On June 20, two days after the death of baseball icon Willie Mays, also known as the “Say Hey Kid,” Major League Baseball hosted its first-ever game at the historic Rickwood Field in Birmingham, Alabama, in honor of Mays and other Negro Leagues players who left an indelible mark on the sport. The game was dubbed “A Tribute to the Negro Leagues.”

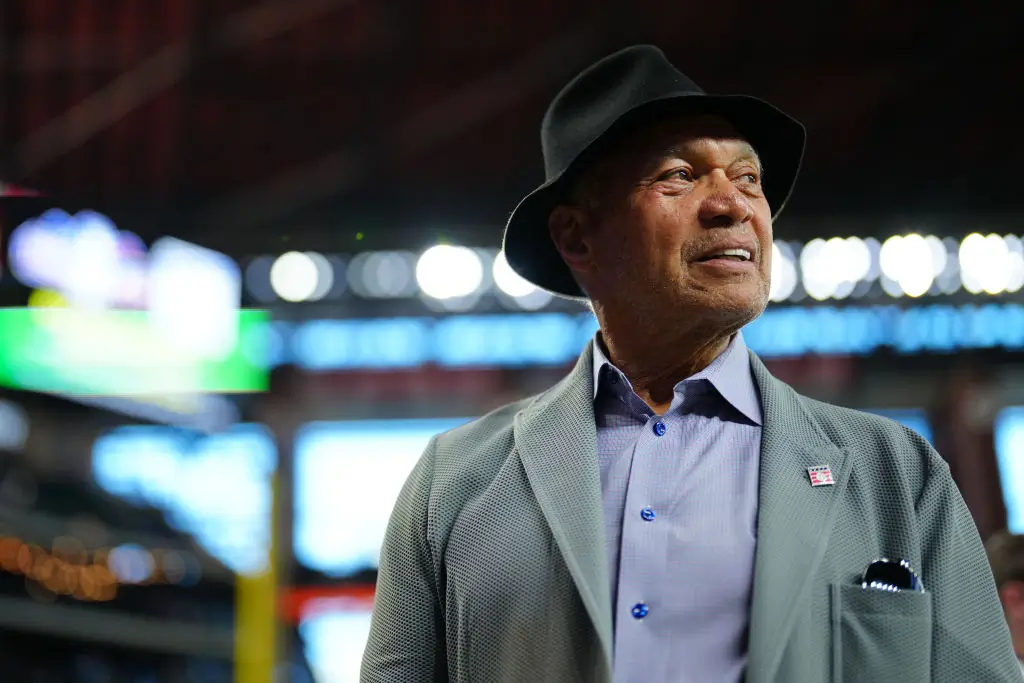

Baseball Hall of Famer Reggie Jackson joined the Fox Sports broadcast, where he was asked by former MLB star Alex Rodriguez about his emotional state as he returned to where he once played in the mid-1960s.

Jackson proceeded to share raw, painful memories of the racism he experienced during his time with the Birmingham A’s in 1967.

“Coming back here is not easy. The racism when I played here, the difficulty of going through different places where we traveled,” Jackson told Rodriguez. “Fortunately, I had a manager and I had players on the team that helped me get through it, but I wouldn’t wish it on anybody.

Jackson continued to share stories of the hatred he faced, recalling, “I said, ‘You know, I would never want to do it again.’ I walked into restaurants, and they would point at me and say, ‘The n—ger can’t eat here.’ I would go to a hotel, and they say, ‘The n—er can’t stay here.’ We went to [then-Athletics owner and Ensley, Alabama, native] Charlie Finley’s country club for a welcome home dinner. And they pointed me out with the N-word. ‘He can’t come in here.’ Finley marched the whole team out.”

Fighting tears, Jackson revealed that he would sleep on his teammate Joe Rudi’s couch for weeks at a time until racism forced him out.

“Joe and Sharon Rudi, I slept on their couch three, four nights a week for about a month and a half. Finally, they were threatened that they would burn the apartment complex down unless I got out. I wouldn’t wish that on anybody,” said Jackson.

Jackson thanked his teammates for having his back through such a tumultuous time, saying that if it weren’t for them, he would reacted in a way that could have ended badly for him.

“I would have never made it,” said Jackson. “I was too physically violent. I was ready to physically fight. I’d have got killed here because I’d have beat someone’s ass, and then you’d just saw me in an oak tree somewhere.”

Jackson’s story sheds light on baseball’s complicated history. A system of white supremacy ruled the sports for decades. Black athletes were prevented from playing alongside their white counterparts until Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in 1947.

For years, the achievements of Negro Leagues players were not recognized by the MLB. It was not until May 2024 that the league reversed course and declared that Negro League statistics would be officially added to MLB records.

“We are proud that the official historical record now includes the players of the Negro Leagues,” Commissioner Rob Manfred said at the time. “This initiative is focused on ensuring that future generations of fans have access to the statistics and milestones of all those who made the Negro Leagues possible. Their accomplishments on the field will be a gateway to broader learning about this triumph in American history and the path that led to Jackie Robinson’s 1947 Dodger debut.”

“There are people who want to romanticize Jim Crow. ‘It was a different time’ is not an excuse,” one person wrote in response to Jackson’s words on X.

“Thank you for sharing your experience Mr. Jackson. American needs to hear your story,” a social media user wrote.

Others took issue with the censorship of video replays of Jackson’s remarks.

“You shouldn’t have censored Reggie Jackson,” someone pointed out on social media.

“Why did you bleep his words? That’s what he was called by Whites. Don’t sanitize how it was to be Black in the Jim Crow South. Shame,” another person wrote.

It’s not the first time that Jackson, who finished his 21-year MLB career with 563 homers and five World Series titles, has spoken of his experiences with racism. He has alleged it played a role in the Mets’ decision to pass on him with the No. 1 pick in the 1966 MLB draft in favor of Steve Chilcott, a white player who never reached the major leagues.

Jackson has publicly spoken out about the racism he’s faced over the years. “Race is always on my mind, even today,” Jackson told Salon in 2013. “If you’re a minority, it’s on your mind.”

In Jackson’s tell-all book, “Becoming Mr. October,” he suggested that racism factored into the New York Met’s decision to skip over him in the draft and instead choose Steve Chilcott, a white player. Chilcott failed to work his way from the minor leagues and never reached the majors.

In an excerpt from the book, which the New York Post released in October 2013, Jackson recalled a conversation he had with college baseball coach Bobby Winkles about the MLB Draft.

“A day or two before the draft, Bobby Winkles sat me down and told me, ‘You’re probably not gonna be the No. 1 pick. You’re dating a Mexican girl, and the Mets think you will be a problem,’” Jackson wrote. “‘They think you’ll be a social problem because you are dating out of your race.’” Jackson is Black and Hispanic. His grandmother was born in Puerto Rico, and his middle name is Martinez.

Rickwood Field is billed as America’s oldest ballpark. It served as the home of the Negro Leagues’ Black Barons. The Birmingham Barons, a minor league team, played games at the ballpark.

Barry Bonds, Willie Mays’ godson, and Ken Griffey Jr. were among the former MLB All-Stars who attended the special game.