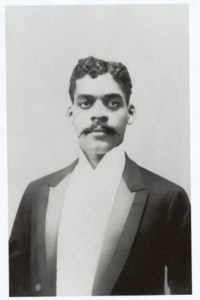

Arthur A. Schomburg

January 24 was the birthday of Arturo “Arthur” Alfonso Schomburg (1874-1938), the Black historian and critical figure of the Harlem Renaissance, and a Black liberation activist and writer who shone the spotlight on the legacy of people of African descent. Schomburg helped inspire African-Americans, Afro-Latinos and others throughout the diaspora.

Born in Puerto Rico, Schomburg migrated to New York in 1891 and was active in the Puerto Rican and Cuban liberation movements. Once told by a fifth-grade teacher that Black people had no history or accomplishments, he dedicated his life to highlighting the achievements of the African diaspora.

Following the U.S. takeover of Puerto Rico and the end of the Cuban revolution, Schomburg turned his attention to the Black community in the U.S. During his visits to the South, he was exposed to Jim Crow segregation and the conditions that Black people faced, including lynchings, race riots and the disenfranchisement of Black voters.

In 1911, he turned a Cuban and Puerto Rican lodge into a Prince Hall lodge, renaming it in honor of Black freemasons, and founded the Negro Society for Historical Research. In 1922 he was elected president of the American Negro Academy, which was the foremost organization dedicated to research in Black history.

The scholar also forged friendships with some of the greatest Black minds of the day, such as W.E.B. DuBois, Alain Locke and James Weldon Johnson, who encouraged him to compile a seminal bibliography of Black poets known as the 1915 “Bibliographical Checklist of American Negro Poetry.”

An avid collector of literature, art and other material on Africa and the African Diaspora, Schomburg had amassed over 10,000 items, which would become accessible to the writers of the Harlem Renaissance. This came at a time when millions of Black people from the South, the Caribbean and Africa moved to Harlem, which was called the Black capital of America.

In 1926, the Harlem branch of the New York Public Library purchased his collection with a $10,000 grant from the Carnegie Corporation. Known as the Schomburg Collection of Negro Literature and Art, and later known as the Arthur Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, he served as curator until his death. The May 1925 edition of Opportunity described the purpose of the new collection: “To preserve the historical records of the race; to arouse the race consciousness and race pride; to inspire art students [and] to give information to everyone about the Negro.”

Schomburg’s materials were impressive, containing, according to Howard Dodson, “over five thousand books, three thousand manuscripts, two thousand etchings and portraits, and several thousand pamphlets.” This vast collection included the works of Benjamin Banneker, Paul Lawrence Dunbar and Frederick Douglass, the letters of Toussaint L’Ouverture, the poetry of Phillis Wheatley, Alexander Pushkin, Juan Latino and others.

Arthur Schomburg was an intellectual visionary who was far ahead of is time. Over 100 years ago, he advocated for the incorporation of Black history courses in the American educational system. In a speech to Black educators at Cheyney University, Schomburg said teachers should “include the practical history of the Negro race from the dawn of civilization to the present time” in the existing curriculum. He later added that “it matters not whether [black history] comes from the cloisters of the university or from the rank and file of the fields.”

Just as Carter G. Woodson and W.E.B. DuBois were encouraging Black minds to take up the mantle of African-American history, so too did Schomburg inspire a new generation of Black scholars and writers. For example, his essay “The Negro Digs Up His Past” promoted African-American writers and inspired many Black people to begin to uncover their past. Further, he served as a mentor to people such as Dr. John Henrik Clarke, and was an invaluable resource to others such as DuBois, Locke and Charles S. Johnson. Upon his death, Opportunity magazine wrote the following on Schomburg: “To his people and to his generation he gave all of his energy, his vision, and the strength of his spirit, and more than this no man can give.”

The leading research center on Africa and the Diaspora, the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture of the New York Public Library now contains over 10 million items.