There is a saying that one size doesn’t fit all. And apparently this holds true for medical treatments for prostate cancer. Hormone therapy to combat the disease may pose a higher risk of death in Black men, according to a new study.

The study, conducted by researchers at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, examined the medical records of 1,500 men from the Chicago Prostate Center, as The Washington Post reported. These men, of which 7 percent were Black, had low-to-intermediate risk prostate cancer and were treated with Androgen deprivation therapy, or ADT. ADT is a hormone treatment used to reduce malignant tumors in the prostate by lowering a patient’s testosterone levels. Androgens, or male hormones, are required for the proper growth of the prostate, which helps in the production of semen. However, androgens also promote the growth of prostate cancer. The hormone therapy used for prostate cancer, also known as androgen suppression therapy or androgen deprivation therapy, can reduce androgen production in the testicles and block the production of androgens in the body, according to the National Cancer Institute.

The Brigham and Women’s research found that Black men had a 77 percent greater risk of death than their white counterparts, and had a higher risk of death as early as four months after treatment. Further, Black men tended to be younger, were treated later, and had a higher incidence of other health issues, as The Post reported.

Black men have a consistently higher risk of death from prostate cancer. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, between 1999 and 2013, Black men were more likely to die from prostate cancer than any other racial or ethnic group, followed by white, Hispanic, American Indian/Alaska Native, and Asian/Pacific Islander men.

However, in the BWM study, the cancer itself did not kill these African-American men. Rather, researchers say the deaths appear to be linked to cardiovascular problems prior to their diagnosis, with ADT increasing the risk of a heart attack.

“When African-American men were exposed to an average of only four months of hormone therapy, primarily used to make the prostate small enough for brachytherapy, they suffered from higher mortality rates due to causes other than prostate cancer than non-African American men,” said Konstantin Kovtun, MD, a resident at BWH who worked on the study, as reported by News-Medical.net. Brachytherapy is a cancer treatment in which radioactive implants are placed directly into the tissue. “This leads us to believe that there may be something intrinsic to the biology of African-American men that predisposes them to this increased risk of death and that this deserves further study.”

“These results show that careful consideration should be taken by physicians when recommending treatment for low or favorable-intermediate prostate cancer, a cancer that very few men die of even without treatment,” added Anthony D’Amico, MD, PhD, chief of Genitourinary Radiation Oncology at BWH. “There is no evidence that ADT followed by brachytherapy increases the chance of cure in comparison to other treatments, such an external beam radiation therapy alone, in these men with favorable risk prostate cancer. The subsequent risks of ADT, specifically linked to African-American men, deserve further study,” he added. The research findings were published in the August 4, 2016 issue of Cancer.

Atlanta Black Star has reported that clinical trials in the U.S. do not reflect the diversity of the country. Although these medical tests determine what medications will be given to the general public, Black and brown people generally are not participants in these clinical trials. And given the country’s shameful history of using Black people as human guinea pigs in medical experiments, African-Americans are understandably reluctant to participate in the research. As a result, white participants, especially white men, predominate in the studies, even as research has shown that Blacks, Asians and others respond differently to medications when compared to whites.

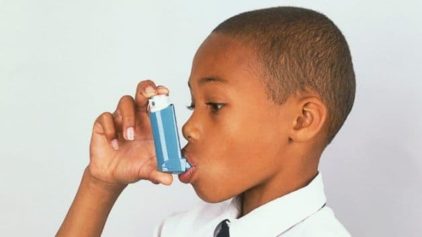

A prime example of the consequences of excluding Black people from clinical trials involves the treatment of asthma. Most genetic and environmental studies on asthma in children have focused on white patients, raising serious questions as to whether the known risk factors for asthma even apply to Black children at all. While 14 percent of Black children have asthma, only 8 percent of white children have the condition. Meanwhile, a study of 800 Black asthmatic children found that only 5 percent of the genetic variations associated with asthma in whites were present in Blacks.