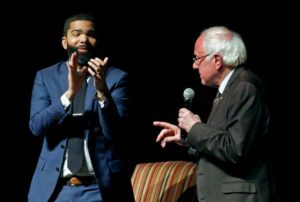

In this April 4, 2018 photo, Jackson Mayor Chokwe Antar Lumumba, left, applauds as U.S. Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., answers a question during a town hall meeting examining economic justice 50 years after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., in Jackson, Miss. (AP Photo/Rogelio V. Solis)

JACKSON, Mississippi (AP) — Bernie Sanders took the stage in Mississippi’s capital city alongside a popular, young African-American mayor whose election he’d endorsed last year.

Sanders, the one-time and potentially future presidential candidate, praised Jackson’s Chokwe Antar Lumumba as an heir to the legacy of Martin Luther King, not just on civil rights for black Americans but economic justice for poor and working-class Americans. Yet on the same night, Lumumba and Sanders gathered to honor the slain civil rights leader, the Vermont senator seemed to downplay another iconic black American.

Former President Barack Obama, Sanders said, was a “charismatic individual … an extraordinary candidate, a brilliant man.” But “behind that reality,” Sanders continued, the nation’s first black president led a Democratic Party whose “business model” has been a “failure” for more than a decade.

It served as the latest confirmation that Sanders, even as he tries for new footholds in the black community, hasn’t mastered his precarious relationship with a key Democratic Party constituency that effectively blocked his White House path in 2016 with its overwhelming support for Hillary Clinton; it’s a constituency he will need if he hopes to reshape the party going forward, much less make another presidential run.

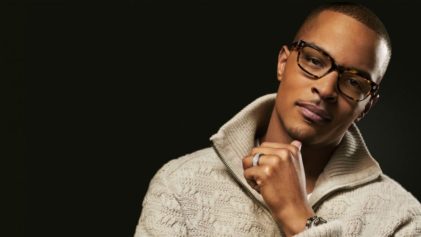

Sanders, who is elected in Vermont as an independent but caucuses in Washington with Democrats, has been spending more time in places dominated by black voters, including Southern states where African-Americans shape Democratic primaries. He and Lumumba have become a sort of political odd couple: the white 76-year-old democratic socialist with his rumpled suit and untamed hair, preaching in his Brooklyn accent, and an impeccably clad 35-year-old black attorney-turned-politician smiling his way through calm expositions sprinkled with the occasional “y’all.”

But they share a common vision. Lumumba expresses hopes to make Jackson “the most radical” of U.S. cities.

Besides campaigning for Lumumba, Sanders came to Mississippi last year to lobby workers to unionize a Nissan auto plant.

The senator backed another black millennial in neighboring Alabama, helping Randall Woodfin to the mayor’s office in Birmingham. In New Orleans, Our Revolution, the spinoff of Sanders’ presidential campaign, tapped the eventual winner of a crowded mayoral race. LaToya Cantrell will be sworn in May 7.

On Capitol Hill, Sanders aides say he huddles more routinely with black lawmakers to discuss shared priorities.

In an interview in Mississippi, Sanders brushed back “the myth” that he has little black support, noting 2016 primary exit polls showing he won voters under 30 across racial lines. But he mostly shuns most race-based analysis and casts his post-2016 manoeuvring as ideological: He wants to move public policy leftward on everything from health care and college access to criminal justice and labor policy, and he argues the way to do that is increase voter turnout across demographic groups.

“My goal is to bring forth a progressive agenda that speaks to the needs of working people, whether they are black, white or Latino, and get people involved in the political process in a way we have not seen in a very long time,” he said in an interview before his event with Lumumba.

His mentions of the civil rights movement still don’t include his own activism as a white college student in Chicago.

His travel itinerary has been void of state and local party galas where lower-level party players are accustomed to welcoming would-be presidents. Clinton attended such events for decades, and by her presidential campaigns often could call several attendees by name.

“We haven’t heard from him at all,” said Alabama’s Joe Reed, who leads an influential black caucus within his state’s party.

Georgia’s Nikema Williams, her state party’s vice chairwoman and a first-term state senator, said the same. Sanders came to Atlanta last year to campaign for a black mayoral candidate who ultimately lost, but didn’t reach beyond Vincent Fort’s campaign circle.

As a comparison, Williams said Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren, a possible 2020 candidate, called to congratulate her after her election. “It struck me that she’d be calling a new state senator in Georgia,” Williams said.

Sanders answered that he doesn’t need “the establishment,” regardless of race, and said most voters are “estranged” from the two-party system anyway.

As with Sanders’ comments on Obama, some of the rub is as much about emphasis as substance. Seated with Lumumba, the senator was asked about the marginalization of black LGBTQ citizens. He shifted the question to people “you didn’t talk about” like “people working two or three jobs” and “people who spend 50 percent of their limited income on housing.” He repeatedly turned the discussion of fighting racism to fighting poverty.

“If all I hear about is ‘the working class,’ and it seems he’s talking to just one segment, then it’s easy to feel he’s not talking to me,” said Williams, the Georgia Democrat.

Exit polling from the 2008 and 2016 Democratic presidential primaries showed that the eventual nominee — Obama, then Clinton — actually lost the cumulative white vote, but prevailed on the strength of non-whites, particularly black voters.

Those trends may not apply neatly in 2020, when the Democratic field is expected to include well more than two competitive candidates. There could be multiple credible black candidates, including Sens. Kamala Harris of California and Cory Booker of New Jersey.

But Clay Middleton, who ran Clinton’s South Carolina campaign in 2016, said the takeaway remains: “You want to get elected president, you want to win the nomination, you cannot take the African-American vote for granted.”

Reed, the Alabama Democrat, offered a warning both to Sanders and black Democrats.

Black voters, Reed said, must recognize that “we can’t elect a president by ourselves” and that any victorious candidate must “appeal to more than just us.” But any presidential hopeful, Reed said, must understand that black voters “will look for somebody that looks out for our interests.”