The groundbreaking report, which examined the federal records for roughly 5,300 fatal pursuits since the government began tracking the races of victims killed in car wrecks, highlighted another aspect of racial bias in America’s policing that has remained largely ignored.

The investigation revealed that the racial variation among those killed in high-speed police chases almost exactly mirrors the racial disparity in fatal police shootings. This is especially telling since African-Americans comprise just 13 percent of the U.S. population, yet account for 28 percent of those killed in police pursuits where the race of the victim was known.

Among the study’s other key findings:

- Blacks have been disproportionately killed in police pursuits every year since 1999. On average, 90 Black people died each year in police chases, nearly double what would be expected based on their percentage of the population.

- Deadly pursuits of Black motorists were twice as likely to start over minor offenses or nonviolent crimes. In 2013 and 2014, nearly every deadly pursuit triggered by an illegally tinted window, a seat-belt violation or the smell of marijuana involved a Black driver.

- Black people were more likely than whites to be chased in more crowded urban areas, during peak traffic hours and with passengers in their cars, all factors that can increase the danger to innocent bystanders. Chases of black motorists were about 70 percent more likely to wind up killing a bystander.

“This is not giving someone a traffic ticket,” said Jack McDevitt, director of Northeastern University’s Institute on Race and Justice. “This is people dying. The cost of having small disparities is huge because you’re ending up with loss of life.”

The USA Today report comes amid heightened racial tensions surrounding a string of fatal police shootings of African-Americans over the past years. Heated protests have erupted in cities like Ferguson, Missouri, Baltimore and Charlotte, with many angered and dissatisfied over law enforcement’s unfair, and oftentimes lethal, treatment of Black Americans.

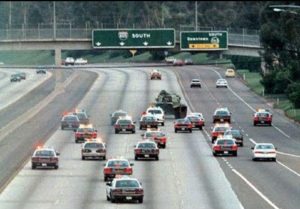

The study reported that car pursuits are among the most dangerous police activities — one that has killed more than 6,200 people since 1999. Almost 30 percent of those killed were African-American.

Eleven of the nation’s leading researchers on race and policing who weighed in on the USA Today analysis argued that the report’s findings required additional scrutiny to determine if and how much of a role racial bias played in the deadly police activity.

Some police officials have asserted that racial bias doesn’t influence an officer’s decision to pursue a suspect. Rather, they attributed the disparity in fatal pursuit accidents to police spending more time patrolling high-crime neighborhoods.

Because measuring racial bias can be tricky, researchers moved to measure the number of fatal pursuits in the daytime vs. the nighttime, when police are not as clearly able to determine someone’s skin color. The news organization found that in daylight, 31 percent of the drivers involved in deadly police chases were Black, while in darkness, 21 percent were Black.

“It’s a provocative difference,” said Jeffrey Grogger, a University of Chicago professor who conducted the first study of traffic stops in daylight and darkness. “The pattern is really striking.”

Moreover, the report revealed that for every 100,000 African-Americans in the U.S., four were killed in police chases in the years between 1999 and 2015. For every 100,000 people who aren’t Black, 1.5 were killed, USA Today reported.

Though the report didn’t show that officers outwardly considered a suspect’s race when contemplating whether or not to pursue them, it did suggest that the suspect’s race could influence how police react to said suspect.

Delores Jones-Brown, director of the John Jay College Center on Race, Crime and Justice, echoed the study’s findings, stating, “Even when people think they’re not using race in decision-making in law enforcement, there is this way we as humans see people — particularly black people — as criminal or potentially criminal.”