The health disparities between people of color and whites are well documented, with Blacks having a higher risk for a multitude of diseases, including heart disease, diabetes, hypertension, strokes and cancer. But a new study, which finds that Blacks and Latinos have to wait far longer to see a doctor, helps place these alarming disparities into their proper context.

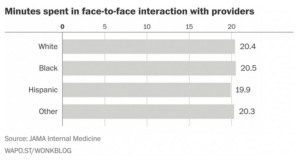

The study, which was released in JAMA Internal Medicine, found that Black, Brown, less educated and unemployed people waited 25 percent longer to see a healthcare professional. While white patients waited 80 minutes to see a doctor, Blacks waited 99 minutes, Latinos waited 105 minutes, and other nonwhites waited 83 minutes. However, those groups who wait longer in terms of “clinic time” are not receiving more time with the doctor.

The study is a part of growing evidence that racial health disparities are not due only to lifestyle and other social factors such as economic status and zip code, but to actual racism in the healthcare system. The authors of the study identify timeliness of care as an important aspect of quality.

“Racial and socioeconomic disparities exist in receipt of timely appointments and interventions. Patient time burden (i.e., time spent traveling to, waiting for, and receiving ambulatory medical care) is a separate domain of timeliness,” the report read. “Disparities in this domain have received less attention, although prior work has described inequalities in pediatric emergency

The report notes that some of the difference in wait times may be explained by the kinds of clinics in which patients seek care.

“It does not change the underlying implications that disparities in timeliness to obtaining care exist for more vulnerable patient populations,” wrote the editors of the journal. “This study characterizes a problem we all know to exist.”

“It could be bias, conscious or unconscious, on the part of providers, or other staff that work at the site where they’re receiving care,” Alexander Green, associate director of the Disparities Solution Center at Massachusetts General Hospital, told the Washington Post.

Green once conducted a test on unconscious bias among physicians, in which he learned that when doctors believed Black people were less cooperative, they were less likely to recommend aggressive treatment for chest pains.

Racial bias in the medical profession has its impact on children as well. For example, JAMA Pediatrics released a study which determined that among children diagnosed with appendicitis, Black children were less likely to receive pain medication than white children, including narcotic derived opioids such as morphine and Percocet for severe pain, or any pain medication at all for moderate pain, even Tylenol. The authors noted that “significant disparities remain in our approach to pain management among different populations.”

Meanwhile, in an editorial included with the findings, physicians wrote “we are left with the notion that subtle biases, implicit and explicit, conscious and unconscious, influence the clinician’s judgment.” These findings remind us of the troubling history of medical experimentation on Black people in this country, including, but by no means limited, to the Tuskegee syphilis experiment.

In contrast, another recent study of patients at U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs hospitals found that when Blacks and whites receive exactly the same care and treatment, Blacks fare better than whites. In the study of 3.1 million patients in the VA system, the mortality rate for Black men was 22.5 per 1,000, as opposed to 31.9 per 1,000 for white men. Further, Black men and women in the analysis were 37 percent less likely than whites to develop heart disease, the leading cause of death in America. The rate of strokes was identical across racial lines. However, among the general population, a data analysis from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey found that the mortality rate for Blacks was 42 percent higher than for whites.