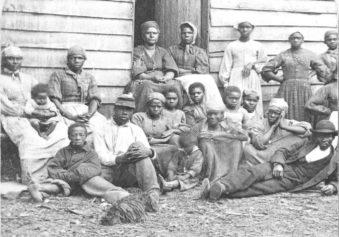

With more than 20 years of peonage research under her belt, historian and genealogist Antoinette Harrell has cemented herself as an expert on modern slavery in America. Her recent studies have led to the uncovering of painful truths, however, including numerous cases of African–Americans still living as slaves nearly 100 years after the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation.

Speaking with VICE, Harrell explained how years of research led to the discovery. She said it all started with the digging up of her own family’s records, during which she managed to track down Freedman contracts for the Harrell side of her family, who were sharecroppers. The Louisiana-native soon began helping others unearth their histories just as she did, but it was no easy task.

” … The only fact that seemed certain was that slavery ended with the passing of the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863,” she told VICE. “But even that turned out to be less than true.”

Harrell recalled the day a woman familiar with her work approached her and said, “Antoinette, I know a group of people who didn’t receive their freedom until the 1950’s.” Before she knew it, she was in contact with 20 folks who’d spent most of their lives working the fields at the nearby Waterford Plantation in St. Charles Parish, La. All had in some way become indebted to the plantation owner and were forbidden from leaving the property — a situation that left them living like modern-day slaves.

“At the end of the harvest, when they tried to settle up with the owner, they were always told they didn’t make it into the black and to try again next year,” Harrell explained. “Every passing year, the workers fell deeper and deeper in debt. Some of those folks were tied to that land into the 1960’s.”

Though several decades had passed, many of the workers were hesitant to share their stories because many of the same white families who owned the plantations also held political and economic power, she added. So, many of the cases went unreported for fear of repercussions.

Several months later, Harrell would meet a woman named Mae Louise Walls Miller who didn’t receive her freedom until 1963. Miller, who grew up poor, said her family didn’t have a TV at the time and assumed everyone lived the same way she did. As a teen, she and her mother suffered rape and violence at the hands of the plantation owner. She had finally had enough and at 14, decided to escape to the woods. She and her relatives were eventually taken in by a white family.

Harrell noted that stories like Miller’s were fairly common for racial and ethnic minorities in the Deep South. A vast majority of 20th-century slaves were of African descent, however.

“Do I believe Mae’s family was the last to be freed? No,” she told VICE. “Slavery will continue to redefine itself for African Americans for years to come. The school to prison pipeline and private penitentiaries are just a few of the new ways to guarantee that black people provide free labor for the system at large.”

“If we don’t investigate and bring to light how slavery quietly continued, it could happen again.”