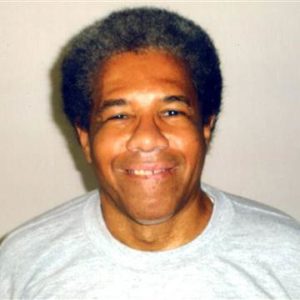

The story of Albert Woodfox tells us all that we need to know about the horrific conditions facing prisoners in the United States, and the troubling origins of American mass incarceration rooted in slavery.

Calling it “the only just remedy,” federal district Judge James Brady ordered Woodfox, 68, released immediately and unconditionally from the Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola, after spending 43 years in solitary confinement. The court ruled that based on evidence pointing to his innocence, Woodfox should not be tried a third time for the 1972 murder of a prison guard.

Woodfox is the last of the Angola 3, who were convicted of the killing of the guard during a 1972 prison riot. At that time, the men were organizing a chapter of the Black Panther Party, and Woodfox always maintained his innocence, claiming the prison retaliated against him for his political organizing. He was originally behind bars in connection with an armed robbery conviction.

In November, a federal appeals court overturned Woodfox’s conviction, but the state charged him again in February. In response to an appeal of Woodfox’s release from Louisiana Attorney General Buddy Caldwell, the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals issued an emergency stay delaying freedom for the longtime inmate.

There are two other stories behind the case of Woodfox, in addition to the actual circumstances that have kept him unjustly imprisoned for the past four decades. The first is the story behind the human rights violation known as solitary confinement, which is a form of torture. The second, perhaps more relevant issue, is that Angola prison is a former slave plantation that acts as a modern-day slave plantation.

Also known as isolation, restricted housing, maximum security, supermax, administrative segregation, punitive segregation, permanent lockdown or simply ‘the hole,’ solitary confinement is considered inhumane and a form of torture by international standards after only a few days or weeks. Yet in the land of the free, people spend years and decades in these dungeons and torture chambers.

Typically, an inmate spends 22 hours a day in a narrow cell the size of a parking space, with no human interaction and absolutely nothing to do. This is where the individual must sleep, eat and relieve himself or herself. According to the U.S. Department of Justice, 80,000 prisoners across the nation are held under such conditions.

The UN Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment—also known as the Torture Convention—aims to prevent torture and other acts of cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment around the world. The UN defines torture as “any act by which severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted on a person for such purposes as obtaining from him or a third person information or a confession, punishing him for an act he or a third person has committed or is suspected of having committed, or intimidating or coercing him or a third person, or for any reason based on discrimination of any kind, when such pain or suffering is inflicted by or at the instigation of or with the consent or acquiescence of a public official or other person acting in an official capacity. It does not include pain or suffering arising only from, inherent in or incidental to lawful sanctions.”

Parties to this convention, including the U.S., must ensure torture is a criminal offense, prevent torture and review interrogation rules and practices, train and educate officials on the issue, and investigate torture allegations.

Juan E. Méndez, the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture, called for an international ban on solitary confinement except in rare circumstances, with a definite prohibition for juveniles and those with mental disabilities, and an absolutely prohibition over 15 days—the limit after which irreversible harmful psychological effects can occur. However, many prisoners in the United States have been kept in isolation for decades. And no one in America has been there longer than Woodfox.

According to the American Friends Service Committee, a 2006 investigation found as many as 64 percent of people in the hole were mentally ill. Due to the lasting mental damage caused by prolonged isolation, including depression, anxiety and psychosis, solitary is a harsh measure contrary to rehabilitation— which should be the aim of the penitentiary system.

Utilized as a punishment for infractions both violent and minor, and often used as a tool of repression against jailhouse lawyers and political prisoners, solitary confinement violates the Eighth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, and was a factor behind the 2011 hunger strikes in the California prison system.

Meanwhile, Angola prison—which at 28 square miles is the largest maximum security institution in the country—is a former slave plantation that still functions as one. The prisoners, overwhelmingly Black men, work in the fields picking cotton, corn, wheat and soybeans, while the white guards who live on site, known as freemen, roam the fields on horseback, shotgun in hand. Indeed, this is taking place in the twenty-first century. Angola is a prime example of the connection between the criminalization of Black people during slavery and America’s modern-day racialized prison system.

Just as the racially-skewed criminal justice policies have led to the incarceration of Black, Brown and poor people, these dynamics operate on overdrive in Louisiana. In a perverse way, it is fitting that a fully operational slave plantation would call Louisiana home.

As Nola.com reported in 2012, Louisiana is the world’s prison capital—the state with the highest incarceration rate in a nation that has the most prisoners of any developed country in the world. One in 86 adults in Louisiana is on lockdown, including 1 in 14 Black men. Moreover, 1 in 7 Black men is in prison, on parole or on probation. A guilty vote from 10 of 12 jurors, or three drug convictions can land a defendant in prison for life without parole. Sheriffs lobby lawmakers to keep the sentences high and the beds full. Most inmates are housed in for-profit facilities, and are traded like livestock, a throwback to the Jim Crow convict lease system.

So when we look at Woodfox and wonder how he endured all of those years in the gulag, under circumstances we cannot comprehend, we must remember that slavery is not merely a relic of the past. Slavery is taking place at Angola today.