“The Book of Negroes” Scene 1.58; EXT – Port Charles Town; They have arrived at their destination.

The new reboot of the miniseries “Roots” reminds us of the physical toll that slavery has taken on Black people. Slavery was an exploitative system that built global capitalism through the theft, kidnapping, torture and prison labor of millions of Africans.

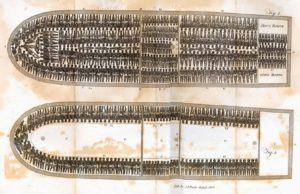

However, that process is and continues to be an intergenerational one, in which Black people have suffered psychic damage. The experiences of the dreaded slave ship dungeons of the Middle Passage–in which millions of souls still rest at the bottom of the Atlantic—the auction blocks, the rapes, whippings and lynchings, the slave patrols, the backbreaking and life-ending labor at gunpoint, the separation of families all inflicted psychological damage on the victims and their descendants. Though their trauma was profound, enslaved Black people had no mental health therapists available to them, no counselors to help them cope and heal. And the sickness was passed down to subsequent generations who, to this day, have not received the treatment they so desperately require.

Monnica Williams, Ph.D., director of the Center for Mental Health Disparities at the University of Louisville

Black people have post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD, and they may not even know it. “PTSD symptoms typically include intrusive thoughts about the trauma, avoidance of thoughts or reminders of the trauma, anxiety, concerns about safety, feeling constantly on guard, fears of being judged because of the trauma, and depression. Individuals may also have flashbacks and feelings of dissociation. Very severe PTSD can result in psychosis, and PTSD can be temporarily or permanently disabling,” Dr. Monnica Williams, clinical psychologist and director of the University of Louisville’s Center for Mental Health Disparities, told Atlanta Black Star. According to Williams–who is also a professor in the Department of Psychological & Brain Sciences and writes the “Culturally Speaking“ blog at Psychology Today –PTSD has particular significance in the Black community. “Symptoms specific to race-based trauma in African-Americans may include avoidance of white people, fears and anxiety in the presence of law enforcement, paranoia and suspicion, and excessive worries about the safety of family and friends.”

In a society in denial, racism is proclaimed dead and an historical phenomenon. Yet it is very much alive, as manifested in the behavior of Black folk. In her book, Post Traumatic Slave Syndrome: America’s Legacy of Enduring Injury and Healing, Dr. Joy DeGruy discusses the condition that serves as the title of her book:

Innocent and angry little boys threatened by a glance; proud parents reluctant to praise their children and feeling the need to inhibit their natural exploratory instincts; friends not being able to celebrate the successes of their peers; organizations torn asunder from within . . . and there’s more. Parents feeling the need to protect their children from the police. Issues of skin color and hair texture continuing to dominate discussions regarding beauty and physical preference. The excessive focus on material accumulation. People needing, wanting and dreaming, yet fearing they will not succeed. Most of all frustration. Frustration and anger, at times even rage, feelings that seem to dominate many of our lives. If you’re black and living in America, none of this may be news to you.

Dr. DeGruy argues that typically, society does not address the role of history in producing these negative behaviors and perceptions. African-Americans, she contends, adapted their behavior in order to survive chattel slavery, an example of “transgenerational adaptations associated with the past traumas of slavery and on-going oppression.”

“I think there is too much emphasis placed on racist individuals as opposed to the social forces that create racists. Everyone behaving a slightly racist way has a much more deleterious effect on Black people than a few people being very racist,” Dr. Williams said. “Racism is built into the power structures and institutions in our society, and White people are taught to propagate racism and not to see it. This process is maintained by pathological stereotypes and misinformation about Black people. White supremacy is a reaction to feeling one’s social status threatened by the advancement of African Americans.”

And while racial oppression has a psychological, multigenerational impact on Black people, it also leaves a biological and genetic imprint in its victims. In other words, research suggests the trauma is embedded in the DNA, changing one’s genetic makeup and becoming transferrable to subsequent generations.

According to the National Institutes of Health, chronic stress and exposure to stress hormones alter our DNA—not the gene sequence but rather gene expression. When we are under stress, we produce steroid hormones called glucocorticoids, which affect various bodily systems. Past studies have shown that these glucocorticoids alter the genes that control the HPA axis, which includes the hypothalamus and pituitary glands of the brain, and the adrenal glands near the kidneys. When the Fkbp5 gene is modified, this leads to PTSD, depression and mood disorders. Studies involving the descendants of Jewish Holocaust survivors under Nazi Germany found that these individuals had an altered Fkbp5 gene, along with PTSD, hypertension and obesity.

A 2008 study in the National Academy of Sciences found that people who were prenatally exposed to the Dutch famine of 1944-5 had an altered IFG2 gene—which plays an important role in human growth– 60 years later. Children of mothers who were pregnant during that famine developed a number of health problems such as obesity, diabetes, kidney damage and heart disease.

Dr. Farah D. Lubin–Associate Professor in the Department of Neurobiology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham—told Atlanta Black Star that genetics is a matter of nature vs. nurture. “Nature is what you get from your parents, while nurture is how your environment shapes you as an individual,” she said, noting that an individual might have a predisposition to developing a certain condition such as bipolar disorder, schizophrenia or suicide. Lubin’s primary research is focused on investigating the molecular and genetic basis of learning, memory and its disorders.

“You can experience stress early on or later on in life,” said Lubin, who is also Co-Director of the NINDS Neuroscience Roadmap Scholar Program, whose goal is to “enhance engagement and retention of underrepresented graduate trainees in the neuroscience workforce.” “Your gene sequence changes as you age, and stress can distort that trajectory for the rest of your life,” she noted, adding that there are different types of stress, such as acute, chronic and moderate levels. And if you are exposed to chronic, unpredictable stress, that could have an impact on how you respond to your environment.

Farah D. Lubin, Ph.D., Department of Neurobiology, University of Alabama at Birmingham

“Epigenetics serves as an interface between your environmental experiences and how your DNA will be interpreted in response to those experiences,” Lubin said. “Sometimes these are extreme and destabilize you to your experiences. In cases on extreme stress, you can have long term effects. The Bible refers to generational curses and influences, and interestingly nature actually supports what The Bible says, which is, there is an effect on the molecular epigenetic information that is affected by stress that is transgenerational and passed on to your offspring.”

What are the solutions? “It is difficult because we are just beginning to understand these mechanisms and how they are triggered,” according to Dr. Lubin, noting all the complexities involved in the science of trauma. “Behavior therapy, environmental enrichment has been shown to cure a number of disorders. Exposing yourself to new, novel things is good for you, but we don’t do enough of it. In animals and humans we know enrichment helps to cure and alleviate disorders. The problem with enrichment and proper diet is that it takes more than taking a pill,” she said.

“As a science I know that diet changes your epigenetics and how you deal with stress. It helps you deal effectively and appropriately to stress. It reduces cortisol levels so you are not as fearful…I think awareness first and foremost is most important,” Lubin added, noting that Black people are beginning to take matters into their own hands. “African-American society is embracing more of who they are. You see that with women wearing their hair naturally” she said. Lubin also noted that attitudes about race are evolving among millenials, including Black young people. “But that’s not to say they do not have some of the residual effects of slavery,” she said.

In addition, Lubin says, we can learn from those who are resilient, and attempt to mimic what is present in resilient people in order to seek treatments for trauma. “There is a resilient population and a susceptible population. Whether they are disabled, have a background as slaves, suffer from the Holocaust, you can separate them into two groups. What make the resilient (bounce back) and what makes the susceptible stay stuck….The genes that encode are different in the resilient and susceptible groups.”

Interestingly, these generational effects of trauma are not believed to last forever, according to Dr. Lubin. “I believe it is six to seven generations (with 25 years a generation). Technically we are beyond these numbers, but we were re-inoculated with Jim Crow and the civil rights movement,” she offered.

“I think we as a culture need to make some major changes in the way we think about harm caused by historical trauma,” said Dr. Williams. “We now know it’s not simply ‘in the past’ but continues to influence descendants through both social and genetic (epigenetic) mechanisms. Reparations need to be meaningful and not simply symbolic to have any real impact,” she added.

Meanwhile, in a #BlackLivesMatter era, more attention is paid to the legacy of slavery and its significance in the present day. “Police have been killing and abusing our people with impunity for centuries, and now thanks to dash-cams, cell phone videos, and public outrage (Black Lives Matter), this problem is now getting the attention it deserves,” Williams said. “These images can contribute to a sense of community/cultural trauma if nothing is done, but with continued attention I think we can bring about change. These problems go back to the slavery where force of law was used to intimidate slaves and then after the Civil War to exterminate and neutralize Black males.”

Finally, Dr. Lubin responds to those who say that Black people should “get over” the trauma of slavery. “It’s a naive sentiment to say get over it, but they don’t even know what they are getting over. There are symptoms and they don’t even know why they are there. It is hard to say to a Holocaust survivor, ‘Get over it.’ They are having the same generational effect from their experiences as well.”