CHICAGO (AP) — A federal judge on Thursday approved a far-reaching plan for court-supervised reforms of the Chicago Police Department, nearly two years after a U.S. Justice Department report found a history of civil rights violations by officers.

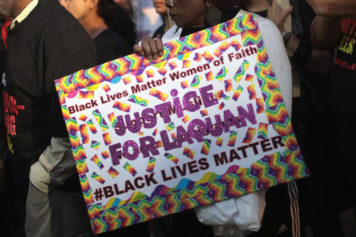

Judge Robert Dow’s decision to approve the consent decree is a culmination of a process that started with the release of video in 2015 showing white police officer Jason Van Dyke shooting black teenager Laquan McDonald 16 times. It led to the Justice Department investigation.

FILE – In this Jan. 18, 2019 file photo, former Chicago police Officer Jason Van Dyke attends his sentencing hearing at the Leighton Criminal Court Building in Chicago, for the 2014 shooting of Laquan McDonald. (Antonio Perez/Chicago Tribune via AP, Pool, File)

Dow says the decree is a “vehicle for solving … common problems … in a manner that defuses tension, respects differences of opinion.”

Former Illinois Attorney General Lisa Madigan and Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel unveiled the 200-plus page decree in July. It addresses everything from police recruitment to using force.

Among the reforms contained in the July draft are requirements that officers issue verbal warnings before any use of force and provide life-saving aid after force is used. It also set a 180-day deadline for investigations to be completed by the police department’s internal affairs bureau and the Civilian Office of Police Accountability, and calls for better training and supervision of officers.

Dow could have altered some provisions, though it wasn’t immediately clear if he had done so.

A key to the plan is an independent monitor appointed by the judge. The person would ensure that hundreds of changes called for in how police work actually happen and report to the judge on whether the city is hitting reform benchmarks. The oversight would continue until a judge determines the city has fully complied, a process that is likely to take at least several years.

The plan would build on some changes the department already has made, such as issuing body cameras to every officer.

Madigan, with Emanuel’s support, sued the city last year to ensure court oversight was a central feature of any reform plan. The lawsuit killed a draft plan negotiated with President Donald Trump’s administration that didn’t envision a court role in reforming the department — a departure from practice during President Barack Obama’s administration of using courts to change troubled departments.

Chicago’s police union has sharply criticized the legal action, saying a consent decree would make it harder for officers to do their jobs and put officers’ lives in danger. Former U.S. Attorney General Jeff Sessions criticized has consent decrees, saying they can unfairly malign good officers.

The damning Justice Department report released in the waning days of the Obama administration in January 2017 found that deep-rooted civil rights abuses permeate Chicago’s 12,000-member force, including racial bias, a tendency to use excessive force and a “pervasive cover-up culture.”

Madigan acknowledged in July that there had been many attempts over decades to reform the department and the relationship between police and the community. But she expressed confidence this time would be different. Emanuel said in July at that plan would “stand the test of time.” He called it “enforceable, sustainable and durable.”