Sounding as if she were describing a mafia hit, Donna Rogers-Beard said Clayton, Missouri’s Black “community was slowly suffocated and then finally snuffed out.” Rogers-Beard, a retired Clayton educator, and other Clayton citizens describe this mid-20th century expulsion in the new documentary film “Displaced & Erased.” Filmmaker Emma Riley exhibits how hundreds of Black residents, many of them homeowners, were methodically ejected from the region beginning in the 1950s. Urban renewal (infamously rebranded “Negro removal”) campaigns nonviolently compelled Black residents to leave and compensated them with market value for their property. City planners plotted an agenda for a prosperous new town, that, according to recent census data, has fewer than 10 percent Black citizens today. Rogers-Beard and scores of former residents described tremendous anguish about being forced to abandon prime property. Nestled minutes beyond the St. Louis city limits, Clayton is now a plush, commercial, nearly all-white enclave.

The eviction of Clayton’s Black inhabitants is part of a pattern in American history of repeated instances of often violent mass expulsions of Black people. The evictions and killings are censored from history, and the Clayton removal is only a more recent illustration of Blacks being wiped off a land.

Pulitzer prize-winning journalist Elliot Jaspin devotes a book to the history of racial cleansings but was forced to limit his work to a dozen of the “worst of the worst” incidents. In “Buried in the Bitter Waters: The Hidden History of Racial Cleansing in America,” Jaspin concludes there were more than 260 incidents where whites violently forced all Black people to flee an entire county. Jaspin’s tally omits nonviolent or small-town removals like Clayton, although he concedes hundreds of these “lesser” cleansings occurred.

A linchpin of Jaspin’s book and the Clayton documentary is white lies. Riley describes this deception as “deliberately leaving information out.” Years after locales like Clayton, Mo., and Forsyth County, Ga., (one of the “worst of the worst” racial cleansings in “Bitter Waters”) were melanin-free, Jaspin submits, “The white community would construct a lie.” As opposed to acknowledging that grandma and grandpa were racist goons who criminally ejected, or killed, legions of Black people, many white descendants offer bogus histories about voluntary, cordial departures of Black residents. Jaspin believes the lies absolve whites of guilt for the ransacking of Black people and further obscure Black property claims and legitimate requests for restitution.

In 2006, the Wilmington Race Riot Commission published findings to offset more than a century of constructed lies about the November 1898 purge of Wilmington, North Carolina. The New York Times provides a tidy summation of their findings: “Scores of black citizens were killed during the uprising — no one yet knows how many — and prominent Blacks and whites were banished from the city under threat of death.”

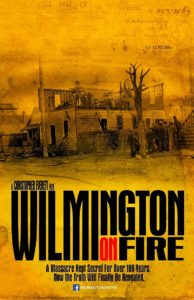

Christopher Everett’s documentary, Wilmington on Fire, examines the 1898 purge of Black residents in North Carolina.

Filmmaker Christopher Everett, a North Carolina native and creator of the documentary “Wilmington on Fire,” believes the untold number of Black casualties could top a thousand. Highlighting that Wilmington was a majority-Black town at the time of the massacre, Everett cites census data showing Wilmington lost half its Black population in the year following the “cleansing.”

“You had thousands of people that were exiled, but the population change was too drastic for just a hundred or a couple hundred people to get killed,” says Everett.

Texas native E.R. Bills was inspired to investigate the 1910 slaughter and expulsion of Black citizens from Slocum, Texas because of the dubiously low numbers of casualties reported. The conservative estimates of two dozen fatalities or fewer strongly clashed with his extensive research, which includes testimony from the white sheriff at the time of the massacre. Bills says the lawman reported, “There are Black bodies everywhere. Mobs of white people went around killing as many Black people as they could find and run down.” The sheriff’s record and corresponding mass grave sites compelled Bills to conclude the number of Black casualties could easily exceed two hundred.

While writing “The 1910 Slocum Massacre: An Act of Genocide in East Texas,” Bills worked with Constance Hollie-Jawaid, whose great-grandfather was a Slocum business owner and a victim of the massacre and expulsion. While advocating for a historical marker recognizing the assault on Black Texans, Hollie-Jawaid said that some whites thought her ancestor was “uppity,” and used the purge to return him to “his place.”

“They spread rumors and lies, and killed members of my family. Shot and wounded members of my family. And took the granary, the mercantile store, and seven hundred acres of prime fertile land in east Texas. And Texas still refuses to give it back,” said Hollie-Jawaid.

Jaspin reminds us that these expulsions happened more than 260 times.

When describing the long-term economic violence of the Clayton eviction, Emma Riley told St. Louis Public Radio, “This has greater implications for how wealth is transferred from generation to generation because these weren’t just Black people who were renting. They were property owners.”

Underscoring the pattern, John Hopkins University historian N.D.B. Connolly notes similar financial plunder in the 1921 Tulsa, Oklahoma slaughter, where approximately 300 people died according to the 2001 Tulsa Race Riot Commission. In addition to the bloodletting, Connolly says whites “burned whatever proof existed about the land owners.”

Connolly adds that the confiscation of Black land undergoes upgrades. What was smash and loot in 1898 Wilmington, becomes “eminent domain” and “urban renewal” in 1950 Clayton. But the result is the same. “Negro (wealth) removal.”

“Displaced and Erased” was screened at the St. Louis Filmmakers Showcase near the three-year anniversary of the shooting death of Ferguson’s Michael Brown Jr. This year is also the centennial anniversary of the 1917 East St. Louis “race riots,” where the number of casualties remains unknown. All three tragedies reflect the unending racist violence targeting individual, collective, and generational Black well-being.

Gus T. Renegade hosts “The Context of White Supremacy” radio program, a platform designed to dissect and counter racism. For nearly a decade, he has interviewed and studied authors, filmmakers and scholars from around the globe.