Australia, a country taken over by white colonizers after the Black indigenous population had lived there for 65,000 years, will now determine if Aboriginal people without Australian citizenship are aliens who are subject to deportation.

There is a case before the High Court of Australia that will establish whether an indigenous person can be considered an alien under the nation’s constitution. Two men, Daniel Love and Brendan Thoms, have filed a lawsuit in which the court will determine whether an Aboriginal Australian with at least one Australian parent — one who was born in another country, came to Australia as a young child and has only left the country briefly — and is not an Australian citizen is an alien under section 51 (xix) of the Australian Constitution. That section allows the Parliament to enact laws concerning “naturalization and aliens.”

The answer the plaintiffs have gotten is no. “For descendants of Australia’s first peoples, an indelible part of the Australian community, to be ‘aliens’ for the purposes of Australia’s Constitution, is antithetical to their indigeneity and to the social, democratic and political values which underpin and are protected by the Constitution The concept of Aboriginality is inconsistent with the concept of alienage,” the men say in their filing with the court.

Under a 2014 federal immigration law, known as a “bad character” law, deportation is mandated for people living in Australia with visas who are sentenced to at least 12 months of imprisonment. The Australian government wants to make their immigration laws even more draconian by broadening the government’s power to revoke visas of people with criminal records. The policy has increased the deportation of people who have lived in Australia most of their lives to countries such as New Zealand, Papua New Guinea or other islands in the Pacific, even when those people have no ties to the country to which they are returned. One third of the 1,300 people in immigration detention are there based on bad character, and in New Zealand, where the Australian deportation plan has been criticized, 600 people were returned in 2017.

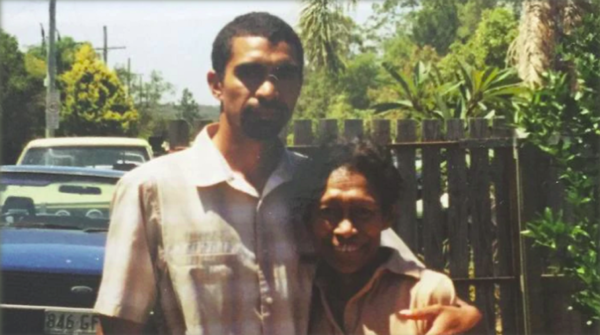

Daniel Love, 39, is a member of the Kamilaroi people who was born in Papua New Guinea to an Aboriginal Australian father and a Papua New Guinean mother. Love is also a common law holder of native title —traditional land rights claimed by Aboriginal Australian people under the original ownership of the land. He has been a permanent resident of Australia since the age of 6, but his parents did not complete the necessary paperwork to obtain his Australian citizenship. Last year, Love was sentenced to 12 months in prison on an assault charge. The government canceled his visa and Love was placed in immigration detention. After spending seven weeks in detention, Love was released and the government revoked the cancellation of his visa.

Love sued the government for AU$200,000 (US$142,920) in compensation for false imprisonment, claiming the government illegally detained him and that he has suffered loss of appetite, sleep deprivation and anxiety. He was unable to see his five children, all of whom are Australian citizens, and feared for his safety with the prospect of being sent to a country with which he has no family connections.

Similarly, Brendan Thoms, 31, is a Gunggari man born in New Zealand to an Aboriginal Australian mother and a New Zealander father. Thoms was entitled to Australian citizenship by birth but has not acquired it, and has lived in Australia since the age of 6. He was sentenced to imprisonment of 18 months for assault causing bodily harm, and his visa was canceled because he was deemed an “unlawful non-citizen.” Thoms, who has one Australian child, remains in detention.

In its own court filings, the Commonwealth of Australia claims that whether Love or Thoms is an Aboriginal person or is a common law holder of native title is irrelevant in determining if they are aliens. Rather, the government argues that what is important is the men are not citizens and they owe allegiance to a foreign country, and that having an Australian parent or deep ties to the country is irrelevant. “Accordingly, as persons who are not Australian citizens, the Plaintiffs are, and always have been, aliens,” the government argues, adding “it was recognised that the effect of Australia’s emergence as a fully independent sovereign nation with its own distinct citizenship … that the word ‘alien’ in s 5 l(xix) of the Constitution had become synonymous with ‘non-citizen’.”

The state also claims that “Aboriginality does not prevent a person from being an alien,” particularly when that person is a citizen of a foreign country. The citizens of Papua New Guinea, the commonwealth claims, may have traditional and cultural associations with the Torres Strait Islands of Australia — which lie between Papua New Guinea and Australia — yet they are still regarded as aliens.

This case comes in a country that granted citizenship to indigenous people only relatively recently, with a 1967 referendum to include Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in the national census for the first time. Prior to that time, Black people were rendered invisible and treated like animals, supposedly “discovered” by the British in 1788, although they had lived on the land for millennia. Now there is cruel irony in the fact that indigenous Black people would be regarded as aliens on land stolen from them.