Instead of quickly jumping to offense, a more edifying response would be to embrace the fact that these dishes are a part of the community’s cultural heritage and encourage institutions to look beyond the legacy of slavery to educate the public about how so much of modern African-American cuisine was actually derived from African dishes.

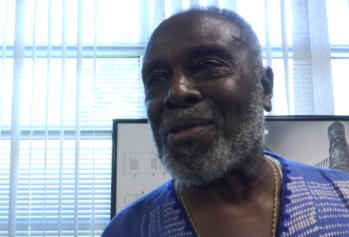

“When we look at the Black world, so much of it is traceable back to Africa—African-American cuisine in America and even cuisine in the Caribbean,” Mausiki Scales, professor of African-American studies at Georgia State University, told Atlanta Blackstar. “There’s a rich tradition that informs how we look at food. We don’t need to always react when someone throws some of that in our face. Even watermelon is traceable to some part of Africa.”

Rather than embarrassment, Black people might feel pride that they come from a people creative enough to take the foods and herbs available to them in America and form dishes closely linked to the foods they were forced to leave behind in West Africa.

This latest controversy bubbled up on the campus of Wright State University, just outside Dayton, where the school’s food vendor decided to design a Black History Month menu that included chicken, mashed potatoes, collard greens and cornbread under pictures on the digitized menu board of Martin Luther King Jr., Jesse Owens and other famous Black figures.

The menu coincided with “Daughters Rising from the Dust: Children of ‘The Movement,’ Speak Out!” a panel discussion at the school that included Ilyassah Al-Shabazz, daughter of Malcolm X and Betty Shabazz; Reena Evers, daughter of Medgar Evers; and Mary Liuzzo Lillieboe, daughter of Viola Liuzzo.

When an alumnus took a picture of the menu and posted it on social media, a controversy was born. In response, Chartwells Higher Education Dining Services, the vendor in charge of the menu, released a statement that read in part: “Chartwells celebrates many national events on campus and tries to provide authentic and traditional cuisine to reflect each theme. In no way was the promotion associated with Black History Month meant to be insensitive. We could have done a better job putting this in context of a cultural dining experience. We sincerely apologize.”

Billy Barabino, a senior organizational leadership major from New Jersey and president of the Black Student Union, told the Dayton Daily News, “I was really hurt (by the menu). Extremely hurt. For me, it was a knock in the face for African (and) African- American individuals who have fought for us to be progressive. I was extremely offended by it because it minimizes who we are as people.”

It is understandable that in a nation where so much history is filled with attempts to demean and abuse Black people, the Black community would be sensitive to anything that appears to link to that ugly past, even if there was no intention to offend. Georgia State’s Scales said the offensive caricatures emerged primarily after Reconstruction as a reaction to the Black community’s newfound power. In an attempt to imply that Black people were descended from savages, many caricatures were born that featured Black people as “pickaninnies” eating foods with their hands, such as fried chicken and watermelon.

Scales said the Black community should be aware of not getting “distracted” by overreacting to issues like fried chicken on a menu, which serve to take the community’s focus away from fighting bigger and more important enemies like white supremacy and the institutional racism still present in so many sectors of American society.

Scales pointed to 1830 as an important year in the history of African-American cuisine because that year was the first time that Black people born in America outnumbered Black people born in Africa, who stopped being shipped over after the trans-Atlantic slave trade ended in 1807.

“When you’re looking at a diet informed by African heritage, even those born in America still had heavy reliance on Africans and on plants and herbs they used in Africa,” he said.

Wright State’s president, David Hopkins, tried to quickly rehabilitate his school’s image by pointing out the university’s commitment to diversity, singling out the forum featuring daughters of several civil rights leaders.

“I apologize to anyone hurt by the display,” Hopkins wrote. “To our credit, the menu was quickly removed. But the larger question remains: Why was it done? I will find out. We will take steps to prevent this kind of behavior occurring in the future.”

The blowup at Wright State is reminiscent of other controversial menus, such as the outrage last month when The Borgata casino in Atlantic City got in trouble because its restaurant decided to honor Martin Luther King Day with a menu special of fried chicken, collard greens and macaroni and cheese.