Who deserves credit for the record low Black unemployment rate?

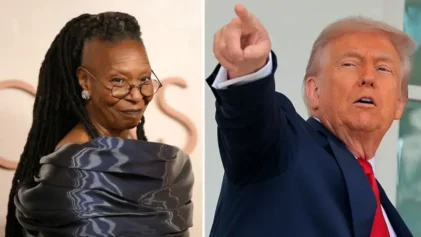

A week after January 1, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that the national unemployment rate had remained largely unchanged at 4.1 percent. It further revealed the unemployment rate for Black Americans had fallen to 6.8 percent, the lowest recorded level since the 1970s. The latter would prompt President Donald Trump to assume credit in a less-than-surprising, self-congratulatory tweet. “African American unemployment is the lowest ever recorded in our country,” boasted Trump, noting the “Dems did nothing for you but get your vote!”

Twitter trolling aside, what do such numbers really represent for African-Americans? And how did we arrive at the current record figure of 6.8 percent?

“It shows that the expansion in the economy that started during the Obama administration is still going on,” said Dr. Steven C. Pitts, associate chair of the Center for Labor Research and Education at University of California, Berkeley. “We can still question the quality of jobs, but in terms of the number of people who have jobs and who are looking for work, we see a steady decline in the unemployment rate.”

“As one metric of how the economy is doing, that one metric says the economy is doing well,” continued Pitts. He described how the Bureau of Labor Statistics will identify roughly 60,000 households to survey, noting one question they ask is, during a certain week of the month, “Were you employed?” Pitts pointed out there are other ways to measure economic performance including job security, wages and benefits. But, he added, “if we take a narrow perspective, and we just focus on unemployment, then it’s the lowest it has been in a long, long time.”

Some take a more comparative perspective. “Black unemployment, while it may be down, is still almost double that of white unemployment,” said James E. Clingman, a longtime economist, professor, writer and activist for Black economic empowerment. Regarding this disparity, Clingman pointed out that “if you look all the way back to the 1960s you’ll see the same thing.” While politicians are playing up the fact that it’s dropping, “you have to consider what kinds of jobs are available to Black people,” stressed Clingman, echoing Pitts’ reference to quality. “A lot of the jobs that have contributed to the low unemployment, of course, are service jobs which don’t pay a lot, that’s why we see stagnant wages. So while we can brag about the percentage going down, you have to look beneath that to see just how much wages have increased, which is relatively small, if at all.”

A deeper look, for some, is not on the agenda. “The lowest in nearly 5 decades and a credit to @POTUS economic policies!!” tweeted Trump press aide Raj Shah, crediting the news to the economic policies of Trump’s first year in office.

Pitts is more focused on the economics of the data than on the politics of who deserves the recognition.

“To be honest, I’m not trying to give credit one way or the other since we have a tendency to always give credit to presidents in good times, and give blame during bad times,” offered Pitts, Still, he clarified the lower employment trend is “not a new trajectory” that somehow began in November 2016, but a “continuation of the expansion that’s been happening since the Obama administration.”

Yet even with the positive trend and record low figure, at almost 7 percent, Black Americans are still struggling with and suffering from serious levels of unemployment, especially in comparison to their white counterparts. “6.8 percent unemployment rate for African Americans is lowest on record,” tweeted economist Dean Baker of the Center for Economic and Policy Research. “Good news, except pretty bad news that this is the best ever.” An ongoing educational gap may contribute to this employment disparity of almost three percentage points between African-Americans and whites, given only 23 percent of African-American adults have at least a bachelor’s degree as compared with 36 percent of whites.

However, several economists at the Federal Reserve have downplayed this connection after finding this education disparity does not account for the substantial difference in employment. Upon conducting research revealing nominal educational attainment to be an ineffective gauge of market skills and employability, these federal economists concluded that incarceration and discrimination were likely significant contributors to such employment disparities. “Yet another factor that is likely to play a role, at least for black-white male gaps, is incarceration,” the federal study read. “As is well-known, incarceration rates in the United States are much higher than in other advanced economies, and are particularly elevated among black men.” Not surprisingly, it further noted, “Research has shown that incarceration reduces the future labor force participation and employment prospects of the affected population” given the difficulty many have at securing employment upon release.

Still, discrimination may have the greatest impact on disparities in employment. A 2004 field experiment on labor market discrimination by noted economic professors Marianne Bertrand and Sendhil Mullainathan had them respond to job ads in newspapers in Boston and Chicago with fake identical résumés. The only difference were the names they used as half the resumes were headed by names common to whites, and the others with common African-American names. Despite the résumés being otherwise identical in every detail, the white candidates received 50 percent more job interviews. The economists concluded, “Differential treatment by race appears to still be prominent in the U.S. labor market.”

Consistently, even with the recent record-level figures for Black unemployment nationally, some feel they don’t effectively portray the plight of Black workers at the state or local levels.

“I think the actual numbers are higher,” said Priscilla Flint-Banks, vice president and co-founder of the Black Economic Justice Institute in Massachusetts. While the racial unemployment disparity in Massachusetts has tended to mirror or be greater than the national disparity, Flint-Banks has little faith in politicized numbers and is more concerned by her local reality. “I know that, here in Boston, our unemployment is horrible,” she stressed, noting that “people of color, and Black people in particular, are just not getting these jobs.” She goes on to depict how African-Americans in Boston are fighting to gain access to good-paying construction jobs and simultaneously advocating for a higher minimum wage given the gentrification and increasing rents pushing them out of city neighborhoods. “I believe we should really look at starting our own businesses like Black markets and Ujamaa markets and places where we can buy from and employ each other,” added Flint-Banks.

Regardless of the politics behind the national employment rate or who should ultimately get credit for it, Clingman, like Flint-Banks, is more focused on the road ahead and how the Black community can best economically navigate it.

“I think we have to look deeper than just a stat,” insisted Clingman. “We Black people — Black businesses and consumers — must adopt strategies to employ our own people.” To do this, “we have to start and grow businesses to the point where we can hire our own and, if you look deeply enough, you have to come to that conclusion. Because if we’re not providing jobs for our own young people, you know that nobody else is going to do it to the point that’s going to pull us up.

“They want us to be consumers of everything that they make,” continued Clingman. “So we need to move from that side of the economic equation to the employment and production side to improve our numbers ourselves.”