the challenges confronting Cleveland, the city.

James hinted as much recently, when asked about the acquittal of a white police officer who killed two unarmed Black people. And then he said something that, though barely noticed, came off as a rather strange idea.

In a plea for peace, James offered sports – sports! — as a means of helping heal America’s racial problems.

“Sports in general, no matter what city it is, something that’s going through a city that’s very dramatic, traumatizing or anything of that case, I think sports is one of the biggest healers in helping a city out,” James told The New York Times.

Much to his credit, James has proven to be socially conscious. For sure, he’s a refreshing change from the image of the apathetic spoiled superstar (think Kobe Bryant).

But even “King James” is subject to occasional lapses. His heart may be in the right place, but his assumptions about sports and healing seem, well, a bit puzzling.

There’s no evidence to show that, in these days, with rogue police using Blacks as target practice, sports can serve as a racial balm.

So what could lead James to even think such a thing?

Here’s a theory: James spends much of his time inside basketball arenas. At first blush, the racial view from there can be deceptively rosy. In those places, sports does seem, on the surface at least, to generate a spirit of cross-cultural harmony.

You see it, implicitly sometimes, through broadcasts on the TV screen: You see fervent fans wearing the same team colors. They appear as a virtual unified rainbow nation. Clamoring, side by side, in the stands together, they seem so thoroughly integrated that it’s easy to forget that race in America is even an issue.

But when you examine the overall racial climate in this country, game or no game, another, more sobering picture crystalizes. Reflection on the cold, hard facts might reveal that James, bless his heart, may be engaging in wishful thinking.

The truth is, among the most zealous fans, sports may present isolated moments for individuals to connect across racial lines. But on a broad scale, rooting for the same team cannot be confused with racial bonding.

Anybody who sips that flavor of Kool-Aid has probably failed to grasp an aspect of our collective psyche that is as American as the Fourth of July. For centuries, white Americans have learned to compartmentalize adoration and contempt for Blacks. In this country we are very experienced at this — we nimbly juggle racial contradictions, especially with regard to Black athletes and sports.

Remember former L.A. Clippers owner Donald Sterling? Dude owned an overwhelmingly Black hoops team and, at the same time, begged his young boo to stop mixing publicly with African-Americans.

No racial healing going on there, for sure.

Remember Bruce Levenson, formerly of the Atlanta Hawks? He was part-owner of a team in a very Black city, with a strong civil rights identity. Yet he complained that — get this — too many Black folks were attending games.

Consider this one: A federal report last year found that Cleveland officers engaged in a pattern of “unreasonable and unnecessary use of force,” especially with regard to African-Americans. It’s no stretch to assume that many of the officers cited for abusing Blacks are huge fans of LeBron James.

To understand such glaring paradoxes is to know that, on any given day in sports venues across the country, it is entirely usual for many whites to cheer their favorite Black athletes and simultaneously loathe African-Americans in general.

Even prominent African-American ballers are sometime served a bitter dose of that reality, which we Black commoners deal with every day. Black jocks are sometimes put on notice that the line between adulation and hatred is extremely thin.

Ask Seattle Seahawks defensive back Richard Sherman. He was widely labeled a “thug” for simply speaking with what some whites considered too much postgame passion.

Ask LeBron James, for that matter. Four years ago, he chose to leave the Cavaliers for the Miami Heat. From the day of the announcement, he saw his jerseys – and his likeness – burned in effigy, all over Cleveland.

Given the protracted venom spewed at James, even by the Cavaliers’ owner, it makes you wonder, how could James, of all people, believe sports helps heal racial tensions?

Who knows? Maybe the endless praise lavished on him by adoring fans of every ethnic persuasion inspires selective amnesia. Or maybe that over-the-top Nike TV commercial had the effect of blurring his vision. https://youtu.be/n6S1JoCSVNU.

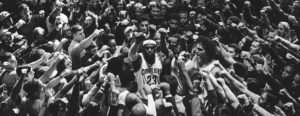

Titled “Together,” the Nike ad aired during James’ initial return to Cleveland. It featured a series of dramatic shots of James, flanked by multi-ethnic throngs of people, fists clenched, and united in purpose.

The implicit message was that with his return, all was forgiven; James would help Cleveland heal its economic woes, and maybe engender racial accord.

But that was then.

Since then, 12-year-old Tamir Rice was gunned down by police while playing at a park. And now, a Cleveland judge has ruled that Officer Michael Brelo acted within his rights when he and other police officers fired a barrage of 137 bullets into a car, killing Timothy Russell and Malissa Williams, who were unarmed.

If James knows nothing else, he should understand this: No amount of sports or slick Nike ads will bring back those lives, which were senselessly snuffed by authorities who were sworn to protect human life.

And, as protesters in Cleveland are now making clear, not even an NBA championship can heal those wounds.