Credit: HBCU Lifestyle

They have existed among us for more than a century. They emerged at a time when there was a particular need for unity, affirmation and self-determination given the dominant society’s denial of the inherent value of our community. They’ve facilitated a sense of identity and belonging. They’ve played a role in our educational and career trajectories. They’ve provided us active and supportive networks of human resources. They’ve cemented lifelong relationships relevant to our personal and professional success.

They helped shape some of the greatest minds our community has produced, among them Shirley Chisholm, Zora Neale Hurston, Martin Luther King Jr., Toni Morrison and Thurgood Marshall. They go by Greek-lettered monikers like Alpha Kappa Alpha and Alpha Phi Alpha; Delta Sigma Theta and Iota Phi Theta; Kappa Alpha Psi and Omega Psi Phi; Phi Beta Sigma, Sigma Gamma Rho and Zeta Phi Beta.

Few would question whether Black Greek Letter Organizations, or BGLOs, have had a positive impact on the plight of African Americans. However, given the uncertain times we now live in, some question if these organizations could have a greater effect on our community as a whole.

“On the whole, we are not having a major impact on our communities or even on our campuses,” says Dr. Walter M. Kimbrough, president of Dillard University and author of Black Greek 101: The Culture, Customs and Challenges of Black Fraternities and Sororities. An active member of Alpha Phi Alpha, Kimbrough notes there are BGLO local chapters “doing some really good things to develop their communities” before acknowledging a recent national initiative promoting awareness and support for Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) which Dr. Kimbrough supports. Still, he feels the national organizations today are “enamored with this idea that we are service organizations when, really, we are social groups.”

In terms of results, contends Kimbrough, “you aren’t going to find any major initiatives that the groups are doing nationally where people can see there’s been a significant communal impact.”

Others have a different take. “BGLOs are still thriving on college campuses so, obviously, they are doing something right,” says Koya Perez, community service chairperson for Alpha Kappa Alpha (AKA) at Delaware State University. The senior mass communications major had heard little about BGLOs prior to college but was attracted because of their impact on campus and adherence to a tradition of “keeping sisterhood, brotherhood, scholarship and community service alive.”

In her organizational role, Perez oversees monthly service activities, including the mentoring of young girls, and “Community Impact Days” incorporating timely themes ranging from Alzheimer’s support activities to childhood hunger awareness. These activities are consistent with AKA’s five program targets for service, a national guide for community efforts in the areas of Educational Enrichment, Health Promotion, Family Strengthening, Environmental Ownership and Global Impact.

“As members of Black Greek organizations it’s important to keep our traditions alive and remember why we were created in the first place,” says Perez.

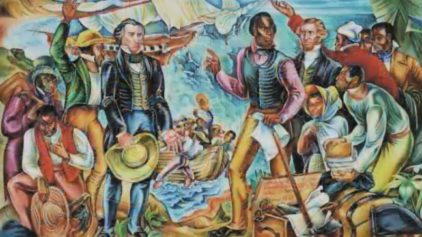

Long before there were any Black Greek traditions, and back before there were even Greek societies themselves, Africans constructed the quintessential societies of learning, intellect and refinement in ancient lands like Kush and Kmt. In Kmt—the oldest recorded and arguably the highest civilization to ever grace the earth before faltering, ultimately being conquered by European outsiders and renamed “Aegyptos” or “Egypt”— that included social groups akin to today’s Greek societies whose initiates for the priesthood were subjected to extraordinary intellectual and physical trials aimed at conquering fear and sparking profound growth and transformation. This ancient model was later replicated in a variety of Western institutional expressions ranging from core religious and educational constructs to civic societies and fraternal organizations.

In America by the end of the 19th century there was a need among Negro students and professionals to fraternize in an affirming and self-supporting way. Starting in 1903, there were a few attempts to organize on college campuses, including the short-lived existence of Alpha Kappa Nu at Indiana University. In 1904, unlike the subsequent introduction of the major college-based Black Greek societies, or “Divine Nine,” Sigma Pi Phi—more commonly recognized as “The Boule”—was founded in Philadelphia as an exclusive vehicle for established professionals.

With the 1906 founding of Alpha Phi Alpha at Cornell University, these organizations began serving large numbers of Black college students seeking affirmation, camaraderie and service to their community. The 20th century would eventually witness the impact of such organizations as its well-positioned members in the Harlem Renaissance, civil rights movement and national politics would help transform society at large.

While some feel these transformative characteristics are no longer a tangible aspect of BGLOs, there has been some recent activity that could challenge such notions. Within AKA’s aforementioned five program targets for service, the sorority launched its national initiative promoting awareness and support for HBCUs and continued a youth enrichment program aimed at motivating and engaging high school students. Delta Sigma Theta runs a Social Action Commission that promotes the organization’s legislative initiatives and active chapter involvement in local, state, and national issues. The Deltas also operate ongoing programs serving at-risk youth and facilitating their college and career readiness. Numerous BGLOs offer a variety of programs and agendas aimed at improving youth and community outcomes.

Kimbrough feels such efforts are commendable but, given the tumultuous times our community finds itself in, just not enough. He mentions a number of possible national efforts for BGLOs including more comprehensive mentoring services for youth and the establishment of partnerships with school systems to provide students with resources, preparation and after-school programming. “I just think there are lots of needs in our community that we have not been strategic enough to say, ‘Let’s meet those needs.’ ”

Given their educated membership bases, resources and reach, the capacity for BGLOs to do more on a national level—individually or collectively—is apparent. They have the potential to create institutions in the community that go beyond current models of community service and networking.

“We’ve got to find ways to be involved in a much more meaningful way,” insists Kimbrough, be it as organizations, or “even if all of our members did certain things individually.”

Either way, he adds, “that would be great because it would mean we are living out the creed of our organization.”