A new report from the People’s Policy Project argues that class and racial disparities play a role in mass incarceration, but concludes that class plays an overriding role. (Photo: PBS)

What role does race play in mass incarceration? With 5 percent of the world’s population and one-quarter of its prisoners, the United States is the world leader in prisons, incarcerating 2.3 million people — more than any other country in terms of both absolute numbers and the percentage of the population. The racially disproportionate impact of mass incarceration in America is self-evident, as African-Americans are incarcerated at a rate 5.1 times greater than whites, and 1 in every 10 Black men in his 30s is in jail or prison on any given day. Some scholars, writers, advocates and other observers have pointed to a history of slavery and Jim Crow that has criminalized and exploited Black people to this day.

A new report takes a different approach in explaining the nature of the racial disparities in the imprisonment of Americans. The report (pdf) presented by the People’s Policy Project, notes that left-leaning analyses of mass incarceration interpret the institution as either a racist system stemming from segregation or a capitalist system designed to control the poor, and concludes that the backstory behind prisons is a matter of race and class, with class as the predominant factor at play.

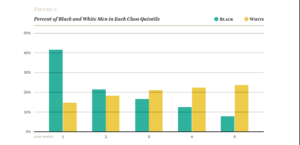

Figure 1 (Source: People’s Policy Project)

Nathaniel Lewis, the author of the report, makes his case for a class-based explanation for mass incarceration by examining four issues: 1) whether men 24-34 years old have ever been to jail or prison; 2) whether men are jailed after arrest; 3) whether men have spent more than a month behind bars; and 4) whether men have spent more than a year incarcerated. As to the first three issues, Lewis concluded that class has a significant impact. Race, however, has a significant effect on the fourth (Figure 1), according to his analysis based on data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health.

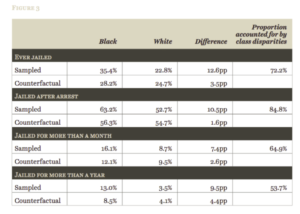

Figure 2 (Source: People’s Policy Project)

According to the analysis, the primary reason for the gap in Black and white incarceration rates appears to be the difference in class dynamics for the two racial groups, or how people are distributed across the socioeconomic spectrum. While 42 percent of Black men are in the lowest class quintile group, 15 percent of white men fall in the lowest class. In addition, 24 percent of white men were in the highest class group, as opposed to 8 percent of Black men (Figure 2).

Figure 3 (Source: People’s Policy Project)

The author then used a counterfactual scenario to factor out the class differences between white and Black men, and determine the percentage of the racial mass incarceration gap that is due to class disparities (Figure 3). The proportion of the Black-white incarceration gap attributed to class disparities falls between 53.7 percent and 84.8 percent. In three of the four criminal justice outcomes the report outlines, race in and of itself makes no statistically significant difference. Even as the report highlights the importance of class in mass incarceration, it acknowledges that even class in America is itself racialized, underscoring the intractability of institutional racism and the inextricable link between race and class. After all, the economic disadvantages of Black families are such that they would require two centuries to close the wealth gap with white families.

In its analysis, the People’s Policy Project straddles the line between two schools of thought regarding the cause of mass incarceration of Black people. On the one hand, there is the idea to which thinkers such as Michelle Alexander, author of “The New Jim Crow,” subscribe, which is that mass incarceration is race-based and designed to control Black people, stemming from a system that arose after the end of legal Jim Crow segregation.

As the Equal Justice Initiative articulated in a video, slavery did not end in 1865. Rather, the mythology of racial difference that justified the perpetuation of the institution has continued to the present day in terms of the racial profiling of Black men and boys, the presumption they are dangerous criminals, and how this translates into criminal justice policy and mass incarceration.

On the other hand, there is the concept promoted by Cedric Johnson and others that America pursues a project based on imprisoning poor men, which disproportionately ensnares Black men, who are much more likely to be of a lower socioeconomic status.

Overall, this study supports the view of Cedric Johnson of Jacobin magazine and others that while racial disparities remain, mass incarceration in the United States is primarily a system of locking up lower-class men — one which ends up disproportionately imprisoning black men, since they are far more likely to be lower class than white men. In his essay “The Panthers Can’t Save Us Now” Johnson argues for popular anti-capitalist politics rather than a left politics based on racial affinity and anti-racism, which in his view are susceptible to compromise and a watering down from elite brokers, philanthropies and bourgeois interests.

Johnson acknowledges that “blackness is still derogated but anti-black racism is not the principal determinant of material conditions and economic mobility for many African Americans,” he wrote in Jacobin magazine. Johnson believes that all forms of exploitation — whether racism, sexism, xenophobia, ethnic rivalry or segmented labor markets — all work against solidarity and to the benefit of capitalism. “Whether we are talking about antebellum slaves, immigrant strikebreakers, or undocumented migrant workers, it is clear that exclusion is often deployed to advance exploitation on terms that are most favorable to investor class interests,” Johnson said.

Suggesting solutions, the report embraces economic policy, which could mean wealth redistribution, full employment, a complete welfare state and guaranteed income, and universal free college. “Understanding this reality is important for policymakers interested in rolling back the American carceral state. While racial discrimination and bias are clearly present in various aspects of the criminal justice system, eliminating that bias will not effectively reduce the racial disparities of mass incarceration,” Lewis wrote. “This is because these disparities are primarily driven by our racialized class system. Therefore, the most effective criminal justice reform may be an egalitarian economic program aimed at flattening the material differences between the classes.”

Given the role of role of slavery, Jim Crow and present-day institutional racism in allowing white people to amass inheritable wealth over centuries — and the economic exploitation of Black people through enslavement, sharecropping, the convict lease system, redlining, subprime mortgages and other forms of institutional racism — reparations are a foreseeable policy prescription, though the report does not provide specifics. Further, Johnson, whose view Lewis supports, criticizes Ta-Nehisi Coates and others who support reparations, dismissing the demand as “a form of moralism that evokes past injury to address contemporary inequality,” and a “political dead letter, incapable of ever addressing institutional power in any effective way.”

Whether mass incarceration is primarily a matter of the New Jim Crow, class warfare or both, it is clear that America has a racial class system, and Black people are the ones filling up the prisons. Any solutions to the problem must acknowledge this reality.