Some South Africans are calling for the removal of South African president Jacob Zuma. And perhaps he should go. But if he does, what happens next? Will the legacy of apartheid then be erased? Will the white South Africans who called for Zuma’s ouster fight against white supremacy and structural inequality against Black people?

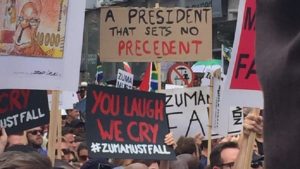

Thousands of protesters have marched throughout South Africa, in response to the leader removing two finance ministers and further eroding confidence in the economy, according to the BBC.

The protests come in the wake of student protests over proposed university tuition fee hikes and claims of government corruption, as the governing African National Congress undergoes a political struggle over succession. Activists on social media have employed the hashtag #ZumaMustFall, a modification of the #FeesMustFall hashtag used by university students, and #RhodesMustFall, which centered around demands for the removal of British racist and colonialist Cecil Rhodes from the University of Cape Town.

Thousands of Capetonians march under #ZumaMustFall banner https://t.co/7vTdIrHwgx pic.twitter.com/Gabx0UGqH0

— S.A. Politics (@SAPoliticsRR) December 16, 2015

As warned, #ZumaMustFall march dominated by whites. Black radicals watch their #MustFall be reduced to a catchphrase pic.twitter.com/2n2xAERJQ9

— Rhodes Must Fall (@RhodesMustFall) December 16, 2015

Black people still waiting outside the white owned and controlled economy…. pic.twitter.com/VKjnduRHXL

— Sentletse (@Sentletse) December 16, 2015

There are natives who say there nothing wrong with the apartheid flag being waved around in our faces! pic.twitter.com/X783ifxrAH

— Sentletse (@Sentletse) December 16, 2015

So from #ZumaMustFall to #BringBackApartheid …ja nhe ?… pic.twitter.com/TdIWBkXpwI

— Ndumiso Lindi (@roosta27) December 16, 2015

Levels #ZumaMustFall pic.twitter.com/k8K05142sW

— Rhodes Must Fall (@RhodesMustFall) December 16, 2015

Although some of the coverage of the protests are emphasizing a multiracial component to the protests against Zuma, even invoking the name of Nelson Mandela in some cases, there are indications that the protests are dominated by white interests. A component of the opposition speaks more to an issue of white privilege, and the prospect of whites losing even a little bit of their privilege in South Africa. The specter of some whites waving apartheid-era South African flags is a prime example. Although Zuma is somehow being painted as the enemy, for all of the criticisms lodged against him, white supremacy remains a problem in this country. South Africa has a majority Black citizenship, and yet only 3 percent of the economy is Black-owned. A South African Department of Trade and Industry survey also found that Black graduates are three times more likely to be unemployed than their white peers.

I refused to sign the #Zumamustfall petition because it was initiated by white capital which called #Marikana workers criminals…

— Julius Sello Malema (@Julius_S_Malema) December 14, 2015

The genuine revolution against the #ANC and #Zuma will be black led and will ultimately overthrow white monopoly capital and transfer land

— Julius Sello Malema (@Julius_S_Malema) December 14, 2015

While Zuma, like any leader, should be held responsible for his record, it is hard to believe that he can be blamed for a long legacy of apartheid and white rule, in a country that emerged from white political power only 21 years ago.

“What is notable in these marches is that they are organized by a few groups of people who seem not to be interested about fiscal policies of the country,” ANC spokesperson Zizi Kodwa told News24. “They’ve got other interests, such as regime change, and they harbor racist hatred.”

Kodwa argued that those who marched recently pretend to be fighting for democracy, yet could not co-exist in a democratic, non-racial South Africa.

Meanwhile, a petition on Change.org is requesting that the European Union recognize the right of White South Africans, Namibians and Zimbabweans to return to Europe. “The idea that white South Africans have the right to return to Europe is based in the concept of indigenous rights and self determination,” reads the petition. “The white South African population currently faces ethnic cleansing and persecutions at the hands of the ANC government, the EFF, and various individual anti-white aggressors…. Many white South Africans today live in poverty and squalor as a consequence of the ANC government’s Black Economic Empowerment policy which shuts whites out of the [labor] pool.”

“As it currently stands, many white South Africans who try to apply for citizenship to European countries such as the Netherlands and UK are rejected. Many of these white South Africans seeking citizenship are direct descendants of the very same European nations that reject them,” the petition added.

As Kelly-Jo Bluen wrote in BusinessDay, the white response to #ZumaMustFall reflects “last-straw-end-of-days-apartheid-nostalgia” and a narrow, “myopic” focus on their interests, as whites absolve themselves of any responsibility for the nation’s malaise. In Bluen’s view, much of the white commentary ranges “from explicit racism to the curated dog-whistle racism that often characterises white narratives about black governance.” In the process, she argues, white South Africans focus solely on Zuma and the specter of Black corruption, yet ignore the role of white supremacy in the society and the economy, and the refusal of whites to relinquish their “unsurpassed privilege.” White South Africans, she argues, are able to pretend that social and economic exclusion of Blacks, and the inequality of wealth and land ownership are not the causes of the problems in the South African economy.

Under his tenure, Zuma has accomplished a number of things, such as freezing tuition fee increases in South African universities. He has reached out to foreign nationals and has given them access to the government in the wake of xenophobic attacks. In an address to the African Union, he said that Africans must resist external regime change:

“Through the AU, the peoples of Africa must reject any idea from outside the continent which seeks to foster an agenda of regime change.”

In addition, Zuma deployed troops to the Democratic Republic of the Congo to fight rebels and help bring stability to the nation. And policies of affirmative action and Black empowerment have made some whites feel as if they are victims of racism. Two decades after apartheid, racism against Blacks remains and racial tensions persist. Blacks are still fighting to reclaim land taken under apartheid, a system that branded them inferior, kept them politically disenfranhchised, economically suppressed, and prevented them from owning land.

The real enemy is not Zuma, even if the South African public decides he must go. But if a system remains in place that keeps the majority Black population down, then it does not matter who is in power.

White people at the #ZumaMustFall march in Braam.But dololo attendance when we protest against structural inequality pic.twitter.com/gnN1JARn5j

— Simamkele Dlakavu (@simamkeleD) December 16, 2015

Spot the difference – #FeesMustFall versus #ZumaMustFall pic.twitter.com/40Pb5gvcEw

— Vuyisa Qabaka (@vuyisaq) December 16, 2015