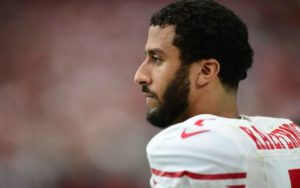

By sitting down during the national anthem and standing up for justice, Colin Kaepernick is testing the limits of the Black athlete to engage in effective social protest. Ultimately, this is a test for the Black community, should it wish to take on the challenge. If Kaepernick stands alone on this, then he will certainly fall, and Black people in the aggregate stand to lose. But if other players and the community as a whole have this man’s back, we protect ourselves from the onslaught.

Are the days of the high-priced slave over? And what would it look like if Black athletes stood up in defense of their fellow player, and proclaimed that it is a new day?

“I am not going to stand up to show pride in a flag for a country that oppresses black people and people of color,” Kaepernick told NFL.com. “To me, this is bigger than football and it would be selfish on my part to look the other way. There are bodies in the street and people getting paid leave and getting away with murder.”

The 49ers issued a statement in response to Kaepernick’s decision. It said, in part, “In respecting such American principles as freedom of religion and freedom of expression, we recognize the right of an individual to choose and participate, or not, in our celebration of the national anthem.”

There was good reason for Kaepernick to sit down. That anthem — written by Francis Scott Key, a slave owner who owned up to 20 Black people, according to The Baltimore Sun — is one that glorifies slavery, which is in itself an outrage. The third verse of the “Star-Spangled Banner,” usually left unsung, is a celebration of the murder of slaves who fought with the British in the War of 1812 — that attempt by the U.S. to seize Canada from the British.

“No refuge could save the hireling and slave / From the terror of flight or the gloom of the grave,” that verse reads, “And the star-spangled banner in triumph doth wave / O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave.”

Like Kaepernick, Jackie Robinson reflected on the national anthem during his first World Series in his autobiography, “I Never Had It Made.” The first Black man to enter the all-white space of Major League Baseball said the anthem was a theme song for a drama called The Noble Experiment.

“Today, as I look back on that opening game of my first world series, I must tell you that it was Mr. Rickey’s drama and that I was only a principal actor.” He added: “As I write this twenty years later, I cannot stand and sing the anthem. I cannot salute the flag; I know that I am a black man in a white world.”

And it appears the onslaught against the 49er is just beginning. Some of the backlash is coming from Black critics. Rodney Harrison, former NFL player and an NBC analyst, apologized for claiming Kaepernick is not Black and does not understand racism and what Black people and Black young men face. But a sampling of comments from NFL executives tells the real story, as reported by Mike Freeman of The Bleacher Report:

“I don’t want him anywhere near my team,” one front office executive said.

“He’s a traitor.”One executive said he hasn’t seen this much collective dislike among front office members regarding a player since Rae Carruth.

Another said that if an owner asked him to sign Kaepernick, he would consider resigning, rather than do it.

Apparently, in the minds of some NFL executives, Black protest — which should be protected by the First Amendment — is a crime akin to murder and other felonious offenses.

Consider that Rae Carruth, the former Carolina Panther wide receiver, is in prison for conspiring to murder the woman who was pregnant with his child. And quarterback Ben Roethlisberger of the Pittsburgh Steelers — who was accused of raping two women, and apparently lives in a glass house — believes he has the moral authority to express his disappointment with Kaepernick, who should be thankful that people gave their lives so that he can play football. This is what Black people face when they do not realize their power and fail to channel it.

Further, Harry Belafonte offered a fitting commentary on the NFL quarterback:

“The fact that these people have all these ‘how dare you speak out against lynching’ and all the things that racism stands for, or the conclusions to racist acts permit. I think it’s a statement about America,” Belafonte said on “News One Now. “What I would love to see, is a few hundred other Black athletes take that as a symbol,” he added. “It doesn’t affect the game. It doesn’t affect the way that it’s going to be played, it just tells you a lot about what the people on the field are thinking in their every waking moment.”

If 100 Black athletes heed Belafonte’s call and step up by sitting down with Colin Kaepernick, they can provide a template for Black activism in professional sports. Professional football and basketball in particular are operated like modern-day plantations, with predominantly white owners and management presiding over Black talent — 68 percent in the NFL and 76 percent in the NBA. Based on the power dynamics in the sport, white executives have made a calculation that they can say whatever they want about Black people without facing consequences. If Kaepernick stands alone, they can continue to speak with the utmost confidence, with no motivation to change their stance for fear of reprisal. The NFL power structure will take him down, and run roughshod over him, as a lesson to other players who dare get out of line.

However, the prospect of displaying Black collective power is ripe with possibilities. The league would not survive without their labor, and untold billions of dollars are on the line, as these players must emphasize. The power of Black athletes standing together was on display in Missouri, when the predominantly African-American University of Missouri football team participated in a players’ strike to protest campus racism and demand the ouster of the university administration. In that regard, they succeeded, or at least the university was forced to meet the Mizzou team halfway, however reluctantly, because of the millions of dollars that were hanging in the balance.

Ultimately, as Frederick Douglass said, “Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did and it never will. Find out just what any people will quietly submit to and you have found out the exact measure of injustice and wrong which will be imposed upon them, and these will continue till they are resisted with either words or blows, or with both.”

When Black gladiators stand up to the empire, then we can begin to address the economics of the game, and demand that more Black-owned businesses receive contracts with the NFL or the NBA. Players can demand that a certain percentage of the billions in profits reaped from the sweat of their labor are redirected back into the Black community to support our banks, schools, charities and other institutions. Further, Black athletes can demand that the reporters who cover the game look more like the players themselves. Journalism, in this case sports journalism, is an overwhelmingly white proposition, which is unacceptable. As was reported in The Undefeated, while the locker rooms are Black, Black journalists are scarce, which means we are missing a great deal of meaningful, contextualized reporting because of it.

Surely, forcing the hand of the master is a daunting proposition for some. After all, leaving the plantation — psychologically — is frightening, and these players are concerned they will lose their contracts, their paychecks. And while players such as Cam Newton have a right to sit on the sidelines and proclaim that we’re all the same color, history has proven that society will not do right by you just for the sake of it. Rather, as was always the case, Black people are compelled to fight for what they want, so that white people are able to see them as human beings.

Colin Kaepernick has much on the line, but his own personal gesture demonstrates that no one is at rest when systemic racism still exists. As long as injustice reigns supreme, your money is not safe. Slaves are never safe on the plantation, and there will be no sense of security until we change the game in its entirety through a collective effort.

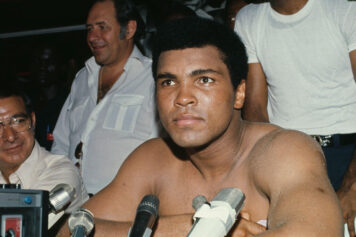

That spirit of unity that is required today was on display nearly 50 years ago, when the most prominent Black athletes gathered in Cleveland to support Muhammad Ali, who lost his boxing title and his license for refusing to serve in the Army in Vietnam. Ali, who is loved and admired in death, was reviled and vilified in his day.

“What should horrify Americans is not Kaepernick’s choice to remain seated during the national anthem, but that nearly 50 years after Ali was banned from boxing for his stance and Tommie Smith and John Carlos’s raised fists caused public ostracization and numerous death threats, we still need to call attention to the same racial inequities,” said Kareem Abdul-Jabbar in an op-ed in The Washington Post, also referring to the Black medalists at the 1968 Summer Olympics. “Failure to fix this problem is what’s really un-American here.”

The questions that arise are whether we care more about empty, forced patriotism or the injustices that remain, and whether we are more outraged by protests than the racism and racial violence that sparked those protests in the first place.

Today, some may regard professional athletes as today’s version of high-priced slaves who are supposed to shut up, run and throw the ball, and entertain the masses. As they earn their millions, they are certainly generating billions for their masters. Once they band together, stand up and take control of their destiny, they will realize their power.

And the Colin Kaepernicks who arise in our midst will not be alone.