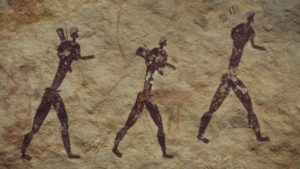

SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

Hints of an early exodus of modern humans from Africa may have been detected in living humans.

People outside Africa overwhelmingly trace their descent to a group that left the continent 60,000 years ago.

Now, analysis of nearly 500 human genomes appears to have turned up the weak signal of an earlier migration.

But the results suggest this early wave of Homo sapiens all but vanished, so it does not drastically alter prevailing theories of our origins.

Writing in Nature, Luca Pagani, Mait Metspalu and colleagues describe hints of this pioneer group in their analysis of DNA in people from the Oceanian nation of Papua New Guinea.

After evolving in Africa 200,000 years ago, modern humans are thought to have crossed through Egypt into the Arabian Peninsula some 60,000 years ago.

Until now, genetic evidence has shown that today’s non-Africans could trace their origins to this fateful dispersal.

Yet we had known for some time that groups of modern humans made forays outside their “homeland” before 60,000 years ago.

Fossilized remains found at the Qafzeh and Es Skhul caves in Israel had been dated to between 120,000 and 90,000 years ago.

Then in 2015, scientists working in Daoxian, south China, reported the discovery of modern human teeth dating to at least 80,000 years ago.

An additional piece of evidence recently came from traces of Homo sapiens DNA in a female Neanderthal from Siberia’s Altai mountains. The analysis suggested that modern humans and Neanderthals had begun mixing around 100,000 years ago — presumably outside Africa.

In order to reconcile this evidence with the genetic data from living populations, the prevailing view advanced by scientists was of a wave of pioneer settlement that ended in extinction.

But the latest results suggest some descendants of these trailblazers survived long enough to get swept up in the later, ultimately more successful migration that led to the settling of Oceania.

“The first instance when we thought we were seeing something was when we used a technique called MSMC, which allows you to look at split times of populations,” said co-author Dr. Mait Metspalu, director of the Estonian Biocentre in Tartu, told BBC News.

His colleague and first author Dr. Luca Pagani, also from the Estonian Biocenter, added: “All the other Eurasians we had were very homogenous in their split times from Africans.

SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY: Fossil evidence from Israel, like this individual from Qafzeh cave, suggests modern humans were already living outside Africa at least 90,000 years ago.

Read more here.