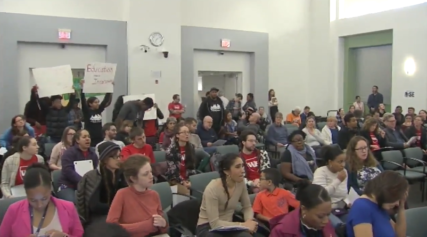

Philadelphia’ supervised injection facilities or “CUES” will offer additional resources such as rehab and social services. (Photo by Spencer Platt/Getty Images)

Philadelphia city officials announced this week its plans to become the first municipality in the nation to open a supervised injection facility, or SIF, allowing intravenous drug users to shoot up safely under the supervision of trained medical professionals.

The announcement comes just two weeks after Pennsylvania Governor Tom Wolf declared the city’s overdose crisis a public health emergency, according to In Justice Today. During an afternoon news conference on Jan. 30, Mayor Jim Kenney laid out his administration’s rationale behind the controversial decision.

Their goal? To save more lives and help communities affected by public drug use through a concept called “harm reduction.”

“These are unprecedented times and we are taking unprecedented steps,” Philly Managing Director Michael DiBerardinis said, adding that the city will encourage the private sector to launch “one or more Comprehensive User Engagement Sites,” or CUES . The city settled on this term over “SIF” to reflect its additional efforts of offering clients resources to recovery, such as rehab and social services, the newspaper reported.

“We don’t see these sites as solely for supervised injection,” DiBerardinis’ first deputy, Brian Abernathy, noted. “They will serve as pathways to get people into treatment.”

Several cities and states across the nation have been in talks to open similar facilities offering supervised drug use, including New York, Seattle and even Atlanta. However, policymakers’ fight to create “safe spaces” for drug users shines a glaring light on the double standard of the steps willing to be taken when the users aren’t largely Black.

California Sen. Kamala Harris (D) addressed such racialized standards at a conference last summer, pointing out the differences in how we discuss the crack epidemic of the ’80s and early ’90s and the troubling opioid crises of today. Using a series of news headlines, Harris illustrated the stark differences in how predominately Black crack users were characterized using dark, demeaning language compared to white opioid users,, who are often described with more compassion.

Not to mention, Black drug users were criminalized and thrown in jail at astounding numbers for their addiction — not offered a free clinic to shoot up in.

“Folks, let me tell you: These crises have so much more in common than what separates them,” she told conference-goers. “… As you can see, this is not a Black and brown issue This is not an urban and blue-state issue. It has always been an American issue.”

In the case of Philadelphia, the city will tackle its public drug use issue by giving private organizations/groups the go-ahead to create supervised injection facilitates. This way, a dedicated team of advocates could raise their own money and set up shop without the bureaucratic red tape commonly associated with city funding approval, according to In Justice Today.

A recent study commissioned by Mayor Kenney’s administration found that such CUES or “SIFs” could save the city nearly $100 million per year in healthcare costs and fatalities. Naturally, the plan still has its critics, however.

“Philadelphia’s fatal overdose rate is the worst in the nation among large cities, and incidents of overdose have steadily increased to an alarming degree,” Kenney said. “I applaud the work of the Task Force and city leadership in taking this bold action to help save lives.”