The city of New York has made a major concession in its battle to keep its controversial stop-and-frisk program, agreeing to remove more than a half-million names from a database of information collected during police stops of New Yorkers—largely black and Latino males.

The Bloomberg administration has been unwilling to back down from the program implementation, even in the face of withering criticism from civil rights groups. But court papers released yesterday revealed that the city voluntarily scaled back one significant part of its stop-and-frisk program by agreeing to purge the hundreds of thousands of names from the database.

The New York Police Department started the database in 1999 to compile and review information learned during millions of stop-and-frisk encounters, saying it would help investigators find potential suspects or witnesses to crime.

In 2010, a new state law forced the department to expunge from the database the names and addresses of people who were stopped but never charged with a crime or issued a summons. However, the law allowed the department to keep the information about stops that resulted in arrest or summons—about 565,000 since 2004.

But the New York Civil Liberties Union mounted a legal challenge to the department for keeping those names. That lawsuit resulted in the settlement that moved the NYPD to expunge the remaining names.

Christopher T. Dunn, the associate legal director of the NYCLU, said the settlement was important because it was so unusual for the city to retreat on any measure of the stop-and-frisk program.

“It starkly signals the city’s recognition that a key part of the stop-and-frisk program went too far,” he told the New York Times.

According to the settlement, within 90 days the city must delete “any remaining information that establishes the personal identity of an individual who has been stopped, questioned and/or frisked, including the name and address.”

The city is allowed to maintain other information regarding the circumstances of the stops.

Celeste Koeleveld, a senior lawyer for the city who is supervising its defense of stop-and-frisk, downplayed the significance of the settlement, claiming it was “a natural outgrowth” of the 2010 law. She said some of the information was already accessible to police officers through other databases.

“At the end of the day, it just didn’t make sense to continue this particular litigation,” she said.

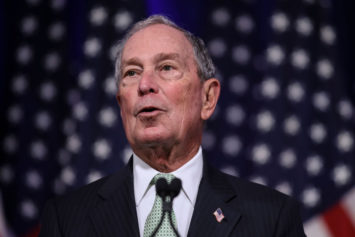

Mayor Michael Bloomberg, upset over two bills passed by the New York City Council curbing the power of the New York Police Department, angered many in June when he claimed that the police department stops too many white people and not enough minorities.

“I think we disproportionately stop whites too much and minorities too little,” the mayor said during his regular Friday morning WOR radio show with John Gambling. “It’s exactly the reverse of what they say. I don’t know where they went to school but they certainly didn’t take a math course. Or a logic course.”

The NYPD’s stop-and-frisk policy is the subject of a federal lawsuit brought by four men who claim they were stopped solely because of their race, along with millions of others stopped in the last decade.

A federal judge is currently deliberating the case and is expected to hand down a decision in the next few weeks determining whether to order reforms to the policy and establish the court’s own monitoring. City attorneys have argued that the stops were lawful and not based on race alone.

The NYPD has conducted about 5 million stop and frisks in the last decade, with more than 80 percent of those stopped being black or Hispanic, and arrests resulting less than 15 percent of the time.