When it comes to the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), it’s hard to imagine things could get any worse. Over the past two decades, an estimated 6 million people have perished in the DRC due to war, foreign invasion, internal conflict, regional violence and international exploitation. Nonetheless, the United Nations’ recent activation of its highest level of emergency, Level 3 (L3), reveals just how dire a crisis still exists in the resource-rich nation that sits at the heart of the African continent. The L3 designation, which mobilizes additional funding and resources to meet emergency needs, puts the DRC in the same crisis category as such international emergencies as Iraq, Syria and Yemen.

Sadly, the worst may be far from over. “As many as 250,000 children could starve in Kasai in the next few months unless enough nutritious food reaches them quickly,” said David Beasley, executive director of the World Food Program, returning from a four-day mission to Kasai. “We need access to those children, and we need money — urgently.”

While political violence had mostly been relegated to the eastern Great Lakes region where natural resources are abundant, it recently intensified in Kasai as a result of president Joseph Kabila’s repression of unrest stemming from his rejection of his constitutionally-mandated two-term limit, which ended in December 2016. The government has yet to authorize new elections as the president has claimed both a lack of national preparation and a priority for putting down rebel groups in the East. In a recent and rare interview with SPIEGEL magazine, the embattled Kabila offered, “We are not going to finance elections when we need to fight to win back occupied territory.”

Despite mounting international pressure — recently represented by the October Congo visit of U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations Nikki Haley — the Kabila regime has continued to stall the elections process as government security forces, state-backed militias and local armed groups have killed an estimated 5000 people in Kasai since August 2016, with 600 schools attacked, 1.4 million people displaced, and 90 mass graves. In March, two United Nations investigators, one American, one Swedish, were executed while examining human rights violations in Kasai, and their four Congolese escorts went missing. A subsequent Human Rights Watch and Radio France Internationale investigation suggested government responsibility for the murders.

Given the United States’ longtime support of the violently repressive and undemocratic Kabila — and given Kabila has not adhered to previous diplomatic agreements or even massive monetary payments to get him to step down — some have little faith in American pressure.

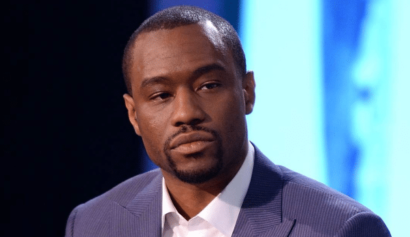

“You can understand why the Congolese people basically feel like the U.S. is playing with us and that they’re not serious,” said Maurice Carney, co-founder and executive director of the Friends of the Congo. A longtime advocate for the DRC, Carney started the Washington DC-based nonprofit in 2004. “They sent one ambassador in 2016, they sent another in 2017, and all we know is that Kabila is still in power, elections are not organized, and we don’t have the opportunity to choose our own leaders.” In the meantime, noted Carney, “The country, for all intensive purposes, is on fire.”

The crisis in Kasai is the latest in a nation consumed by suffering. To the east, in the DRC’s mineral-rich Kivu region where armed groups both foreign and local war for gold, coltan, tin, copper and tungsten, civilian massacres, widespread rape, and the forced recruitment of child soldiers continues with impunity. And, just this week, the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights was informed a cholera epidemic has spread across the country as famine is expected to affect 7.7 million people.

Still, Carney clarifies what’s ultimately behind such immense suffering and inhumanity. “At its root, the crisis is not a humanitarian one, it’s a political one.” Consistent with the murderous politics that have historically provoked humanitarian nightmares in the country, Carney noted how many children in the formerly peaceful Kasai are facing starvation after government security forces killed an aspiring local chief and his family who were opposed to Kabila. “What that did was spur a response from the followers of the chief, and the Congolese government responded, in turn, in a heavy-handed way,” explained Carney, noting how this facilitated the violence and displacement that has plagued Kasai since August 2016.

Such heavy-handed violence plagued the Congo even before it was a country. From 1885 to its 1908 colonization by Belgium, King Leopold II brutally dominated the region as his own private property, slaughtering an estimated 10 to 15 million natives during his extraction of the region’s excessive natural wealth. With its independence from European colonialism a half-century later in 1960, the Congo was thwarted by violence again as international and local interests conspired to subsequently remove from office and assassinate its first democratically elected prime minister, Patrice Lumumba.

Upon the Rwandan genocide of 1994 — when as many as one million Tutsis were wiped out over 100 days in a mass slaughter led by the Hutu majority against their ethnic minority neighbors — hundreds of thousands of Hutus fled Rwanda and an advancing Tutsi-led fighting force to seek shelter in refugee camps in the eastern part of what was then known as Zaire. The Tutsi forces pursued the Hutus across the border, resulting in more killing and regional instability. In 1997, with the backing of Rwanda and Uganda, rebel leader Laurent Desire Kabila wrested power away from longtime dictator Mobutu Sese Sekou and reverted the country’s name to the Democratic Republic of the Congo. A year later, Rwanda attempted to remove Kabila from office, triggering a regional war involving nine African nations, including the DRC, Rwanda and Uganda.

In January 2001, Kabila was assassinated and his son, the current president, assumed power. Although the war was officially declared over in 2003, the prized eastern or Kivu region of the country has remained unstable as Congolese natives are massacred, raped and exploited at the hands of violent local and internationally-backed factions bent on profiting from its wealth of natural resources. And while the United Nations has had a peacekeeping presence in the DRC for almost two decades, its role in curbing the conflict has ranged from ineffective to complicit in an ongoing and tragic saga heavily influenced by Western interests.

“President Kabila, who has caused this crisis in the Congo today, is a product of the United States,” said Congolese activist and journalist, Kambale Musavuli, in a December 2016 interview upon the violent crackdown on those protesting delayed elections in Kasai and elsewhere. Musavuli noted that the United States was one of the first nations to support and legitimize the presidency of Kabila in the highly-questionable Congolese elections of 2006 and 2011. Despite widespread fraud and intimidation, American taxes are still funding militarized police and government-backed repression in the DRC, as they have for five decades.

Carney points to the exponential expansion of the military footprint on the African continent through AFRICOM over the past decade as being enacted “ostensibly to protect U.S. strategic interests” like oil and minerals vital to US aerospace, military, technology and communications industries including “Congo’s copper, cobalt and coltan or, in the case of Niger, uranium.”

“So you have the U.S. supporting regimes like Paul Kagame’s in Rwanda by providing them military equipment, intelligence and financial support with the understanding they are going to be in alignment with U.S. interests on the African continent,” said Carney, noting that “when they commit mass crimes, kill people and violate human rights, the U.S. runs interference on the international level to provide them political and diplomatic cover.”

The U.S has consistently supported proxy regimes in Rwanda and Uganda that have further destabilized the DRC and facilitated the ongoing extraction of the country’s natural resources. A 2010 United Nations Mapping Report criticized the American government for its “very friendly attitude” towards Rwanda and for “overlooking human rights concerns.”

Carney also takes issue with the Western “conflict minerals” approach, the popular international campaign to identify minerals obtained illicitly and by way of conflict and ostensibly aimed at curbing the ongoing resource war in the DRC.

“Talking about conflict minerals really doesn’t get to the heart of the matter,” said Carney. “We need to be talking about resource sovereignty—Congolese having ownership and control over the minerals.” And not just Congolese, he stressed, but Africans, because “this is a challenge throughout the continent. We really need to get the world’s attention on the extent to which the Congo is being plundered and looted, and how we can mobilize the global community to confront these multinational corporations and local elites to get to a point where Congolese, and Africans overall, are controlling the enormous wealth they have in their countries.”

“We know Congo is arguably the richest country on the planet with an estimated 24 trillion dollars in natural resources, and we know Africa is the richest continent, yet has the poorest people,” continued Carney, noting “they’re being looted, pilfered and plundered. So that is what we need to confront.”

Carney outlines numerous methods of doing so, including the need for Americans and others in the international realm to educate themselves on the full context of the ongoing crises in Kasai, the Kivu provinces, and the DRC as a whole, and to demand where their public dollars should not go. “U.S. foreign policy on the African continent has been for access to resources and, specifically for the Congo, its also the case,” offered Musavuli, in the December 2016 interview. “And this is why we appeal to US citizens to put pressure on the government.”

Yet, ultimately, Carney believes the key to ending the bloodshed lies within the heart of the Congo itself. “The Congolese youth are leading the way, and they are educating, informing, mobilizing and organizing, as they represent the majority of the population,” he reported, noting “the median age in the Congo is around 17. And they are rallying to not only confront their local elites but also to confront the international backing that these elites benefit from.”