Mary McLeod Bethune, education trailblazer and civil and women’s rights activist, is now honored among the statues at the U.S. Capitol’s National Statuary Hall, making history as the first Black image in the distinguished collection.

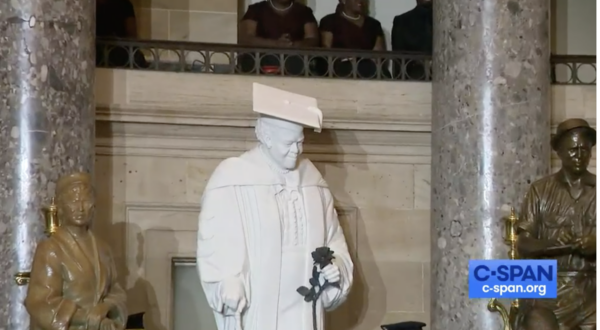

The 13-foot-long block of marble of Bethune, a daughter of formerly enslaved people, replaced a nearly 100-year-old bronze sculpture of Confederate General Edmund Kirby Smith on Wednesday, July 13, in Florida’s collection. Bethune statue wears a cap and gown and carries a black rose, representing the students that she served with her schools.

Each state has two statues in the collection that outgrew the hall in 1933. Bethune’s statue will be among former presidents, Native Indian chiefs and political leaders.

For Florida, Bethune’s figure joins John Gorrie, a physician, scientist and inventor of mechanical refrigeration. Florida gave the hall the Gorrie statue in 1914.

“That’s historic,” said Nilda Comas, the artist who created the sculpture. “It’s a once-in-a-lifetime occasion.”

There are figures of four other Black people in other parts of the Capitol: Martin Luther King Jr., Frederick Douglass, Sojourner Truth and Rosa Parks. Bethune is the co-founder of one of four historically Black colleges and universities in Florida.

She started the Daytona Literary and Industrial Training Institute for Negro Girls in 1904 with $1.50 teaching just five girls and her son. The school’s population grew to about 250 students before merging with Cookman Institute of Jacksonville, Florida, in 1923.

Bethune-Cookman University interim President Lawrence M. Drake II said the statute is a “pivotal moment” for the school Bethune cofounded. It took five years and fundraising of $1 million to bring the statue to fruition.

“It’s a special moment for this university, a special moment for America,” said Drake. “We have an opportunity to celebrate an enormously influential woman, someone that I think is still somewhat obscure to some people. There are people who don’t really know her. They may know her name or be aware of her, but this will offer the opportunity for them to look at her enormous impact, not just on Black America, but on the world.”

Bethune also founded the Mary McLeod Hospital and Training School for Nurses, the only school that served Black women at the time on the east coast. She was also one of the founders of the United Negro College Fund, a scholarship organization dedicated to minority students.

Bethune mobilized female voters after they gained the right to vote. Right after founding the new HBCU, she was elected president of the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs in 1923 and was the founding president of the National Council of Negro Women in 1935.

In a league of her own, Bethune also served as an adviser to American presidents. President Franklin Roosevelt appointed her director of Negro Affairs of the National Youth Administration, and she was reportedly a leader of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s unofficial “Black cabinet.” Bethune has been credited with helping African-Americans transition from the Republican to the Democrat Party.

“Dr. Bethune epitomizes the values we hold dear: industriousness, thirst for education, desire to build peace among people,” Democratic U.S. Rep. Kathy Castor from Florida said during the ceremony at the U.S. Capitol on Wednesday.

“She devoted her life to equal rights and service. Service, yes to presidents, but to students, women, her race, veterans and everyday Americans. We lift her up today at a time of competing ideologies to help heal and unify through her example because she also lived at a time of division, but determined to stand up to dissenting voices.”

Before sculpting the statue out of the same marble Michelangelo used for the world-renowned masterpiece of David more than 500 years ago, Comas visited the log cabin in Mayesville, South Carolina, where Bethune was born in 1875. She met Bethune’s family members, researched her at the Library of Congress, listened to her audio recordings and looked at nearly 300 pictures, reports show.

“I wasn’t familiar with her,” Comas said. “I didn’t know what she had done, so it was a beautiful journey, learning about her, getting to know her and coming up with ideas. I wanted a portrait that she would like, that would encompass her achievements.”

Comas has also created a bronze statue of Bethune at the Riverfront Esplanade Park in Daytona Beach. Locally, Bethune was not only an influential educator, but she also brought racial understanding to Daytona Beach. Reports show she was able to befriend white people to help with her school and other projects to help the Black community.

“If you’d let her get her toe in the door, it wouldn’t be long until her foot and her whole body was inside,” said 87-year-old Harold Lucas, whose father was an accountant and teacher at Daytona Literary and Industrial Training Institute for Negro Girls. “She was a very persistent person, and a very convincing person. She showed her sincerity and fought for what she believed in.”