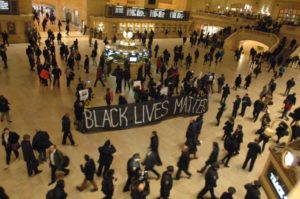

NYPD officers posed as Black Lives Matter activists in order to gain information about protests. (Photo by Sam Costanz/For New York Daily News)

The NYPD’s sweeping surveillance of mass protests following the 2014 death of Staten Island man Eric Garner might ultimately prove problematic, according to new reports.

Recently released documents obtained by The Guardian revealed that undercover NYPD officers infiltrated small groups of Black Lives Matter activists and gained access to their private text messages. The documents, primarily emails bounced between undercover officers and other NYPD officials, followed discoveries that the department regularly filmed BLM activists, then deployed undercover personnel to monitor their demonstrations.

The reports were produced in response to a February court filing ordering the NYPD to hand over any and all surveillance files on BLM activists who’d gathered at Grand Central terminal in the wake of Garner’s death, The Guardian reported.

In one of the emails, officials described how undercover officers were able to pose as BLM protesters, giving them sweeping access to details on the whereabouts and plans of fellow demonstrators. A NYPD official noted that an undercover cop was tucked within a group of seven activists on their way to Grand Central Station in 2014, allowing officers posed as trusted organizers to pluck pertinent information regarding upcoming demonstrations.

The names and locations of specific protesters were also listed in the emails, along with screenshots of organizers’ group text chats with information about protests. The NYPD’s ability to gain access to such personal messages suggest that undercover officers were either trusted enough to take photos of activists’ phones or were themselves members of a private planning messaging group.

“That text loop was definitely just for organizers, I don’t know how that got out,” Elsa Waithe, a BLM organizer, told The Guardian. “Someone had to have told someone how to get on it, probably trusting someone they had seen a few times in good faith. We clearly compromised ourselves.”

The NYPD’s surveillance tactics have been repeatedly challenged, with legal experts arguing that officers’ secret monitoring of activists violates the Handschu Agreement of 1985, which prohibits indiscriminate police videotaping and photographing of public gatherings unless there’s clear evidence of unlawful activity.

“The documents uniformly show no crime occurring, but NYPD had undercovers inside the protests for months on end as if they were al-Qaida,” said David Thompson, an attorney of Stecklow & Thompson, who helped sue for the records.

Joseph Giacalone, a retired NYPD detective sergeant and current professor at John Jay College, questioned the ease of undercover officers’ ability to infiltrate a small group of protesters and learn their plans in such a short time.

“It would be pretty amazing that they would be able to get into the core group in such a short window of time,” Giacalone said. “This could have been going on a while before for these people to get so close to the inner circle.”

The retired detective also confessed it was common practice for officers to sniff out activist leadership during large demonstrations as part of their surveillance efforts.

“If you take out the biggest mouth, everybody just withers away, so you concentrate on the ones you believe are your organizers,” Giacolone said. “Once you identify that person, you can run computer checks on them to see if they have a warrant out or any summons failures, then you can drag them in before they go out to speak or rile up the crowd, as long as you have reasonable cause to do so.”

According to The Guardian, attorneys have since filed another complaint charging that the NYPD may have failed to release all of its surveillance files. For some protesters, however, the damage of having officers infiltrate their organizing efforts has already been done.

“In the first couple of months, we had a lot of people in and out of the group, some because they didn’t fit our style, but others because of the whispers that they were undercovers,” Waithe said. “Whether it was real or perceived, that was the most debilitating part for me, the whispers …

“It’s really hard to organize when you can’t trust each other.”