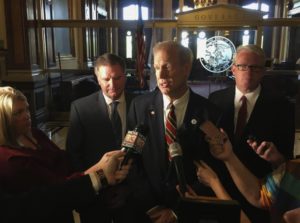

Gov. Bruce Rauner, center, addresses reporters outside his state Capitol office in Springfield, Ill. Rauner, a Republican, wants to reinstate the death penalty in the state. (AP Photo by John O’Connor File)

SPRINGFIELD, Ill. (AP) — Eight years after Illinois abolished the death penalty, the state’s Republican governor on Monday proposed reinstating the punishment for mass killers and people who gun down police officers.

Gov. Bruce Rauner tied the death penalty plan to gun restrictions favored by Democrats who control the Legislature — inserting it into legislation that lengthens the waiting period for taking possession of rifles or shotguns from 24 hours to 72 hours, and adding other limits on firearms possession.

“I don’t believe that this is anything other than very good policy, widely supported by the people of Illinois,” Rauner said of the death penalty proposal while at the Illinois State Police forensic laboratory in Chicago. “These individuals who commit mass murder, individuals who choose to murder a law enforcement officer, they deserve to have their life taken.”

The last execution to be carried out in Illinois was in 1999, before Republican Gov. George Ryan issued a moratorium and later emptied death row, believing the system too fraught with mistakes to be tenable. Illinois had executed 12 people in the decades since the U.S. Supreme Court reinstated capital punishment in 1976, but 13 people had been freed because of questions about their guilt. Democratic Gov. Pat Quinn officially abolished the death penalty in 2011.

Rauner, an unpopular first-term governor facing a tough road to re-election in November, used his amendatory veto authority to add capital punishment and other provisions to the gun bill, including a ban on bump stocks, the rifle-firing speed accessory used in a mass shooting in Las Vegas last year. He also proposed giving the courts the authority to take guns from people deemed dangerous.

Democrats pushed back. Senate President John Cullerton of Chicago said in a statement that “the death penalty should never be used as a political tool to advance one’s agenda.”

“Doing so is in large part why we had so many problems and overturned convictions,” Cullerton said.

Democrats have introduced several proposals to curb gun violence — in response not only to mass shootings elsewhere in the U.S. but also because of the Feb. 13 fatal shooting in downtown Chicago of police Commander Paul Bauer.

The bill now goes back to the House. For Rauner’s plan to become law, the Legislature must approve his changes. If lawmakers do not act, the whole package will expire without becoming law. The Legislature could also vote to override Rauner’s changes and enact the original waiting-period language.

Steve Brown, spokesman for House Democrats, said the first task will be to determine whether Rauner exceeded his authority. The Illinois Constitution says the governor may send a bill back “with specific recommendations for change,” and Democratic House Speaker Michael Madigan has repeatedly taken a narrow view of that power.

Rep. Jonathan Carroll, a Northbrook Democrat and House sponsor of the original measure, would not comment Monday, saying he needed time to examine Rauner’s action.

Rauner’s proposal would allow a jury to impose the death penalty only in cases where someone is found guilty “beyond all doubt” — a higher standard than the constitutionally guaranteed “reasonable doubt” requirement for most criminal cases. He told reporters that would eliminate cause for concern, noting that “so many times, the person is caught in the act” or “there are multiple witnesses, and they’re fleeing the act.”

But Robert Dunham, executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center in Washington, D.C., said Illinois is rife with examples of recanted eyewitness testimony and confessions beaten out of suspects by police. Dunham, whose organization is officially neutral on the death penalty but often criticizes its application, said a “beyond all doubt” standard would still be open to interpretation.

“Illinois’ death penalty history showed how arbitrary and unreliable the death sentence was and how susceptible it was to official misconduct,” Dunham said. “Any suggestion that it should be brought back without a full public discussion and full public hearings is incredibly reckless.”