As America watches refugee crises in Africa, the Middle East and other parts of the world, let us not forget an inherently American and completely homegrown refugee crisis of years past — Black people fleeing slavery through the Underground Railroad. One of the Detroit stops on that Railroad — a historic Black church — has been recognized by the federal government for its role in slavery abolition and helping bring freedom to Black people escaping oppression in the South.

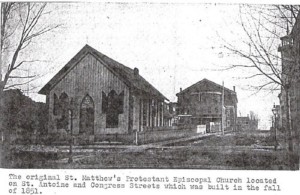

Founded in 1846, St. Matthew’s Episcopal Church is one of the oldest historically Black congregations in the U.S., and one of Detroit’s most respected and influential institutions. As Pat McCaughan of the Episcopal News Service reported, the church was recognized for its role in history when the National Park Service added St. Matthew’s to the National Network to Freedom. Even before Lincoln became a member of Congress and before Harriet Tubman escaped to freedom, this hallowed Detroit institution was helping enslaved runaways cross the Detroit River to freedom in Canada.

According to the National Park Service, during the 19th century, St. Matthew’s was a center of abolitionist activity and the Underground Railroad because of its leadership. William Lambert and Rev. William Monroe — both Underground Railroad activists and Black Detroit leaders who played a vital role in the Colored Vigilant Committee of Detroit — were involved in the church from its inception. Monroe would later emigrate to Liberia and establish an Episcopal mission there.

Further, Rev. James Theodore Holly, ordained as deacon in 1855 and priest in 1856, had encouraged free and enslaved Black people to immigrate to Canada and participate in the Underground Railroad. Rev. Holly — who became the first ordained Black bishop in the Episcopal Church when he founded the Episcopal Church in Haiti — also had worked with author and abolitionist Henry Bibb in Canada in publishing a Black anti-slavery newspaper called Voice of the Fugitive.

In addition, many of the members of the church included those who sought freedom. The population of St. Matthew’s reportedly dwindled following the passage of the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act, and the church has resided at its present location since 1971, when it merged with St. Joseph’s Episcopal Church and became known as St. Matthew’s & St. Joseph’s Episcopal Church.

“We found that it [St. Matthew’s] makes a significant contribution to the understanding of the Underground Railroad in American history … [and we] commend you on your dedication to this important aspect of our history,” said Diane Miller, national program manager of the National Network to Freedom.

This historically important center of community activism and organizing was founded above a blacksmith’s shop, nine years after Michigan became the 26th state, 13 years after Canada abolished slavery and 40 years after Michigan had abolished the practice. Over a decade, nearly 40,000 passed through Detroit under the stewardship of Lambert and other leaders. St. Matthew’s was one of three Black houses of worship in Detroit that assisted those seeking freedom during slavery.

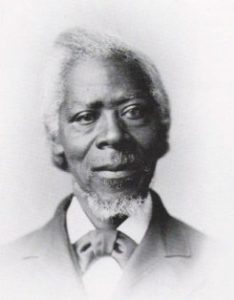

William Lambert was the senior warden and founder of St. Matthew’s.

Known as “the father of St. Matthew’s,” Lambert founded the Colored Vigilant Committee, “essentially an all-purpose organization to help freedom-seekers get to Canada,” said Roy Finkenbine, vice chair of the Michigan Freedom Trail Commission.

As McCaughan reported, Finkenbine said the organization was an illegal activity, and particularly dangerous after 1850: “It was all black in membership. They worked with select whites in the city and on the fringes of the city who would filter people to the committee. They did everything from raising funds to feeding (and) clothing people, providing medical care, hiding them in barns on the east side (and) getting them across the river late at night in skiffs hidden under the docks. They even offered legal representation.”

It was learned that for a length of time, the church did not have a building because many members had fled to Canada or to California to evade arrest or kidnapping. The Fugitive Slave Act was a federal law that provided for the capture and return of escaped slaves, with harsh punishment meted out for the slaves and those who aided them. One byproduct of the enforcement of the law was that free Black people were often captured and enslaved.

“We hold our liberty more dearly than we do our lives, and we will organize and prepare ourselves with determination: live or die, sink or swim, we will never be taken back into slavery,” Lambert once said. “We will never voluntarily separate ourselves from the slave population in the country, for they are our fathers and mothers, and sisters and brothers; their interest, their wrongs and their sufferings are ours. The injuries inflicted on them are alike inflicted on us. Therefore, it is our duty to aid and assist them in their attempts to obtain their liberty.”

Clergy and congregants of St. Matthew’s and St. Joseph’s Episcopal Church

Among the other notable facts regarding St. Matthew’s past was that the Detroit chapter of the NAACP was founded at the church and met there. Further, in the 1920s the church established a relationship with Henry Ford and facilitated the hiring of Blacks by the automaker during the Great Migration of African-American refugees from the Jim Crow South. And in 1926, Marian Anderson performed her first Detroit concert at the dedication of a new parish house at St. Matthew’s, and she returned in 1939 for a repeat performance after she was barred from Constitution Hall by the Daughters of the American Revolution.

“St. Matthew’s stands in the great tradition of our historically Black churches, many of whom were born out of the struggle for racial justice,” said Annette Buchanan, national president of the Union of Black Episcopalians. “The Black Episcopal Church has been and will continue to be the conscience of our denomination reminding us of our baptismal covenant to respect the dignity of every human being.”

Although many of the institutional symbols of Black resistance and organizing against oppression have been long turned into dust, St. Matthew’s remains a bridge to the past, lest we forget the struggles of the Black church to make people free.