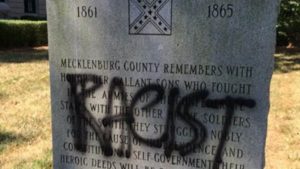

A North Carolina confederate memorial vandalized in 2015. (Source: WSOCTV.com)

The battle to remove confederate monuments reignited last month after a group of white supremacists gathered in Charlottesville, Virginia, to “protect” a statue of Confederate commander Robert E. Lee. Clashes during the weekend reached a boiling point after one white supremacist rammed his car into a crowd of counterprotesters, killing Heather Heyer and injuring more than a dozen others.

The rally to protect the statues had the opposite effect, as the Charlottesville City Council voted to remove a monument to Confederate General Stonewall Jackson and relocate the Lee monument this week. Monuments in Baltimore, Austin and other cities have come down, while actions for dozens more to be removed are under way.

Recognizing that naked appeals to racism and white supremacy are losers in the court of public opinion, defenders of keeping monuments to the Confederacy sometimes invoke the need to preserve history to maintain the status quo. President Donald Trump did as much in the wake of Charlottesville. “Sad to see the history and culture of our great country being ripped apart with the removal of our beautiful statues and monuments,” Trump tweeted. “You can’t change history, but you can learn from it.”

And every now and then, people who appear to be of good conscience parrot the erasing history talking point. Which is what Wall Street Journal columnist and former Reagan speechwriter Peggy Noonan did in a recent tweet. “My thinking: you can’t erase history, can’t remove it, can’t hide it in the corner. You must face it, discuss it,” she wrote.

Noonan, on the surface, is correct. We should not erase history. And we should face and discuss it. That is not, however, an argument for preserving monuments. Quite the opposite.

Spend enough time in the South and you’ll quickly realize the region is almost inseparably linked with systemic racism, including the Confederacy. People jokingly refer to the Civil War as the “War of Northern Aggression,” Confederate flags fly, and Confederate Memorial Day is observed in eight states.

There’s little doubt that Noonan would balk at being called a racist. While the defense of Confederate monuments, even under the guise of history, doesn’t make her a racist, she is guilty of defending racist ideas by proxy. That’s because the Confederacy, its leaders and soldiers cannot be divorced from racism.

Slavery is explicitly mentioned in Article One, Section Nine of the Confederate Constitution: The importation of negroes of the African race from any foreign country other than the slaveholding States or Territories of the United States of America, is hereby forbidden; and Congress is required to pass such laws as shall effectually prevent the same.

Again, in Article One, Section Nine (Two): “Congress shall also have power to prohibit the introduction of slaves from any State not a member of, or Territory not belonging to, this Confederacy.”

And again in Section Nine (Four): “Congress shall also have power to prohibit the introduction of slaves from any State not a member of, or Territory not belonging to, this Confederacy.”

The “slaveholding states,” as South Carolina referred to them in its declaration of secession, each laid out in no uncertain terms that white people and Black people could not be equal, something The Atlantic’s Ta-Nehisi Coates noted in 2015.

Arguments to protect history almost presuppose that confederate monuments were erected in the immediate aftermath of the war. If this were so, Noonan would have more of a case to make. It is not. As the History Channel notes in the aptly titled “How the U.S. Got So Many Confederate Monuments,” early commemorations were simple markers to fallen Confederate soldiers. The majority of the monuments were erected between “between the 1890s and 1950s, which matches up exactly with the era of Jim Crow segregation.”

Arguing that Confederate monuments should be left standing so as not to erase history isn’t facing history, it’s bastardizing it.

The South has gone to great lengths to romanticize and sanitize the era of our nation’s original sin. From the Sons of Confederate Veterans calling fallen soldiers of the Confederacy people who “personified the best qualities of America,” to the place “Gone With the Wind” holds in cinematic history, to the Texas board of education voting to teach that slavery was a “side issue” to the Civil War.

So if we are to teach, face and discuss history, as Noonan would like us to do, let’s do it.

Let us talk about how brutal slavery actually was. Let us talk about the more than 10 million Africans who were stolen from their homelands and dispersed throughout the Americas and Caribbean. Let us talk about the brutality inflicted upon the Black body by way of rapes, whippings and lynching.

Slavery and the makings of the Confederacy are rooted in racist violence visited upon the Black body by men who deemed the Black body physically superior enough to withstand grueling work but mentally inferior enough to live a life in servitude to white people. The monuments themselves have brought about violence on Black communities like Charlottesville, where Black neighborhoods were demolished to make room for citizens to reminisce on racism.

In a recent reminder that the original intent in erecting the majority of the monuments was to send a message to Black people, a Republican lawmaker stated that a Democratic lawmaker who is calling for the removal of Confederate monuments in Georgia might “go missing.”

If we are to live up to our highest ideals that all people are created equally, it is both foolish and counterproductive to honor men who literally fought to the death to preserve the idea that all people were not.

And to those who would argue that removing monuments is erasing history and eliminating teachable moments?

There are these things called books.

AJ Springer is a writer, communications pro, nerd and nomad. You can find him on Twitter @JustAnt1914 discussing current events, combat sports, pop culture and the finer points of pro wrestling. He makes his home in Washington, D.C.