Wreckage from the last known ship to bring enslaved Africans to the United States has been discovered in the murky waters of the northern Gulf Coast near Alabama, historians confirmed Wednesday.

In a statement, the Alabama Historical Commission said remains of the schooner Clotilda were identified and verified near Mobile after several months of assessment.

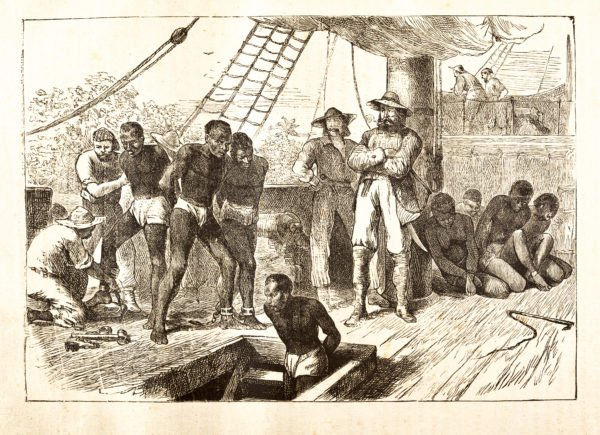

The Clotilda illegally carried 110 people from modern-day Benin in West Africa to Mobile, Alabama, in 1860. (Photo by Grafissimo/Getty Images)

“The discovery of the Clotilda is an extraordinary archaeological find,” said the commission’s executive director Lisa Demetropoulos Jones, adding that the ship’s journey “represented one of the darkest eras of modern history,” and the wreck provides “tangible evidence of slavery.”

The surprising find comes nearly a year after archaeologists thought they’d discovered the lost ship, which was used to illegally transport 110 enslaved Blacks from modern-day Benin to Mobile in 1860, then sailed into the delta and burned to hide the evidence.

The rig was never seen again.

Captives brought over on the Clotilda were eventually freed and settled in a community now known as Africatown USA after their passage back to the Motherland was denied.

Joycelyn Davis, a sixth-generation descendant of one of the Africans brought over on the ship, told The Associated Press she got chills after learning that the wreckage had been discovered.

“I think about the people who came before us who labored and fought and worked so hard,” Davis said. “I’m sure people had given up on finding it. It’s a wow factor.”

Those who arrived aboard the Clotilda are believed to be among the last of an estimated 389,000 Africans delivered into slavery in the mainland U.S. between the early 1600s to 1860, National Geographic reported. Thousands of ships were involved in the trans-Atlantic slave trade, though few wrecks have ever been found.

Fredrik Hiebert, an archaeologist-in-residence for the National Geographic Society, which supported the search for the Clotilda, said the discovery sheds new light “on a lost chapter of American history.”

“This finding is also a critical piece of the story of Africatown, which was built by the resilient descendants of America’s last slave ship,” Hiebert added.

In 2018, Mobile-area journalist Ben Raines stumbled upon the wooden remains of what he initially believed was the Clotilda after abnormally low tides left a portion of the shipwreck exposed. The remains turned out to be that of another vessel, however, and the hunt for the Clotilda raged on.

What’s left of the ship and what researchers plan to do with the remains is still unclear. In addition to evidence of fire, commission officials said the dimensions and construction of the wreck match those of the Clotilda, as do the building materials used for the ship.

“Clotilda was an atypical, custom-built vessel,” explained maritime archaeologist James Delgado. “There was only one Gulf-built schooner 86 feet long with a 23-foot beam and a six-foot, 11-inch hold, and that was Clotilda.”

Though there was no nameplate or other inscribed artifacts to positively ID the ship, Delgado said just “looking at the various pieces of evidence, you can reach a point beyond reasonable doubt [that it’s the Clotilda].”

Officials said they now have plans to to preserve the site where the wreck was located.

The U.S. outlawed the importation of enslaved Blacks in 1808, but that did little to stop smugglers from sailing the Atlantic and filling their ships with captives. Southern plantation owners demanded workers for their cotton fields, but federal regulation wouldn’t allow it.

According to National Geographic, a wealthy landowner and shipmaker named Timothy Meaher allegedly bet several Northern businessmen $1,000 that he could smuggle a cargo of Africans into Mobile Bay without suspicion from federal officials. And he did just that.

The Clotilda arrived in Mobile in 1860 and was quickly scuttled to destroy evidence of the illegal trip to West Africa.

“They were smuggling people as much for defiance as for sport,” historian Natalie Robertson told AP.

Alabama historical commission officials plan to release an official archaeology report on the findings at a community celebration in Africatown on May 30.