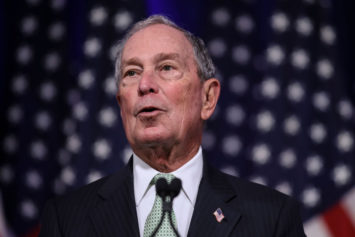

Mayor Michael Bloomberg got a swift kick from the New York City Council yesterday as it voted to override his veto and install an inspector general to review police practices, and to allow lawsuits against officers who use racial profiling as a reason for questioning someone.

The 51-member council needed 34 votes to override Bloomberg’s veto. The inspector general measure passed by a vote of 39-10, while the bill to allow lawsuits passed 34-15.

“It is a smart policing idea that will keep us the safest big city in America but do it in a way that reunites police and community, and do it in a way so that people who have a concern about policies and practices will have a place to go to have their voices heard,” said council Speaker Christine Quinn, a mayoral candidate, said before the vote.

The bills came after U.S. District Judge Shira Sheindlin ruled earlier this month that the NYC police department’s stop-and-frisk policy violated the constitutional rights black and Hispanic young men by stopping them without probable cause. To control the department, Sheindlin appointed a monitor she said would ensure that police act lawfully. The city is appealing the ruling.

“It’s a historic day,” said council member Jumaane Williams, the lead sponsor of the bill. “We have a lot more work left to do. But I’m very happy that the council did its job, moving in the right direction when others wouldn’t.”

The mayor, who has vociferously defended the controversial policy, blasted the council’s action.

“Today’s vote is an example of election-year politics at its very worst and political pandering at its most deadly,” the mayor said. “We will ask the courts to step in before innocent people are harmed.”

In a statement following the votes, the mayor said, “The communities that will feel the most negative impacts of these bills will be minority communities,” which have benefited most from reduced crime.

According to the New York-based Center for Constitutional Rights, the plaintiff in the federal suit, of the 4.3 million stop-and-frisk searches in the past nine years, more than 80 percent were of blacks and Latinos, and fewer than 1 percent of the stops led to recovery of a gun.

Bloomberg has pointed to the reduction in crime as the justification for the policy, saying stop-and-frisk helped reduce crime 34 percent since he became mayor in 2002.

Bloomberg, saying New York is the nation’s safest big city, accused the council of trying to win votes, not end racial profiling—which was outlawed in the city in 2004.

A New York Times poll revealed that New Yorkers are deeply conflicted about Bloomberg’s three terms in office, overwhelmingly embracing some of his most unusual and controversial behavior-modification policies, such as restricting smoking, encouraging biking and exposing calorie counts in restaurants.

But they also think he paid more attention to the concerns of the wealthy, he was disproportionately interested in Manhattan and he didn’t do enough to improve the public schools.

Asked to rate Bloomberg’s 12 years as mayor, 52 percent describe them as fair or poor, compared with 46 percent who label them as excellent or good. Compared with past mayors, 38 percent ranked Bloomberg as average, which could not be welcome news to a man who thinks very highly of himself. Twenty-one percent say he is above average and 15 percent say he is one of the best.

As for quality of life in New York, 40 percent say it has stayed the same, 35 percent think it has become better, and 23 percent say it has gotten worse.