Anquan Boldin, who won a Super Bowl ring with the Baltimore Ravens in 2013, abruptly retired this summer after signing with the Buffalo Bills. Boldin’s cousin Corey Jones was killed in 2015 by a plainclothes cop who later was charged for the slaying.

All-Pro NFL wide receiver Anquan Boldin inked a new contract with the Buffalo Bills this summer worth nearly $3 million for one season. Weeks later, Boldin pulled a Dave Chappelle. Like the funnyman who walked away from a multi-million dollar television deal, Boldin decided there were things in life more deserving of his time and energy besides football.

Speaking with Sports Illustrated, Boldin cited the Charlottesville, Va., melee, where one woman was killed during a counterprotest against supporters of Confederate monuments, as the tipping point. “I just remember lying in the dorm room and thinking, there’s no way I can continue to play football,” said the gridiron legend.

The recent focus on athletes-turned-activists has centered squarely Boldin’s former teammate Colin Kaepernick, whom many believe is being denied the chance to play football in retaliation for his season-long protest of the national anthem. While Kaepernick was allegedly stiff-armed out of the league, a growing number of Black athletes are voluntarily exiting professional sports because of the anti-Blackness that saturates the sports industry and out of concern for their personal health and safety. Many of these jocks are investing their newfound free time in projects to combat racism and the problems plaguing Black people.

Former running back Rashard Mendenhall ditched his cleats and the NFL years before Kaepernick’s kneeling. At age 26, Mendenhall chose to retire at the peak of his athletic ability and during his most lucrative earning years as a professional player. Feeling compelled to explain why he prematurely ended a successful career, which included two Super Bowl appearances, the former ball carrier provided a heap of specifics in his 2014 farewell essay.

He relished the people, experiences and millions of dollars football allowed him to have, but confessed that in addition to 300-pound tacklers, he had to “fight through waves and currents of praise and criticism, but mostly hate.” Speaking with a retiree’s frankness, Mendenhall added he’s lost count of “how many times [he’s] been called a ‘dumb [n-word]’.”

In addition to racist epithets, Mendenhall eloquently explains how Black athletes are perceived in the same niggling ways as Black people who’ve never scored a touchdown. “I am not an entertainer. I never have been. Playing that role was never easy for me. The box deemed for professional athletes is a very small box. My wings spread a lot further than the acceptable athletic stereotypes,” he wrote.

One of the ways racism injures Black people is by suffocating aspirations. Mendenhall and generations of Black people are propagandized to think physical aptitude is their lone path to brilliance. The extra brawn, puny brain accusation was zealously endorsed for years, and helps explain why white men still most often coach Black athletes at all levels.

Former Baltimore Raven John Urschel grappled on the hyper-violent offensive line by day and moonlighted as a Ph.D, student at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology during his final NFL season. He retired in July, also at the age of 26. Working towards a doctorate in mathematics, Urschel acknowledged his decision to subtract pro football from his life was influenced in part by new research suggesting football players frequently suffer long-term traumatic brain injury. The former Raven sustained a concussion in 2015. Urschel disclosed the damage was so severe he was temporarily unable to solve high-level math problems. For some, it’s incomprehensible that some Black people are now voluntarily leaving the cheerleaders, the field and mountains of cash to preserve their physical well-being.

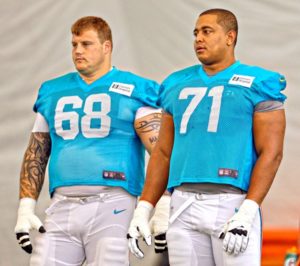

Former Miami Dolphins Richie Incognito (68) and Jonathan Martin (71) had a contentious relationship, with Incognito heaping racist abuse on his teammate. (AP Photo/Lynne Sladky)

Apparently, a daily recurrence of racial abuse is prompting more players to permanently drop the ball. Jonathan Martin played three NFL seasons before retiring at the age of 25. While playing for the Miami Dolphins in 2013, Martin alleged that he was subjected to constant harassment and racist insults from fellow teammates. He also charged that this abuse was tolerated and encouraged by the coaching staff. A lengthy investigation found that Richie Incognito, one of Martin’s white teammates, called him the n-word, mulatto, and “darkness.” Incognito’s brand of humor also included threatening to kill Martin and swapping text messages with teammates about shooting Black people.

If Anquan Boldin had played this season, he would have been Incognito’s new Buffalo teammate. While Incognito remains an NFL employee, Martin wrote publicly about being “petrified of going to work” as a professional football player. The turmoil lead him to substance abuse and multiple suicide attempts. In his time away from the game, he’s nourished his mental health and delivered numerous talks to youth about depression and the importance of practicing self-confidence.

While Martin uses his retirement to encourage children, Boldin now has more time to lobby Congress. Months before his retirement, he shared his personal commitment to end police violence against Black people at a congressional forum on criminal justice reform. Boldin’s cousin, Corey Jones, was shot and killed by a Florida plainclothes officer in 2015. The killing motivated Boldin to conclude: “At this time, I feel drawn to make the larger fight for human rights a priority. My life’s purpose is bigger than football.”

Lifetime activist and Hall of Fame football titan Jim Brown, despite his recent comments about Colin Kaepernick shocked the league by retiring in his prime in 1966. Iconic protests of the ’60s and demands for Black power profoundly impacted Brown and how he prioritized football. More than a half century later, renewed demonstrations are prompting some modern Black athletes to value Black lives more than white ballgames.

Gus T. Renegade hosts “The Context of White Supremacy” radio program, a platform designed to dissect and counter racism. For nearly a decade, he has interviewed and studied authors, filmmakers and scholars from around the globe.