More than 30 homeowners in the state of Washington’s capital have gone through the process of removing racially restrictive and unlawful language from covenants included in property paperwork after residents noticed a stipulation that bars non-white people from living in the neighborhood unless they are servants.

The original covenant for one woman’s Olympia, Washington, home, unchanged since 1951, clearly spells out who the mid-century neighborhood was intended for.

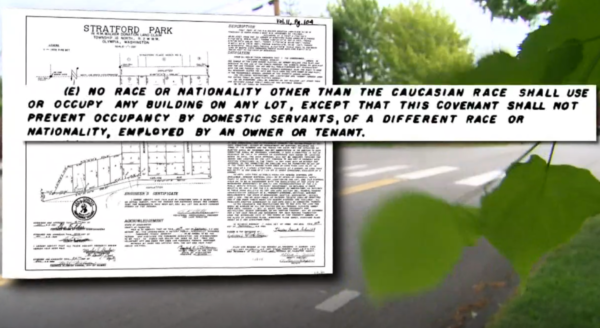

“No race or nationality other than the Caucasian race shall use or occupy any building on this lot, except that this covenant shall not prevent occupancy by domestic servants of a different race or nationality, employed by an owner or tenant,” the paperwork says.

Restrictive covenants, which are defined by Webster’s New World Dictionary as “a provision that restricts the action of a party to an agreement, as any covenant (unenforceable by law) seeking to prevent the sale of real estate to a member of a specified minority group,” were used to segregate communities without zoning ordinances and to avoid blame being placed on local municipal leaders. They first became popular in 1917 when the U.S. Supreme Court deemed city segregation ordinances illegal.

“When I got to Washington state, I was surprised at how white it was, and now I understand why,” said Thurston County auditor Mary Hall told King5. “So I think it’s time to right the wrong.” Hall found six neighborhoods across Thurston County, including Beachcrest, Stratford Annex 1&2, Lake Sant Clair, Scotts, and Stratford Park, that had racist language preventing non-whites from living in the developments.

The language is both illegal and unenforceable, but Hall explained how it’s been passed down throughout the decades each time someone sells a house.

“When you close on a house you always get a stack of paper and I’m sure most people don’t go through and read all their covenants but it might be interesting to take a look and see if those unlawful, restrictive covenants are there,” she said.

After some residents, including Michelle Fearing, began to notice the language, Thurston County sent out letters to homeowners making them aware of the language, and provided directions on how to remove it.

“It was shocking,” said Fearing. “I’m reading it going, ‘Whoa. Wow. That’s crazy.’” She went through the process and got the language removed within an hour.