A new report from the Partnership for Southern Equity (PSE) challenges the notion that all Black people in Atlanta are sharing in the local and regional economy. The report — “Growing the Future: The Case for Economic Inclusion in Metro Atlanta” — found that while the Atlanta area is becoming more diverse and future competitiveness depends on an inclusive economy, the reality is that poverty and inequality are in abundance.

Partnership for Southern Equity

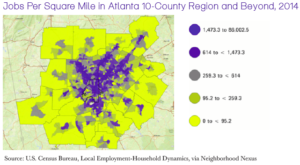

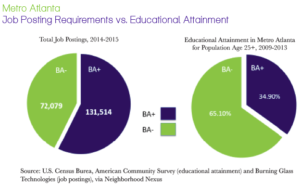

Despite the economic growth in Atlanta, its poorest residents do not have access to opportunity or upward mobility. The city was ranked highest in income inequality in 2012, and has had a history of communities experiencing isolation based on race and income. And depending on where Atlantans live, there is a lack of access to jobs, and too many jobs in which too many people lack the education for those jobs.

“I definitely think it is the mecca. Atlanta’s ideal in itself makes it the mecca in terms of the history of Maynard Jackson and what he did for economic opportunity, and making millionaires through the Hartsfield-Atlanta Airport,” Nathaniel Smith, Founder and Chief Equity Officer/CEO of PSE, told Atlanta Black Star.

Smith also noted “the legacy of Dr. King and Ralph David Albernathy and others who made Atlanta the logistical hub, the Atlanta University Center with DuBois and Howard Thurman, and the Black intellectuals who decided to stay in Atlanta. So there are many reasons why Atlanta still is the Black mecca, but the challenge is Atlanta has a caste system where a significant portion are doing well. It is important to see wealth and opulence, but if they are not fully positioned to benefit from that then we are more hypocritical than those who are oppressing us.”

Partnership for Southern Equity

PSE reported that Atlanta is a story of division based on race and class. According to data from The Annie E. Casey Foundation, 20 percent of Black children live in low-poverty areas, while 94 percent of white children live in such areas. Further, PSE found that the city is divided by Interstate 20, with the wealthier white communities to the north of the interstate, and poorer Black neighborhoods to the south. In addition, 44.1 percent of the poor in suburban Atlanta live in areas with poverty rates of 20 percent and higher.

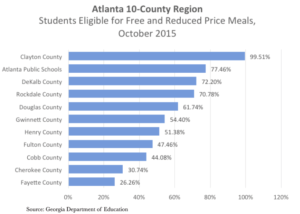

Throughout the counties in Metro Atlanta, the disparities are evident. For example, south DeKalb County suffers from limited access to transportation, a lack of quality education and a lack of job mobility. In North Douglas County, which has the highest concentration of poverty, home ownership and home values are low. In north Clayton County, high-income, educated families send their children to private school or have left the area, while residents of Atlanta public housing have moved in, resulting in a public school system almost entirely of low-income children. In contrast, gentrification in the Old Fourth Ward of Atlanta has resulted in the displacement and departure of low-income residents, while southeast Atlanta is experiencing an economic divide, with lower-income Black people living alongside those at the top socioeconomic levels.

Partnership for Southern Equity

“We’re leaving a lot of talent behind, and a lot of poor kids have a lot to offer the Black community and Metro Atlanta, and we’re leaving them behind. I would say as a native of Atlanta that Atlanta is an ideal in terms of the millionaires created,” Smith argued. “Yet still, we are losing our way and we are leaving people behind, and nobody is talking about it.”

The PSE report emphasizes the need for economic inclusion, which it defines as “Increasing equity in the distribution of income, wealth building, employment, and entrepreneurial opportunities for vulnerable populations,” and a region where “all residents – regardless of their race/ethnicity and nativity, gender, or neighborhood of residence – are fully able to participate in the region’s economic vitality, contribute to the region’s readiness for the future, and connect to the region’s assets and resources.”

“Economic inclusion is really about creating an economic system that is both lucrative and just. It is also about creating the conditions where all people contribute and prosper in it,” Smith said. “And all the barriers that are in place to keep people from maximizing their full potential, including structural racism are removed, and we all have a chance to participate and prosper,” he added. Think of economic inclusion as “no child left behind,” not in rhetoric, but in reality.

Moreover, economic inequality is costly, not only to the poor but to everyone, and Atlanta is paying the price. According to PSE, full employment in the Atlanta area would have meant $23.6 billion added to the local economy last year. That translates into 283,500 more people employed, 175,000 fewer people living in poverty, and $4.5 billion in additional tax revenue. Likewise, the U.S. economy as a whole would grow by over $5 trillion each year if racial disparities in income were eliminated, while closing the achievement gap in the performance of Black and Latino students versus their white counterparts would increase U.S. GDP from $310 to $525 billion.

Making the case for an economic inclusion agenda in Metro Atlanta, PSE recommends increased financial education and access to safe and affordable financial products; more inclusive employment programs; programs that facilitate business development and entrepreneurship among the poor and people of color; access to quality pre-K-12 education, and models that prepare people for high-demand jobs. Further, community leadership and collaborative partnerships between organizations and the community can play a crucial role as well.

“The current system is not only wrong but it is inefficient,” Smith said of the inequity that currently pervades the economy in Atlanta. “We’re becoming a more diverse region, and people of color are becoming a majority. The workforce is going to be very different years from now, and many people are being left behind in the economy,” he added.

The economic model of the South was built on the backs of the enslaved, Smith noted, arguing that now, the economic system that has used racism and oppression as its cornerstone has to change.

“The writing is on the wall,” Smith said.