Dunbar National Bank, Harlem, NY, 1920

The Black bank has played an important role in funding Black entrepreneurs, businesses and institutions, sustaining the Black community and helping individuals when other banks turned a blind eye. This Juneteenth–the commemoration of the end of slavery and the beginning of freedom and independence for African-Americans–provides an opportune time to examine the role of that Black financial institutions have played and continue to play, the ways in which integration impacted the economic ecosystem, and the challenges and opportunities facing Black banks.

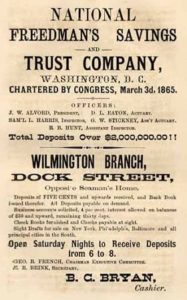

Freedman’s Savings Bank on Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, D.C.

In 1865, following the Civil War, the Freedman’s Savings and Trust Company, also known as The Freedman’s Bank, was established by Congress, along with the Freedmen’s Bureau, to aid newly emancipated Black people. Frederick Douglass became its president. Although the bank was short-lived—it folded in 1874 due to mismanagement, fraud, debt and the Panic of 1873 that swept the nation. According to the Partnership for Progress, 61,131 African Americans had deposited $2.9 million in the bank.

Meanwhile, during the era of Jim Crow segregation, Black-owned banks were crucial in the economic growth and development of communities throughout the country, with the African-American community of Tulsa, Oklahoma–also known as Black Wall Street–as a most prominent example.

According to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, there were over 130 African-American owned banks between 1888 and 1934. That number dwindled to 48 in 2001, and only 22 today. In contrast, there are 30 Hispanic banks in the U.S., 68 owned by Asian Americans, and 18 Native American institutions. Far fewer of these financial institutions–which have been known to provide a lifeline to Black community over the years–are in operation, at a time when they are needed more than ever. And the reasons for the drop in the number of African-American banks and the breakdown of the Black economic system are numerous, including technology, financial regulations, the Great Recession–and integration, or at least the ways in which the Black community has responded to integration.

Advertisement for the Freedman’s Bank, Haddock, T.M., compiler. Haddock’s Wilmington, N. C.

“Minority and CDFI banks (federally-insured community development financial institutions) play a vital role. Your mission is important. You provide responsible banking services to those who might not otherwise have access to a bank,” said FDIC Chairman Martin Gruenberg, as reported on the corporation’s website. “And, you serve some of the most challenging markets in the country. One way we can contribute to your efforts is by conducting research specifically on MDI and CDFI institutions—to better understand the role they play in our financial system and in our communities.”

“There has been a decline in banks in general. There also has been a decline in community banks that were the size of a lot of the Black banks that went out of business,” Teri Williams, the President and Chief Operating Officer of OneUnited Bank, the largest Black bank in the U.S., told Atlanta Black Star. “Part of what we realized is there were a lot of Black banks with a great mission, but they didn’t have the economies of scale to invest in new technology…and we acquired four banks and combined them into one.” Williams noted that Black banks tend to be smaller, unable to invest in technology, and unable to meet the financial costs that come with the higher demands of federal regulation and compliance.

“What I would also say…is what drives a bank in terms of profitability and stability is having deposit dollars. If you ask the Black community, ‘Where do you put your dollars?’ most will say they put it in the larger banks. And it is difficult for Black banks to attract dollars from their own community,” she said.

The success of African-American financial institutions and the Black community comes down to an issue of dollars and economic sense. Williams believes many in our community do not understand the role of a bank. “The role of a bank is to be a recycler. What that means is people place deposits into the bank, and the role of the bank is to take those funds to the community, to build wealth or for buying a home,” she said. “That in turn results in additional deposits that go into the bank, and the recycling goes on.”

Williams notes that other ethnic groups do a much better job than we do of recycling in their community. “In the African-American community, our dollars leave the community in 6 hours,” she said, echoing the points made by Maggie Anderson in a TED x Baltimore talk in 2014. In contrast, Anderson points out, a dollar in the Asian community takes 28 days to recycle, and 19 days in the Jewish community. Meanwhile, only 2 percent of African-American buying power goes back into the community. However, if Black people were to increase spending within our own community from 2 percent to 10 percent, we would create 1 million new jobs, as Anderson discusses in her TED talk.

Examining at the issue of Black investment in the community another way, consider that OneUnited Bank, the largest Black-owned bank in America, has assets of $650 million. Meanwhile, based on FDIC data, the largest Hispanic bank–International Commerce Bank of Laredo, Texas–has $9.6 billion, while the largest Asian-American bank– Cathay Bank in Los Angeles–has assets of $13.2 billion. With $1.3 trillion in buying power, the African-American community can follow suit.

“As a community we have some explaining to do,” Williams emphasizes. “This is an area where we really need to start to understand and use our financial power more wisely.”

OneUnited serves the community differently, and arguably better than a majority-owned bank would, Williams said. For example, whereas people may think they have to settle for higher fees at a Black bank, that is not the case, Williams said. “Our rates are higher, our fees are lower, and we have 25,000 ATMs where you can get your money for free. So, in fact we have better services than national banks, and we have services that are targeted to meet the needs of our community than national banks” she said. One of those services is a “Second Chance” checking account, where people who have a CheckSystem record as a result of mismanagement of their checking account (think of a bad credit record, but within the context of a checking account) can open an account with OneUnited.

“We have a secured credit card, with a how to rebuild credit program,” Williams said, noting that the problem with the prepaid debit cards that are so popular are high fees that do not help build credit. “Because we realize if you have bad credit you can’t get a loan, your rates our higher, and lot of people in our community don’t know how to repair their credit,” she added. “We offer services that help the community as opposed to services where we make the most money.”

Despite the challenges facing Black financial institutions, there is room for growth, which makes Williams optimistic for the future. “As a community we need to invest in technology, which OneUnited has done, and the importance of technology is not just a Black bank issue, it is a community bank issue” Williams said, noting that community banks tend to have older customers and not as much of an investment in new technology. “Integration became an issue for Black banks 20 years ago. Today it is a different issue. There are opportunities and challenges today. OneUnited is attracting black customers from across the country. You can open an account with us anywhere in the 50 states. We have customers all over, because we have the technology where you can open an account wherever you are. You can even pay people by text,” the bank president noted. “Really for us what is happening today is fueling our growth, but if you are a small bank and you don’t have that technology–and that’s Black or white–then you’re losing business. Black people just happen to have more of those small banks” she added.

“We believe we need to start a movement to making our dollars matter. As long as we don’t recognize the value and importance of our dollars, we will not get the services and respect we deserve–similar to our vote. Just as we need to make our vote matter, we need to make our dollar matter,” Williams said. “Banks are going to become like Blockbuster. There is no need to go to Blockbuster, there is Netflix and Hulu, and unless you use that technology you are going to be obsolete,” she insists. “The future is bright, and people realize our money matters.”