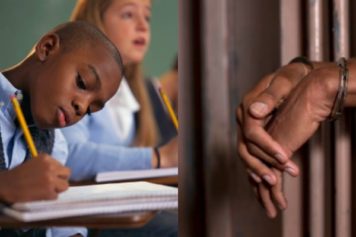

The graduation rates for Black college students have seen a slight increase in recent years, but many people agree that it’s not enough to argue that educational equality has been reached.

As universities across the country try to find ways to boost the graduation rates and grade point averages (GPAs) for their Black students, mentoring and improving the social climate have emerged as two of the most popular and, perhaps, the most effective solutions.

From discrimination in the classroom by professors to feeling excluded on campus, education experts argue that Black students are still facing great obstacles that their white counterparts don’t.

Many studies suggest that the key to preparing Black students for college is to actually prepare them for prejudice.

“Many African American students are unprepared for and unable to cope with the prejudice they encounter upon entering college,” Indiana University-Bloomington’s Marybeth Gasman wrote in a report titled “Mentoring Programs for African American Students in Predominantly White Institutions: Relationships to Academic Success.”

A study of 384 African American students in predominantly White colleges by Willie and McCord found that many students expect less prejudice and more social integration than they experience in the college environment. Researcher Claude Steele suggested that “Black students know that the stereotypes about them raise questions about their intellectual ability… they can feel that their intelligence is constantly and everywhere on trial.”

This has a major impact on their academic performance.

According to the US Department of Education, Black college students, when compared with other racial groups, have the highest dropout rate for both two-year and four-year colleges. For Black students at PWIs (predominantly white institutions) and HBCUs alike, completion of college is both directly and indirectly related to a blend of individual, environmental and racial experiences, which may be affected by interventions designed to reduce Black student dropout rates.

Those rare but effective interventions have been proven to be effective time and time again and helped lead one Georgia State student to academic success.

An African-American pre-med student, who opted to remain anonymous, said her entire outlook on education changed when the university placed her on academic probation but didn’t just leave her “out to dry.”

“A lot of schools will put you on academic probation and leave you out to dry,” she said. “They didn’t do that to me. Before they even talked about the problems with my grades they kind of asked me like, ‘What’s going on girl? Are you OK? How can we help because we see this a lot?’”

The 22-year-old student was struggling academically and even lost the state-sponsored HOPE scholarship during her second year.

“It was just hard for me to focus and I didn’t have anyone to talk to about it,” she said before explaining she was the first of her family to go to college.

That’s why many believe mentoring is so key.

A report, co-authored by the Dean of African American Affairs at the University of Virginia, Dr. Maurice Apprey, explained that the university focuses on “student peer-advising, faculty-student academic mentoring and advising, culturally sensitive initiatives and organized parental support.”

By focusing initiatives on boosting parental support and involvement with mentors on campus, the university has become a breeding ground for successful Black graduates.

Many prominent figures in education, including the CEO of the Thurgood Marshall College Fund, Johnny Taylor, have frequently pointed to the lack of parental support and guidance for Black students in college as a major factor contributing to low graduation rates and low GPAs.

Without that guidance, students can become discouraged and cheat themselves out of academic success.

Christopher Daughtry, a student at South Carolina’s Benedict College who was recently crowned Mr. Benedict and now serves as a mentor to many other students on campus, says it’s something he has witnessed himself.

“Sometimes I think it’s just being lazy,” Daughtry said. “Some of these guys just aren’t trying, but you see them partying all the time.”

By all means, Daughtry wasn’t “supposed” to be the academic success story he is today.

Growing up in a household with five other siblings, Daughtry is no stranger to financial struggles and the other adversities that many Black students face when pursuing an education.

The key, however, is having guidance and a mentor to help fight off the negative narratives that often leave Black students feeling defeated before their academic journey even begins.

Daughtry explained that as a mentor, he has to convince young Black students to stop thinking that academic success is impossible.

“I just think this narrative is problematic,” the New York native said. “Yes, we have to educate our young Black students on discrimination, but we also can’t create the message that it’s impossible to be successful unless someone else does something for you or that it’s OK to fail because the system was set up that way. No. It’s not OK to fail. No matter what challenges these people may have caused for you they didn’t take that book out your hands and they didn’t snatch you out the classroom, so as long as you’re there, in school, you have the ability to succeed.”

That ability to succeed is enhanced with the presence of mentors who can relate to Black students and an environment where these students feel comfortable and encouraged to thrive.

“Schools play a major role in providing educational information, helping students take advantage of educational opportunities, and preparing students for success in postsecondary education and the workplace,” an ACT Policy Report explained. “Strong school relationships can increase students’ educational expectations and postsecondary participation.”

This is a part of what makes an inclusive environment so key.

Many studies discuss the importance of feeling a connection to an educational institution and the ability to see professors as mentors.

Unfortunately, many Black students don’t feel that way in the classroom and are left feeling as if they don’t have mentors to turn to on campus.

“You feel really alone and you feel like there is nothing you can do about it,” the Georgia State pre-med student added. “There are times you literally feel your professor’s energy when they are speaking to you. It’s this weird sense of, ‘OK I’m dealing with the Black kid and I feel a little uncomfortable but I’m just going to smile and nod.’ It wasn’t always like that, but it only takes one or two times before you’re just like, ‘F**k it. I’m not talking to these people anymore. I’ll figure it out myself.’ ”

When it comes down to it, mentoring has the ability to not only keep Black students focused and positive but it also can create a connection between the students and the university.

This ultimately improves academic relationships and can make students of color feel more included and welcome on campus.

So while it is clear to see that academic success is possible for any student of any color, the additional obstacles that Black students are faced with have certainly caused a disparity in the quality of education these students receive.

When it comes to why Black students aren’t having the same academic success as their white counterparts, the majority of students interviewed by Atlanta Blackstar agreed that the answer “will never be clear cut,” but with so many key factors already being identified, one can only hope that more institutions will start implementing programs that tackle the lack of inclusivity on campus and the access Black students have to academic mentors.