The Falcon School District 49, the Colorado Springs district, entered into a “comprehensive settlement agreement” to resolve complaints about the district’s response to racial harassment and discrimination in schools, according to a DOJ press release lauding the settlement.

The county that includes district 49, El Paso County, is overwhelmingly white. According to the 2010 Census data, the county was 84 percent white and just 6.8 percent Black.

Dana Palmer, former chair of the District Accountability and Advisory Committee (DAAC) for the school district and the Full Accountability chair for Falcon High School, said the new agreement is like a “Band-Aid on a wound that needs a tourniquet.”

“One of the biggest problems that is continuing in D-49 for staff members, for parents and for students is that we don’t feel safe in reporting [incidents of racism/discrimination],” Palmer told Atlanta Blackstar in an interview.

Palmer said that teachers also feel that there isn’t a safe place to go and that they’d rather resign than confront the issue. Parents either tough it out until their children graduate or they pull their children out of the school district.

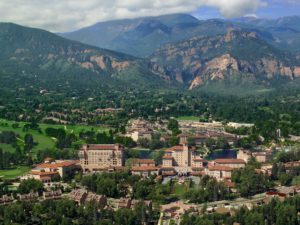

The experiences of Black students and parents in Colorado Springs illustrate the difficulties Black families can face in overwhelmingly white towns and school districts, where feelings of distance, alienation and differential treatment become as common as the crowds at the Friday night football games.

This is the second time in under five years that this district has agreed to a settlement with the DOJ. In 2010, the school district and the Justice Department reached an agreement, but not enough was done to satisfy the DOJ nor the Black community.

The school district failed several times to supply an adequate compliance report to the DOJ. Since the initial agreement in 2010, the DOJ’s “review of the events that have transpired during those four years make clear that the agreement was not fully complied with,” according to an April 2014 letter from the DOJ to the district’s attorney, W. Kelly Dude, that was obtained by Atlanta Blackstar.

The letter goes on to highlight multiple incidents where the terms of the 2010 settlement agreement were either ignored or just halfway met.

The compliance reports sent to the DOJ in 2010 “were deficient in numerous aspects.”

In March 2010, the school district didn’t supply the required semester report, or all the complaints of harassment/ discrimination. Out of the complaints it did report, the grade level, sex and race/ethnicity of the parties involved were not reported.

The July 31, 2010, compliance report was also incomplete; there were no semester and no discrimination/ harassment reports.

The first nearly complete report the school district submitted was received by the DOJ on March 11, 2011, and it still had no information regarding the sex and race/ethnicity of the parties involved in incidents of harassment/ discrimination. There was also no report of any training provided to students.

The inadequate reporting continued through January 2014. The information for the 2010-11 school year wasn’t submitted until Feb. 28, 2013. It and the compliance reports for October 2013 and January 2014 still “suffers from deficiencies similar to those [the DOJ has] identified throughout the course of the agreement,” the letter reads.

As the list of “deficiencies” continued to grow, the Black community expected some kind of action after the school district failed to meet the agreement with the DOJ. Instead of punishing the school district, the DOJ entered into another settlement agreement.

Henry Allen, president of the Colorado Springs chapter of the NAACP and former board member of the Falcon School District 49, doesn’t believe a new agreement is enough to change the school district.

“I have a problem with them extending [the agreement],” Allen said in a phone interview with Atlanta Blackstar. “I was concerned about [the DOJ] allowing District 49 to continue this type of behavior… District 49 is still acting out in the same way that it has; it will continue to do that. It has a history of doing that.”

Education on every level is needed to create an actual change in the culture of the school district, according to Palmer.

“There needs to be someone in these schools working with the students, working with administration, and that’s part of the issue with our concerns about reporting instances,” she said. “Because the staff are not trained on how to deal with it. Sure I can file a report if I’m an admin member in a building, but that doesn’t teach me or my peers or my subordinates how to deal with the current issue, let alone the issue that’s moving forward.”

The Rev. Promise Lee, who had three children in Falcon School District 49, along with 30 other concerned parents said their children were frequent targets of racist remarks back in 2008, The Gazette reported. They held a news conference in front of the district’s headquarters and said that the district’s leaders had “turned a deaf ear to racism.”

“The racial discrimination problems in D 49 are systemic,” Lee told Atlanta Blackstar via text message. “That is not to say that every employee, volunteer or parent of D 49 is a racist. But one would be a fool to close their eyes and deny the fact that racism is alive and well whether intentional or ignorant in District 49.”

A Black teacher, for example, had been consistently referred to by students and staff as “that colored teacher.”

There have been multiple occasions where white students used racial epithets toward Black students. In one case, four Blacks received counseling after the incident, but nothing was done to the student who said the epithet, according to The Gazette.

These types of complaints are why there was a need for significant change in leadership and policy for District 49.

In 2013, Peter Hilts became the chief education officer for District 49 and sought out the new agreement with the DOJ to resolve the issues of cultural insensitivity.

Hilts was a senior leader in Colorado’s school choice movement and specialized in innovation initiatives, organizational reform and strategic planning for schools and districts before he took the CEO job with District 49.

After there was significant turnover in leadership at the board and executive levels, Hilts and other chief members sought to “re-establish and re-connect” with the DOJ.

Despite the new leadership, the school district continued to fall short of the expectations of the Black community and the DOJ.

“The office acknowledges the District’s position that its failure to comply with the Agreement was influenced by high turnover in personnel and other changes within the District,” the aforementioned letter reads. “While we are sympathetic to the challenges the District has faced, the fact remains that we do not have an adequate basis for concluding that the District has taken sufficient steps to remedy the concerns that prompted the Agreement in the first place.”

“There were members of our community that felt that their concerns had not been adequately resolved,” Hilts said. “It isn’t that the district was ignoring or dismissive of any of those concerns, but when you have members of the community that feel that their concerns are not properly resolved one of their avenues is to raise that.”

Instead of waiting until the initial agreement with the DOJ expired, the school district proposed a modified agreement to the DOJ to avoid potential punishment for failing to comply with the first one.

“We initiated that process of coming to a new agreement, and I’m glad that we did,” Hilts said. “I believe we’ve got an agreement that is going to help make sure we’re a district where every student, every parent, every staff member is absolutely welcomed and affirmed; and feels welcomed and feels valued.”

The new settlement agreement with the Colorado school district to address racial harassment and discrimination specifically details that the district agrees to revise its policies and procedures on harassment and discrimination; maintain adequate records of all incidents of racial harassment and discrimination; analyze incidents of racial harassment and discrimination to ensure that all incidents are properly identified, investigated and resolved.

The district must train staff in preventing and responding to harassment and discrimination, and provide training to students to prevent and address harassment and discrimination.

It must include restorative justice techniques and positive behavior interventions and supports in the district’s disciplinary responses to incidents of harassment and discrimination, and hire a consultant to identify any additional measures the district should take to effectively address, prevent and respond to harassment and discrimination.

The school district has been working with Dr. Louis Fletcher, the coordinator of cultural capacity. Fletcher says his role isn’t to be a median between the school district and the Justice Department, but more so a guide or mentor to administrators.

Fletcher says he’s building cultural capacity in the district so that the teachers and administrators know how to do things instead of depending on finding someone else to call. He has been teaching them how to approach situations and how to understand cultural sensitivity.

“It does no good for me to go out and put out fires, so to speak, and have them stand by passively,” he says.

“We’re introducing an overarching cultural curriculum that the teachers, administrators and district administrators, like myself, would partake in,” Fletcher says. “After that, we’re going to start to implement curriculum for the students.”

Fletcher says that the curriculum isn’t deficient, but his job is to identify what may be lacking or is being overlooked. The curriculum, however, needs to recognize the integrative nature of understanding and respecting all of the cultures within the district.

Fletcher says that he’s integrating the curriculum from the Southern Poverty Law Center’s Teaching Tolerance into the school’s existing curriculum.

According to Fletcher, he and the district are doing more than what’s necessary to satisfy their agreement with the Justice Department. In addition to his weekly reports and the required training, they’ve already started having interventions with teachers, administrators and students. The district is implementing restorative justice to reduce the number of suspensions and keep the students in school.

He also took it upon himself to review every policy in the district and the entire student code of conduct to determine what recommendations might be needed for change. He is working with the District Accountability Committee and talking to parents to determine what changes should be made to the conduct policy to better reflect the change they are trying to make.

Hilts says that the school district is “extraordinarily enthusiastic” about having a leader like Fletcher working with them. He says that Fletcher is helping them reach their aspirations of “being the best.”

The sentiment isn’t mirrored by Allen and Palmer, who both say that Fletcher’s position was created as a “smokescreen.”

“Our Chief Business Officer Brett Ridgway made the comment to budget committee members that it was just to avoid legal action from the DOJ,” Palmer told Atlanta Blackstar.

The school district hasn’t received a complaint since 2010, according to Hilts.

“We’re well beyond that phase of active complaint, but we’re still committed to meeting the highest standard,” he said.

The settlement agreement between the school district and the DOJ will run through 2017.

“We applaud the Falcon School District 49 for working cooperatively with the Department of Justice to resolve this matter and ensure that all students can attend school without fear of harassment or discrimination from their peers,” Molly Moran, acting assistant attorney general for the Civil Rights Division, said in the press release.

Ultimately, it’s the Black students and parents being affected by the decisions that the DOJ and Falcon School District 49 make, and the agreements have exhausted them. Allen, Palmer and Lee aren’t expecting anything different to come out of the newest agreement with the DOJ.

“We’re still in the same boat,” Palmer said. “The only difference is now more paperwork is required to try and prove we’re compliant.”