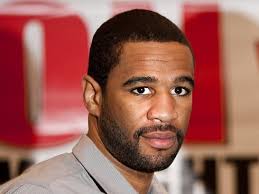

Victory for Lamont Peterson is measured differently from the rest of us. That’s how it is when you spend ages 8 to 10 with your younger brother homeless, living in abandoned cars and buildings in Washington, D.C., surviving on guile a kid that young should not have to tap into and a will many people much older do not possess.

That’s the early story of the IBF light welterweight champion, who takes on heralded Danny Garcia on April 11 at the Barclay Center in a non-title fight. When he engages in this bout that will be broadcast live on ABC, the 36th of his two-loss career, he won’t be thinking about his challenging past: Homeless. Foster homes. The streets.

But he will carry with him into the ring that experience, that pain, that fear, that strength, that anger, that will, that loneliness, that something all men cannot claim. It’s like Garcia will be competing against more than Peterson. Garcia will be fighting against Peterson’s life.

“Life is hard,” Peterson said during an interview with Atlanta Blackstar. He is soft-spoken and humble, the antithesis of what champions in this sport almost always are. In everyday life, he prefers quiet time out of the spotlight. He trains harder than most and has a small circle of family and friends he’s known much of his life.

“I don’t trust a lot of people,” he said.

And for good reason. As a child, his father was in prison and his mother, overwhelmed by trying to raise 12 children by herself, turned to alcohol. The family imploded, with some of his siblings, the older ones, staying with a grandparent. Others scattered. Lamont and his younger brother Anthony fended for themselves on the streets.

For two years they lived on the go. Lamont and Anthony found empty buildings or abandoned cars and made them temporary shelter. They would wipe windows of cars at stoplights in the hopes of receiving small change to get food. The boys eventually bounced around various foster homes, even leaving one they did not like and returning to the streets. Peterson said he enrolled in Cardozo High School, but did not finish.

Lamont knows his story is almost unimaginable. But his plight has been well-documented in D.C., where fans laud Peterson for his achievement and as someone who has resurrected boxing in a city that loves the fight game.

“That (upbringing) made me more responsible,” Peterson told ABS. “I didn’t trust people. I learned not to depend on anyone. It made me more driven as a person and a fighter.”

The only constants in his life were his brother and boxing gyms. They would end up there almost daily, which is where Barry Hunter first encountered Peterson.

A renown trainer in D.C., Hunter said he saw something in the kid beyond obvious boxing skills. But Peterson was extremely guarded.

“I didn’t like grown-ups at all,” Peterson explained. “At all. Didn’t get along with them…I was a man. Took care of myself. No one ever told me to go clean your room — or go clean yourself. Homework? Go to school? Nobody told me anything. I did what I wanted to do.”

Yet Hunter struck a chord with the child and ultimately became his trainer and surrogate father.

And he remains Peterson’s trainer as he embarks on a quest to more boxing prominence.

“Boxing is perfect for me because it’s an individual sport; you don’t need anybody,” Peterson said. “It’s just you against the other guy. In the ring, you only rely on yourself. That’s been me all my life.”

He said he will defeat the undefeated Garcia on April 11 not only because of physical styles, but because “I can think under pressure,” he said. “Fighting is not just about brute force. A lot goes on and you have to handle it mentally. You have to think, make a way. This is where my upbringing helps.”

The same can be said for his brother, Anthony, who is 34-1 and will fight on the undercard that night. The brothers who endured so much both became amateur boxing stars and remain Super Glue-tight, living together in D.C.

At 31, Peterson said he hopes to compete until he is 35. He’s raising his six-year-old daughter, Sommer, as a single father with full custody. “I want to retire with enough money to enjoy life for all the work I put into this,” he said.

At that point, he will slip into the anonymity he prefers. But he will go having accomplished so much in the ring, but much more outside of it.