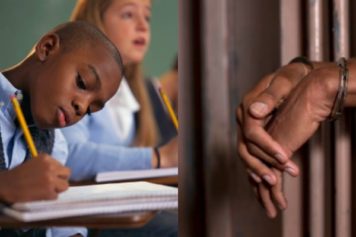

There is no questioning the importance of having a quality education, and the growing educational achievement gap in the U.S. makes it painfully obvious that not every child is getting access to that kind of valuable learning experience.

While many people agree it’s troubling that some schools breed students for success while others can barely save their pupils from the school-to-prison pipeline, nobody can seem to settle on exactly what’s causing such a disparity.

While theories are constantly being discussed and analyzed, one renowned economist decided there was only one way to really start figuring out how to get every public school across the nation to prosper—start testing different theories in the real world.

Harvard University economics professor Roland G. Fryer Jr. sparked a lot of controversy with such an idea, but his past work has been so outstanding that it made him the first Black person to win the prestigious John Bates Clark medal—an award given to the most promising American economist under the age of 40.

Fryer started the experiment by first examining nearly 40 New York City charter schools that were not subjected to the type of universal standards that public schools have to adhere to.

This allowed him and his colleague, Will Dobbie of Princeton University, to observe a variety of different educational strategies and environments and document how it impacted student success.

After the observations were over, Fryer uncovered what he believed would be the five “tenets” of student achievement.

These “tenets” were, “frequent teacher feedback, the use of data to guide instruction, frequent and high-quality tutoring, extended school day and year and a culture of high expectations,” Newsweek reports.

This is where much of today’s modern experiments end when it comes to education.

There are a plethora of studies that take note of how other schools obtain success, but very few take things a step further by figuring out if those same tactics will be effective on a larger, broader scale.

“So, in 2010, [Fryer] began working with Houston school superintendent Terry Geier to implement a program based on Fryer and Debbie’s five tenets,” Newsweek reports. “The program, deemed ‘Apollo 20,’ after Houston’s historic role in the U.S. space program, targeted 20 of the city’s worst performing schools, including four that were slated to close before Fryer stepped in.”

For that reason, some considered Fryer to be a bit of a hero. It was his program that was keeping a vast collection of students in the same halls they had already become so familiar with.

Others, however, focused on the negative implications of the study. In order to enact the new strategies that had made other schools so successful, many current principals were let go.

Not to mention, the school reform process would be expensive and funded by public resources.

Either way, Fryer was allowed to move forward.

The changes were implemented but the results were not astonishing.

“According to a follow-up report done by Fryer himself, the results have been mixed,” Newsweek adds. “While students made significant gains in math, reading remained stagnant, highlighting the problem of trying to replicate charter school success stories on a larger scale.”

His results weren’t exactly what he hoped for, but they were important findings nonetheless.

It proved that the very idea of using charter school success as a blueprint for public schools was flawed.

Despite the lack of significant changes in reading scores, many schools across the country have started to adopt their own version s of the “Apollo 20” program with some seeing impressive results.

The decision to actually implement his findings in public schools is something that some might refer to as a “passion project” for the renowned economist who knows a lot about the racial achievement gap plaguing education.

Fryer grew up in what some had described as a “troubled home,” and that has given him a unique perspective on dealing with disparities and inequality.

So while he may not have actually found the answer to what really makes schools successful, he did manage to revolutionize the way such research may be approached in the future.