The struggle for independence, freedom and self-determination in West Papua continues. A province of Indonesia and former Dutch colony, West Papua has experienced political protest, violence and death this past week. This, as protesters call for independence and rail against anti-Black racial discrimination.

The most recent conflict in West Papua, which has taken place for over a week, began with the mass arrest of 43 Papuan students in Surabaya on the island of Java. The students reportedly destroyed a flag in connection with the August 17 day of Indonesian independence. The students barricaded themselves in a university dormitory to protect themselves from an angry mob, and police called them “monkeys,” “dogs” and “pigs” while throwing tear gas canisters into the building, as Time reported.

Two Indonesian students were arrested for attempting to bring food and water to the students, who according to police, were questioned for the “destruction and disposal” of an Indonesian flag that had been hanging outside a student hostel and was thrown in a sewer. As a result of the incident and in response to the racial taunts against the students, protests spread to the West Papuan capital of Manokwari and throughout the province. Similar demonstrations in support of the West Papuans have also taken place in Jakarta, the capital of Indonesia.

Indonesia deployed over 1,000 troops to West Papua, and the government implemented an internet shutdown in the region. Throughout the province, at least six West Papuans and one soldier were killed in the wake of protests of thousands, with police firing live rounds into crowds of protesters. Although witnesses say they saw police fire at protesters, police deny the reports, according to Al Jazeera.

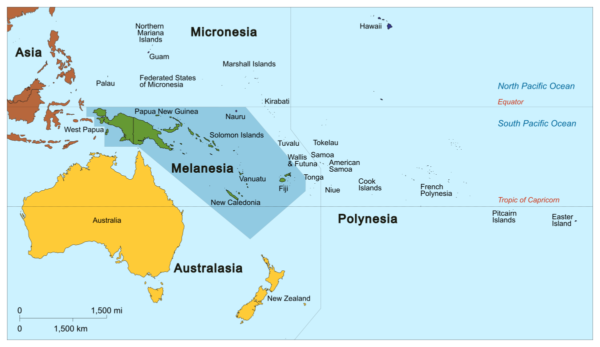

In an interview with CBC News, West Papuan leader Benny Wanda made a renewed call for independence from Indonesia. The people of West Papua are Melanesian, Wanda noted, and as such are different from the people of Indonesia but are the same as the people of Papua New Guinea — which shares an island with West Papua — as well as Vanuatu, Fiji, the French territory of New Caledonia, the Solomon Islands and the Torres Straits in Australia. The ancestors of Melanesians and Australian Aborigines migrated from Africa around 50,000 years ago.

Following the Second World War, there was a question as to whether West Papua, which was then known as Dutch New Guinea and subsequently became Irian Jaya, would become an independent state or a province of Indonesia. In 1961, West Papua declared independence, and the next year Indonesia invaded, occupied the land and killed 30,000 people in the process. Since that time, Indonesia has maintained a brutal military crackdown on West Papua with support from the West.

From the Cold War, the Indonesian military enjoyed equipment and financial support from the U.S., and support for the extermination of 1 million innocent suspected communists and dissidents. The United States also provided lists of Indonesian communist officials to the Indonesian government, and divided up the country’s natural resources after the US-backed purge, encouraging Western corporations to return. According to the Council on Foreign Relations, the U.S.-Indonesian military relationship has encompassed six different programs, including military education and training, anti-terrorism and counter-terrorism training, spare parts, military financing and general economic assistance, which includes funding for police and security forces.

The history of East Timor — the independent former Portuguese colony that Indonesia occupied from 1975 until 1999 — provides a sense of what West Papua faces amid a backdrop of Indonesian military brutality. In 1999, the U.S. pushed for stronger military ties with Indonesia and continued aid to its dictatorship under Suharto, even as the State Department knew Indonesia was supporting armed militias in East Timor and planning to stop the East Timorese independence referendum “through terror and violence.” East Timor won independence, but only after an occupation that resulted in the genocide of somewhere between 100,000 and 200,000 people.

West Papua has been called the “new East Timor” in terms of and the “slow-motion genocide” taking place there and the extent of the police and military repression its people have endured. Kornelius Purba, an editor at the Jakarta Post, believes West Papua could gain independence not unlike East Timor. “Many will no doubt blame the United States or Australia if a Papua exit comes to pass,” Purba wrote. “But seeing the racial abuse against Papuan students and the heightened reactions in Papua, we Indonesians, not just the government, should blame ourselves. We have treated the Papuans the same way we did the people of East Timor.”

Wenda has noted that human rights groups are banned in West Papua, as are human rights groups and international media. “UN denied access to investigate. > Over 500,000 civilians have been murdered > Racism, discrimination, rape & torture are the norm. …and Indonesia wonders why we want freedom!” Wenda tweeted, referring to the genocide of more than 500,000 West Papuans over the past five decades. The exiled leader has called on the UN to intervene, concerned that Indonesia will turn the area into a “bloodbath.” This, as the Southeast Asian nation has resisted calls for independence and has been accused of eliminating West Papuan independence leaders.

For years, Papuans have faced racial discrimination and been treated like second-class citizens. Independence leader Victor Yeimo told the Guardian that West Papuans were angry not “just because they call us monkeys, but because they [Indonesia] treat us like animals.” In 2017, 1.8 million Papuans — over 70 percent of the indigenous population of 2.5 million, and less than 1 percent of Indonesia’s population of 271 million — signed a petition that was delivered to the United Nations Special Committee on Decolonization demanding a vote for West Papuan independence. The petition was subsequently delivered to the UN Human Rights chief in 2019.

With an increase in violence in West Papua, Pacific leaders have been prompted to take a stronger stand. “Something more has got to be done because the human rights situation is worsening,” said Ralph Regenvanu, the foreign minister of Vanuatu, whose Melanesian nation is an ardent supporter of West Papuan independence. “The trauma that they are dealing with which is decades old just keeps compounding because they are marginalised, [and] they struggle for a sense of hope,” said Pacific Council of Churches general secretary Reverend James Bhagwa. “The issue is that people are suffering. We are Pacific people, and in the Pacific when someone is suffering you do something. You don’t let your Pacific brothers and sisters suffer, that’s not the Pacific way,” he added.

The latest protests from West Papuans seeking independence and the resulting bloodshed brought about by the Indonesian military are proof that the issue of racial injustice and oppression against West Papua is receiving heightened attention, and only shows signs of intensifying.